Not your average Mardi Gras. Malta’s pre-Lenten Carnival emphasizes history and culture over skin and pulchritude. But revelers dressed as Queen Victoria and her court have a grand time nonetheless.

The music is upbeat; the busy streets are overflowing with garishly costumed revelers. Nearby, a giant Sean Connery is playing the bagpipes, while beside him Mr. Bean is rolling his eyes.

No, this is not impending insanity. It’s Carnival, Malta’s version of Mardi Gras.

For five whole days, the capital city, Valletta, turns into Party Central, and virtually the entire population – children included – dons elaborate costumes and takes to the streets. Some are parading in colorful, outlandish versions of the traditional dress of Japan, China, or India. Queen Victoria and Marie Antoinette, both richly clad in magnificent ball gowns, pose for eager photographers. And one group of children is sporting scarlet British Beefeater regalia, each with a large Big Ben tower sprouting behind them like a permanent selfie backdrop.

Extraordinary floats feature characters both familiar and fantastical, most with expansively moving parts. A tribute to Alice in Wonderland is delightfully grotesque. And on the back of Mr. Bean’s float, a giant Tom Jones clutches his microphone.

To cap it all off, the night sky is alive with fireworks.

It’s hard to believe this astonishing revelry heralds the start of Lent, one of the most solemn holidays in the Christian calendar. But that is the point after all, isn’t it? And Malta loves to party.

In this predominantly Catholic country, with so many feast days, saint’s days, and holidays, there are plenty of excuses to party. Indeed, the fact that Malta as an independent country exists at all is incentive enough for celebration.

Malta’s Carnival is for both young and old. These children celebrate the years of British occupation

Malta may appear an insignificant dot on the map that few people in Asia or the Americas can locate. But sited in the narrow sea lane between Italy and the North African coast it has always been of strategic significance and holding it was the key to naval dominance in the Western Mediterranean.

In fact, that insignificant dot was the most bombed country during World War II, as the Germans desperately tried to gain a stronghold here. And historian Julian Humphrys (BBC History Revealed) has suggested that for Suleyman the Magnificent, leader of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, Malta was the first step in his plan to ultimately rule Europe. Neither Suleiman nor the Germans succeeded.

Others did. This mini-archipelago of three small islands – Malta, Gozo and Comino –has been invaded again and again. Over the centuries, Phoenicians, Romans, Ottomans, Normans, Spanish, French, British, and more have had a crack at conquering it, some more successfully than others.

What is truly intriguing is that each ruling nation left a little of themselves behind, adding to the extraordinary cultural blend that is modern Malta. Indeed, my stay here became a mini scavenger hunt as I looked for traces of these roots.

In the beginning…

Seven thousand years ago, these three islands were occupied by some of Europe’s earliest peoples. Remnants of megalithic constructions offer a glimpse into these Stone Age human communities. Known only as the Temple Builders, they left behind enormous stone structures, like the impressive Tarxien Temples on the island of Malta or the huge Ġgantija complex on Gozo. Erected about a thousand years before the pyramids of Giza in Egypt, some of Malta’s temples are believed to be the oldest free-standing monuments in the world.

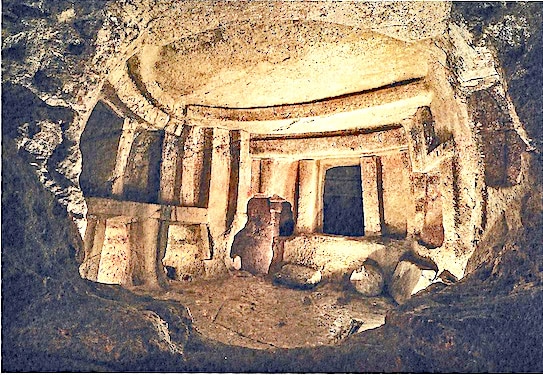

One of the most remarkable Neolithic sites is the Hypogeum at Ħal Saflieni. This series of caves, carved deep underground into soft limestone, is one of the oldest known burial places in the world. The remains of some 7,000 individuals were found in the burial holes, and for more than 5,000 years, they remained undisturbed.

Cool, dark and more than a bit spooky, the Neolithic tombs inside the Hypogeum at Ħal Saflieni held 7,000 souls for more than 5,000 years. Now it shelters a steady, if small, stream of tourists who must reserve space far in advance.

Descending into the cool, dark depths of this sacred site, I can’t help but be awed at a civilization whose simple tools excavated and sculpted these large, underground chambers with neatly squared posts. Carved niches once held sacred objects, and on the walls, I can barely discern faint red ochre spirals and triangles. What did these symbolize? Archaeologists suggest that this was probably a religious sanctuary as well as a burial ground.

Ħal Saflieni was only discovered in 1902. Today, to protect the site from the carbon dioxide we exhale, only 10 visitors are allowed to enter every hour – sans cell phone or any photographic equipment. Needless to say, bookings to get on the visitor’s list are taken months in advance.

The Temple Builders left no recorded history, and sadly, many of their structures have deteriorated, and even been destroyed in misguided attempts to modernize the country. In drawings at Ġgantija’s museum, I could see how this complex looked in the 19th century, before some of the ruins were removed. Standing at the edge of the Xagħra plateau, facing toward the equinox sunrise, Ġgantija encompasses two temples, their curving walls composed of enormous, carefully stacked stones. It seems inconceivable to me that 5,500 years ago, these early peoples carved, moved and raised these enormous stones. After all, they had no metal tools or even a wheel!

One of the Tarxien Temples, Mnajdra is a UNESCO World Heritage site

Much more history might have been lost in the name of modernization, but in 1915, Sir Temi Zammit, a visionary Maltese archaeologist, took matters in hand. Over the next 20 years, he undertook the study and protection of sites all over the country, completing the excavation of the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum as well as other archaeological treasures like the megalithic Tarxien Temples, Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra. All of these are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. And through his efforts we know a little more about the peoples who predated recorded history.

Modern invaders

It isn’t until 800 BCE, when the Phoenicians invaded, that Malta’s history begins to be written down. These seafaring traders, who busily plied Mediterranean waters, occupied what is now Lebanon. Their greatest contribution was their alphabet, which is considered to be the ancestor of almost all modern alphabets. But my scavenger hunt turned up another legacy – a pair of watching eyes painted on the prows of many colorful Maltese fishing boats. These ‘eyes of Osiris’, originally borrowed from the Egyptians, are said to provide good health, and to protect fishermen while at sea.

In 218 BCE, Malta became part of the Roman province of Sicily. Temples and statues from this period indicate that the Maltese adopted Roman gods. In the town of Rabat, I wandered through the remains of a Roman era villa, a historic site that dates to a time when Roman armies ruled large swathes of Europe. Elaborate mosaic floors, wall plaster painted to represent colored marble, and numerous excavated artifacts are remarkably well preserved.

Nearby are the catacombs in which St. Paul is said to have sought refuge when he was shipwrecked in 60 AD, en route to Rome to be tried as a political rebel. With the saint came possibly the most important and enduring legacy of Malta’s many visitors – Christianity was introduced with obvious success.

Invaders from North Africa brought distinctive Islamic art and architecture. Mdina was made their capital city. Today, this magnificent walled city of narrow roads and elegant courtyards is famous for intricate filigreed silver as well as striking glass creations, both of which have become a must for souvenir hunters.

Inside the old walled city of Mdina the narrow streets and elegant courtyards evoke the architecture of North Africa

North Africans introduced flatbreads and the flaky pastry which is the basis for Malta’s favorite fast food – pastizzi, a pastry turnover stuffed with either ricotta cheese or savory split peas. Indeed, the best pastizzi is reputed to be found at Is-Serkin just outside the walls of Mdina. Based on the dozen or so different pastizzi I sampled during my stay, I’d have to concur.

The Norman conquest of Malta and Sicily in 1090 once more linked these two island nations in a lasting friendship. The Maltese, wisely I believe, chose to adopt some of the best elements of Sicilian cuisine and these remain to this day – arrancini (rice balls), cannoli (ricotta filled pastry), caponata (tomato, pepper and olive appetizer), and rabbit stew. I had my first taste of rabbit at Il-Malti, a restaurant in Sliema, a short ferry ride from Valetta. While I tried other versions, this first experience of Malta’s national dish remained my favorite.

The Normans brought their own zeal for construction. As they did all over Europe, they added magnificent castles, forts and watch towers to the landscape. One of the most unique is the watch tower in Birgu, across the water from Valletta, which has a giant eye carved on one side and a giant ear on the other – a clear message to those guarding the city to remain vigilant, and a warning to those who would attack.

Maltese boats protected by the Eyes of Osiris anchor alongside the quay in Birgu across the bay from Valletta.

Two hundred years later, it was Spain’s turn in Malta. They left two noteworthy gifts. The first, the guitar, is still popular with Maltese folk musicians. But the second has become a common feature of Maltese architecture – gallerijas. These colorful, enclosed balconies are typically found in Aragon. Once ubiquitous, many gallerijas have been torn down as houses have given way to apartment complexes. But the Maltese government is now taking steps to prevent these unique architectural features from being lost.

The Order of the Knights of St. John probably had the most significant influence on Malta. This military religious order was established during the Crusades under its own Papal charter, and built a stronghold in the Holy Land. Some 400 years later, Sultan Suleiman drove them out of Jerusalem and the Middle East. In 1530, with nowhere for the Knights to go, Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, gave them the island of Malta.

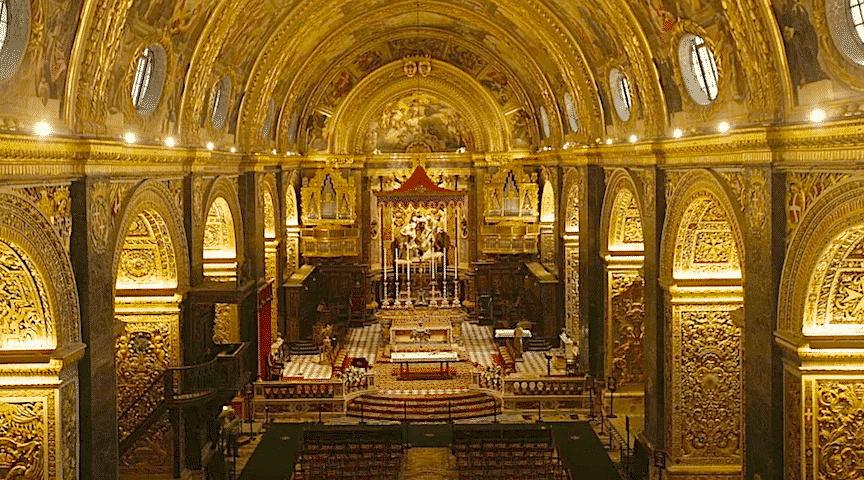

They became known as the Knights of Malta. Their distinctive six-pointed cross remains the symbol of the country, and their Grand Masters – head honchos of the order – are buried in magnificent marble tombs in St. John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta.

Built by the Normans, the Watch Tower of Birgu is adorned with a giant eye on one side and an ear on the other, a reminder that people inhabiting an island nation must be ever vigilant since attack can come from all sides

Belying its simple white exterior, the interior of St. John’s is opulent in the extreme, with barely a square foot of wall, ceiling or floor undecorated with murals, statuary, marble tombs and gold, most of it dedicated to the Knights of Malta. “Actually, the plain exterior saved this church from the Nazis who thought destroying it would demoralize our country,” said Carmen Grech, a guide at the cathedral. “But they thought this ordinary white building couldn’t be a cathedral, so they bombed a nearby church which was more beautiful and grand.”

St. John’s Co-Cathedral is high on my must-see list, and not simply for its ornate interior. I’m here to view two paintings by Caravaggio on display in the oratory – St. Jerome, and The Beheading of John the Baptist. Wanted for murder in Italy, the Knights gave the artist refuge; in exchange he painted these masterpieces. The latter is considered the artist’s magnum opus and is the only one he signed – Caravaggio is scrawled somewhat ghoulishly in one of the only spots of color, the bright red blood flowing from The Baptist’s neck.

St John’s Co-Cathedral was commissioned in 1572 to serve as the church for the Order of the Knights of St John. It was completed in 1577 and dedicated to St John the Baptist, one of the two patron saints of the Order. The Cathedral consists of nine elegantly decorated chapels on either side; eight were constructed for each of the langues of the Knights of St John, and the ninth is dedicated to their patron saint, Our Lady of Philermos.

But Suleyman the Magnificent wasn’t done with the Knights of Malta. The Ottoman ruler’s success in the Holy Land emboldened him to take them on in their new home. The Great Siege of 1565 proved to be Malta’s proudest moment. Some 2,000 foot soldiers of the Knights of Malta and 400 Maltese men, women and children actually repelled the might of the great Ottoman Empire. “Historians say that if the Ottoman Empire had succeeded in taking Malta, Europe as we know it today would not exist,” explains Grech. “This is why we celebrate the victory on September 8 each year.”

The French invaded next, but Napoleon Bonaparte himself stayed just six days, en route to Egypt. By the time he left he must have been heartily despised; he departed with his ship loaded with looted gold, silver, paintings and tapestries. Is it significant that the Maltese greeting of Bonġu (pronounced bonne zhoo) probably originates with Bonjour, but the fond French farewell, au revoir (‘til we meet again) didn’t make it into the Maltese vocabulary? By the way, most of Napoleon’s booty actually ended up underwater, when his ships were sunk by the British Navy under Admiral Nelson, at the 1798 Battle of the Nile.

The last goodbye

The British were the last country to occupy Malta; granting the islands independence in 1964. The people of Malta wisely eschew British cuisine, whose main contribution here appears to be the classic breakfast ‘fry-up’ of bacon, sausages, eggs, mushrooms, baked beans, grilled tomatoes. Nonetheless, the British heritage is strong: England’s classic red post boxes and telephone booths; cars drive on the left hand side of the road; and a Westminster-style parliamentary structure.

English is widely spoken and understood, but the official language of Malta is Maltese, whose roots are Semitic. Many places in Malta – Marsaxlokk (pronounced Mar-sa-schlock), Birzebbuga, and Ħaġar Qim – owe their tongue-twisting names to those Semitic roots. Although it is the only Semitic language written using an alphabet based on Latin script, visitors find the spelling and pronunciation of Maltese words a challenge. For example, the Maltese for ‘please’ is ‘jekk jogħġbok’.

More than history

If exploring Malta’s history and cultural roots aren’t incentive enough to visit, this small country boasts spectacular scenery and beautiful beaches. Swimming and snorkeling at the aptly named Blue Lagoon, off the island of Comino, is heralded as some of the best in Europe. And a boat ride through the Blue Grotto, a short bus ride from Valletta, offers stunning landscapes of limestone cliffs and water that seems to change from blue to green and even pink.

After visiting Malta’s churches and archaeological sites, take a boat ride through the Blue Grotto just outside Valletta

Getting around is easy; Malta is just 27 kilometers long and 14 kilometers wide. We used the efficient bus system as our means of transportation for two reasons. First it’s inexpensive – one can get from one end of the island to the other for two Euros. But more importantly, they may drive on the left like the British, but the Maltese approach maneuvering through traffic like their traditional friends, the Italians. My nerve failed me at the thought of self-drive options.

I did, however, pluck up enough courage to try Rolling Geeks, quirky little self-drive electric cars. Because these come with pre-programmed GPS that takes you on the perfect tour, one didn’t need to figure out signs and directions.

While Malta is becoming a popular destination, it’s still relatively undiscovered, and relatively cheap by European standards. The people are friendly, and the cuisine one of the most underappreciated in Europe. The adventure of searching for clues to Malta’s remarkable collection of cultural roots is just a delightful bonus.

Liz Campbell arrived in Toronto, Canada via Burma (now Myanmar), India, and England. She has been a freelance travel and food writer for more than 20 years with stories published in The Globe & Mail, Zoomer, Foodservice & Hospitality magazine and more.