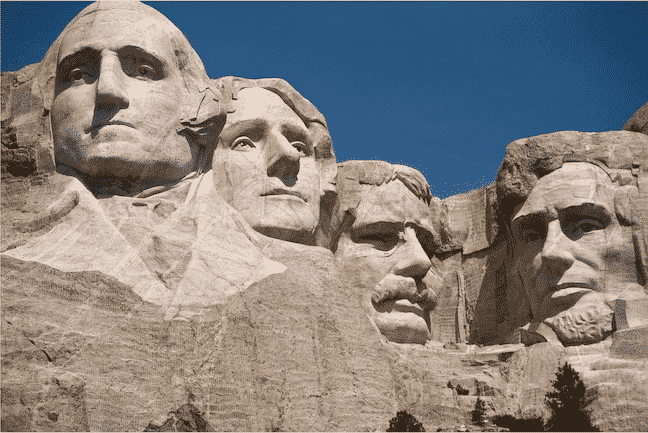

Four of our greatest presidents. Or two slave owners, a racist and an Indian killer? Will a Minnesota beat cop’s act of brutality change America’s perception of its past?

By Mark Orwoll

There are countless paths across America. I’ve followed many of them.

Route 66, with its tepee motels, trading posts, and homey cafés. The Lincoln Highway, a hodgepodge of interconnected surface streets stretching from New York’s Times Square to Lincoln Park in San Francisco. The lonely northern route along Interstate 90, where distances are so great that the Burma Shave-style road signs offering “Free Ice Water” at Wall Drug Store lend a Holy Grail-like aura to the never-ending drive across South Dakota’s badlands. I’ve long wanted to take a cross-country trip through the southern reaches of the USA and I finally found an ideal route. Unfortunately, I can’t take that path now. Why?

Because the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway no longer exists as a transcontinental motorway.

The route, named for the President of the Confederate States of America, once stretched from Arlington, Virginia, to San Diego, and then north to Washington State. How is it that, at this mature stage of my life, I’d never even heard of it?

According to the Federal Highway Administration, the Jeff Davis Highway was one of 250 auto routes devised by motor clubs and civic organizations in the 1910s and ’20s. Among them were the Yellowstone Trail, the Dixie Highway and the National Old Trails Road. The Davis Highway, conceived in 1913 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, was in direct response to the creation earlier that year of the northerly Lincoln Highway. Later, in 1925, the government stepped in and created the federal interstate system of numbered routes. The old, unofficial “highways” remained, but largely as inefficient though charming remnants of the pioneering days of motoring.

Some of the Davis roadside signs still stand, including along U.S. 1 in Virginia and, ironically, U.S. 80 from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, the route followed by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., during his celebrated march for voting rights. Other signage has been removed by state and local governments. In August 2017, the mayor of San Diego ordered the removal of yet another Davis Highway marker in front of Horton Plaza, in the heart of the city’s downtown. New Mexico removed three Davis Highway markers in 2018. In June 2020, an 800-pound Davis Highway marker, originally located on Highway 99 in Bakersfield, California, was relocated to “a weedy outdoor storage area” behind the Kern County Museum. A highway marker on U.S. 60 east of Mesa, Arizona, was removed in July and returned to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, at their request, because of repeated vandalism.

The Davis Highway is only one of many memorials—including statues, schools, public buildings, monuments, and military bases—to fall under the harsh light of historical re-examination following the heightened racial sensitivity of the past year. A good thing? A bad thing? That’s not the point. The cultural—and physical—landscape is mutating, and this summer’s travelers are apt to be among the first to notice the alterations.

The changes afoot are not limited to the United States. Anti-colonialism was the spur that drove many nations to change their names. Burma became Myanmar following a military coup in 1989. Siam became Thailand in 1939 during the rule of a nationalist dictator. Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge changed its name to Kampuchea in 1976 only to become Cambodia again in 1990. Similarly, in a cultural rebellion against Africa’s imperial past, Southern Rhodesia changed its name to Zimbabwe, Northern Rhodesia switched to Zambia, Spanish Sahara rebranded as Western Sahara, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan pared down its name to Sudan, British East Africa morphed into Kenya, and the Belgian Congo proclaimed itself the Republic of Zaire before finally settling on the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The politicization of cultural history and monuments is especially strong in Western Europe. Take the pre-Lenten Carnival in Aalst, Belgium, which received a UNESCO Intangible World Heritage designation in 2011, only to have the recognition rescinded because of anti-Semitic stereotypes appearing in many of the displays. Nearby Antwerp removed a statue of King Leopold II in June 2020 because Leopold’s regime was responsible for the death of millions of Africans during the colonization of the Congo. A statue of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in London’s Parliament Square may have to be relocated for safekeeping from vandals who claim he held white-supremacist views. In Africa, students at the University of Ghana toppled a statue of Mohandas Gandhi because he once said Indians were “infinitely superior” to Blacks.

The phenomenon is international in scope but primarily focused in the U.S., where the reassessment of historical and cultural iconography reached a crescendo in the wake of the May 2020 killing of George Floyd, a Black man arrested by police in Minneapolis for passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill at a convenience store. After being pinned to the ground by a policeman’s knee to his neck, Floyd died. His final words, “I can’t breathe,” quickly became a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement during which protestors sought out emblems of racial injustice and, in many cases, tore them down. The cop’s subsequent conviction of murder has not lessened the anger or given them confidence in American justice.

Many objectionable symbols and names might seem obvious, others less so, and some completely innocent. But look deeply enough into any historical figure and you’re apt to find something unpleasant. Last year, the San Francisco Board of Education established a committee to decide if the people schools were named for held racist views. Among those targeted for cancellation: Paul Revere, Robert Louis Stevenson, Father Junipero Serra (founder of California’s Franciscan missions), John Muir, Abraham Lincoln and George Washington. Also on the deplorable list were schools named Mission, Presidio and Alamo. Only recently was the renaming effort curtailed after it became a municipal embarrassment.

Canonized in 2015 by the Vatican, Junipero Serra was an 18th century Franciscan priest who built nine missions throughout California. Since the death of George Floyd, statues of the prelate, many close to missions he helped build, have been defaced or torn down. There is no evidence he ever committed a murder.

I was assigned to write a story on this overarching topic, specifically as it pertains to travel, by my editor at the East-West News Service. His brief to me emphasized the loss of American monuments, often in misguided attempts to identify perpetrators of racism. But he placed no restraints on what I should or should not include in my report. In a bid for some clarity and focus, I did as many writers do: I asked another writer for her opinion.

Jacqueline Swartz is a long-time writer and native Californian. She closely followed the cancellation controversy in her hometown where her alma mater, Lincoln High, was among the schools up for renaming.

“I think you have three basic ways to approach this subject, based on how every city and state has decided to deal with the issue,” she suggested during a recent phone call. “Leave it, tear it down, or truth and reconciliation.”

Leave It

Auschwitz concentration camp is an emblem of racism and anti-Semitism in southern Poland. Nazi Germany used the camp to round up—and execute—more than a million Jews, gays, Roma (Gypsies) and other “undesirables” during World War II. But when the war ended, Auschwitz and other concentration camps (including Dachau and Buchenwald) were left standing. To this day, you can visit Auschwitz and other death camps despite the preference of many people to raze them and extinguish the emotional pain of their physical presence.

Ernst Michel’s view was exactly the opposite. Michel was held in Auschwitz for two years for the “crime” of being a Jew. But after the war, he fought to preserve the concentration camp exactly as it was at the time.

“This is the reason why I believe whatever happens in Auschwitz, it should be kept the way it is,” Michel told ABC News in 2006. “I will want to be sure that the story of what happened to us in the middle of the twentieth century will not be forgotten. So that the hundreds of thousands of visitors, who are coming from all over the world, will see what happened — in this place, in our time.”

A more nuanced and sometimes lengthy consideration process has allowed other disputed monuments to remain intact while their future is being decided. Stone Mountain, for example, sixteen miles east of Atlanta, features a massive mountainside bas-relief artwork of Confederate icons Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. Begun in 1916 and completed in 1972, the attraction is the centerpiece of the 3,200-acre Stone Mountain Park, overseen by the quasi-governmental Stone Mountain Memorial Association (SMMA). The day-to-day operations feature a scenic train ride, an aerial tram, campgrounds, hotels, and seasonal events. Today Stone Mountain Park attracts some four million visitors a year, making it Georgia’s No. 1 tourist attraction. But its family-fun amusements can’t disguise the reason it was created: SMMA’s legislative mandate is to maintain the park as a memorial to the Confederacy.

Stone Mountain is Georgia’s leading tourist attraction. Created initially as a memorial to the Confederacy, the amusement park also contains hiking trails, a golf course, camping grounds and an aerial tramway. Photo by Paul Brennan from Pixabay.

In light of Black Lives Matter, SMMA must grapple with the changing times. Its board of directors has “a contemporary understanding of the park,” says Mark Jaronski, deputy commissioner of Explore Georgia, the state’s tourism office. “Their aim is to be inclusive, not exclusive. The park needs to be positioned to meet the needs of the twenty-first century.”

Meantime, other Georgia Confederate accolades also remain in place—roadside markers, statues, historic houses, and the like. Many of them are under the purview of private organizations or municipalities. Not that it would make a difference if they were under state ownership, because Georgia law prohibits the removal of any monument related to war and the United States, including the Confederate States of America, whether on state property or not.

Well, sure, might be the response. That’s Georgia! Of course they’re going to protect markers that some might perceive as racist. But if you think such views are limited to Dixie, hop on the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway (or what’s left of it) and head west for 2,200 miles to John Wayne International Airport in Santa Ana, California. The transit hub was renamed for Wayne in 1979 to honor the actor’s status as a symbol of American exceptionalism and his long-term residency in nearby Newport Beach. Today, the airport bears not only Wayne’s name but a larger-than-life statue of the actor in Western garb. Despite calls to remove the statue and rename the airport because of Wayne’s purported white supremacist views, the Orange County Board of Supervisors has resisted making any changes. But as the conservative bastion becomes more liberal, that may change.

Perhaps the most obvious example of a contentious monument that remains standing despite calls for its removal is Mount Rushmore National Memorial, whose sculpted faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt are as entwined with American iconography as the U.S. Capitol dome and the Statue of Liberty. But many want to tear it down.

Justifications to destroy the monument include its location on sacred Indian lands, sculptor Gutzon Borglum’s ties to white supremacists, Lincoln’s authorization to execute thirty-eight Dakota (Sioux) warriors, Roosevelt’s anti-Indian statements, and the slave ownership of both Washington and Jefferson. The most unexpected protest comes from Kimberly Ford, a great-granddaughter of Borglum. “I believe it is time,” she wrote in a July 2020 op-ed in USA Today. “Time to remove a monument that celebrates the perpetrators of a genocide, a monument that sits on the sacred land of the very people who continue to be so deeply wronged today.”

Tear It Down

Most veteran travelers would agree that they would rather experience a controversial attraction firsthand than be told, “They tore it down yesterday before you got here.” The world, however, doesn’t revolve around recreational travel and culturally curious visitors, so monuments are being removed at a furious pace.

The first monuments to fall in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement were the easy targets—mainly statues in public squares. Throw a heavy rope around one, get twenty or thirty of your best friends to join in, and yank until the artwork comes crashing down.

The list of such monuments destroyed by protestors in 2020 would double the length of this article, but a few highlights include the Robert E. Lee statue at Robert E. Lee High School in Montgomery, Alabama; the North Carolina Confederate Monument in Raleigh, North Carolina; a Confederate soldier’s grave marker in Silver Spring, Maryland; statues of Father Junipero Serra in San Francisco, Sacramento, and Los Angeles; and statues of Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln in Portland, Oregon.

Travelers aren’t apt to plan a vacation around seeing a statue in some out-of-the-way traffic intersection or pocket park. But what about destinations whose monuments are fundamental to their history and, in many cases, an essential part of their tourism outreach? Many of those monuments are being removed – voluntarily or under pressure – by the municipalities and organizations that own them.

For a time I lived on West 77th Street in Manhattan, just off Central Park and directly across from the Museum of Natural History. As I would leave my apartment building every morning on my way to the subway, I would pass by a dramatic statue near the museum’s main entrance. The Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt features the twenty-sixth president on horseback, flanked by a robed Indian chieftain on one side and a near-naked Black man on the other, the latter two both on foot. It’s an impressive statue and a well-meant tribute to Roosevelt’s contributions to natural history.

But the Roosevelt statue’s elements of racial hierarchy led a New York City commission in 2017 to determine that the statue could remain only if more information was provided to add historical context. A museum project devoted to that goal was ongoing…until June 2020. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, the museum decided that the statue should be removed entirely.

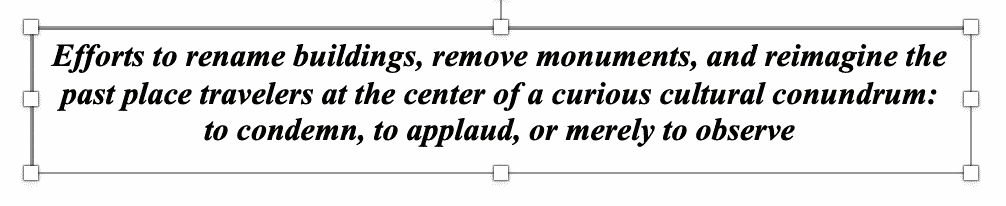

Confedrate General J.E.B. Stuart no longer commands an intersection on Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA.

Richmond, Virginia has long touted its Monument Avenue as one of the highlights of any visit to the former Confederate capital. The august boulevard featured outsize statues and enormous supporting plinths of Lee, Davis, Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, Matthew Fontaine Maury, and, in an effort toward equality, Black tennis star Arthur Ashe. The statues were all erected in grand style at various points along the avenue from 1890 to 1929 (the Ashe statue was added in 1996). Elegant homes swiftly lined the thoroughfare, making it one of the city’s most sought-after neighborhoods. Celebrated in souvenir postcards and tourism brochures, Monument Avenue became an iconic Richmond attraction. The American Planning Association in 2007 named it one of the Ten Great Streets in America.

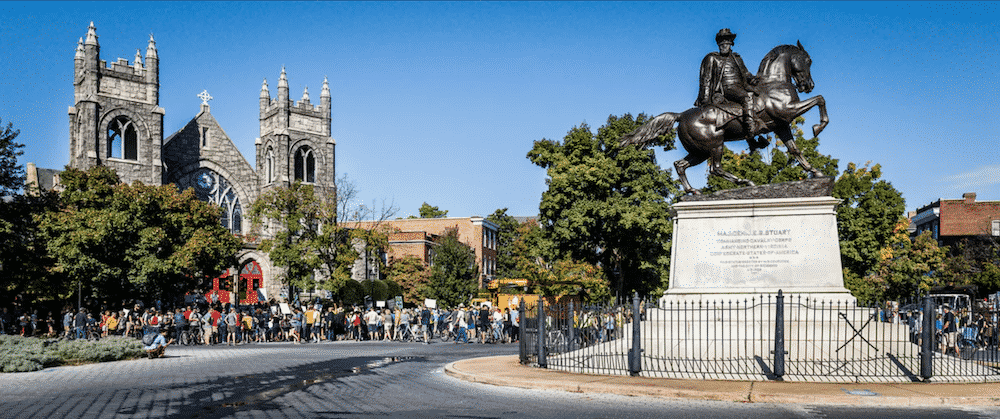

But things change. Following the 2020 protests over George Floyd’s death, Richmond officials removed the statues of Stuart, Jackson, Maury, and Davis (the last was toppled by protestors), but kept those of Lee (currently the subject of a lawsuit by those who wish to preserve it) and Ashe.

Similarly, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu ordered the removal of four prominent Confederate statues in the spring of 2017—Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, Jefferson Davis, and The Battle of Liberty Place. Even though I’m a dyed-in-the-wool liberal Yankee, it troubles me to think that those monuments are no longer there.

The list of monuments that have been removed preemptively by their owners is even longer than the roster of those that have been forcibly taken down by protestors. A few examples include a slave whipping post in Georgetown, Delaware; a memorial honoring a meal given to Confederate soldiers by residents of McConnellsburg, Pennsylvania; a monument to Confederate General Albert G. Jenkins in Hampden Township, Pennsylvania; a memorial to Confederate troops in Phoenix; busts honoring Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson at Bronx Community College, New York; the Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument in Indianapolis; the Confederate Memorial Fountain in Helena, Montana; and the Montgomery County Confederate Soldiers Monument in Dickerson, Maryland.

The next question surely must be, wait, what?! Confederate statues in Union states?! They all have intriguing stories to tell–stories that, for now, are incomplete.

The list of voluntary monument removal goes on, and on, and on. Columbus statues have been taken down or are scheduled for removal in Camden, New Jersey; Columbia, South Carolina; Chula Vista, California; Detroit; Hartford; New Haven; San Francisco; and numerous other cities. You can’t see them anymore.

Black Lives Matter protestors attacked the monument to Robert E. Lee following the death of George Floyd, but for the moment the statue continues to stand. Its fate may be decided in the courts. Photo courtesy of NBCchicago.com

Some of the lost history may never be replaced. Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, the fourth California mission established by Fr. Junipero Serra, has served Catholics in the western San Gabriel Valley for 250 years. Last summer, the Church removed a statue of Serra to prevent it from being vandalized. [Editor’s Note: A few weeks later, on July 11 a local man set a fire that gutted the sanctuary. Local officials doubt the mission will be rebuilt.]

Along the Pacific Coast today cities are removing monuments for fear of vandalism. One such incident occurred in Portland, Oregon, where the city was forced to relocate a 120-year-old statue of an elk because it had been damaged by protestors. It bears repeating: the city was forced to remove a 120-year-old statue of an elk because it had been damaged by protestors.

Truth and Reconciliation

Self-awareness? Self-flagellation? A teachable moment? How does one describe the preservation of objectionable monuments that have been embellished with opposing viewpoints in the form of equivalent or explanatory memorials? Does the addition of a clarifying historical marker justify the conservation of a racist’s cenotaph? Does the erection of a bronze honoring a heroic Black person legitimize the continued existence of a statue of a slave-holder across the street? Can there even be an honest, two-sided, even-handed conversation about racism, sexism, genocide, and slavery?

The answer, as it turns out, in a roundabout way, with no certainty, is a definite maybe.

To wit: Manzanar. Anyone who grew up in California knows that name. Manzanar War Relocation Center was an internment camp established in March 1942 by the federal War Relocation Authority, where some 11,000 U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated on the off chance that they might sympathize with the Japanese war effort. The detainees, in many cases, lost their homes, their businesses and their life savings before they were ultimately released. The federal government destroyed the camps after the war’s conclusion. But years later, in contrast to the tear-it-down movement, the National Park Service rebuilt parts of the Manzanar facility so visitors could better understand this chapter in the nation’s history. In other words, a controversial relic that had been razed was actually put back in place, rebuilt, specifically so people would remember it.

The cities’ point of view in these matters is not always a knee-jerk reaction to political correctness. Many monuments are removed for fear of vandalism by protestors. One such incident occurred in Portland, Oregon, where the city was forced to remove a 120-year-old statue of an elk because it had been damaged by protestors. It bears repeating: the city was forced to remove a 120-year-old statue of an elk because it had been damaged by protestors.

The Manzanar National Historic Site in California’s Eastern Sierra is a recreation of the camp where many Japanese families were forced to spend much of World War II. It is administered by the National Park Service.

Georgia might not at first strike you as a leader among states confronting their racist past, but if so, you would be surprised. “In Georgia,” says Mark Jaronski of Explore Georgia, “there’s a historical society…that’s led by professional historians. They have the responsibility of the Georgia Historical Markers program.” That program was established in 1998 with the charter to deal with the question of how a state balances the discrepancies between its past and its future. Since then, he says, the organization has established some 250 markers, including new topics about lynchings, women’s rights, minorities, racial violence, and slave sales. “It’s a model way of doing this,” Jaronski says.

While researching this article, I spent an hour on the telephone with Matthew Maxey, the associate director of public relations for Visit Franklin in Franklin, Tennessee. Maxey’s story of how the town came to grips with its Confederate past is instructive.

One of the major monuments in the town, perhaps the preeminent one, is a statue of a generic Rebel soldier, situated in the main square and very prominent in Franklin’s cityscape. The question facing the town: do we save the statue, tear it down, or deal with it in some other way?

Franklin’s efforts to address its past have been formalized as the Fuller Story Project—fuller, as in “more complete.” The Fuller Story designation resulted from a prayer vigil in the Franklin town square following the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. The morning after the prayer vigil, chatting over coffee, the pastors who organized the convocation and the CEO of the Battle of Franklin Trust wondered what they could do to take a more concrete positive step. Someone suggested that they tell the story of the town’s disenfranchised Black citizens. Although they would never be able to tell the full story, they could tell a “fuller” story.

The project attempts to explain and interpret several incidents in Franklin’s past. In a series of five historical markers around the main square and the Confederate memorial, visitors and locals alike can learn about the Riot of 1867, in which animosity among many local white and Black residents resulted in deadly violence; Reconstruction, the federal-led, post-Civil-War effort toward equality in the South that lasted only twelve years; the bloody Civil War Battle of Franklin, in which some 10,000 soldiers on both sides were killed; Franklin Town Square, where the courthouse still stands, in front of which hundreds of local Black men enlisted in the U.S. Army following the Union victory at the Battle of Franklin; and the U.S. Colored Troops, the Union designation for the regiments of Black soldiers who enlisted. The next phase of the Fuller Story Project involves the unveiling of a life-size statue of a Black Union soldier, also facing the town square. The statue is planned to be unveiled on Juneteenth–June 19, 2021.

“It’s not always great history that we had,” says Maxey, “but we’ll tell it all.”

Maintaining historical monuments while addressing 21st-century sensitivities may be the biggest challenge of historians in the years ahead. Fergus Bordewich, a historian responding to the contretemps over the renaming of San Francisco’s public schools, wrote an open letter to the San Francisco school board. In it, he argued in favor of confronting our past, not eliminating it.

Union general Ulysses S. Grant won the Civil War and ended slavery when he defeated Robert E. Lee. As president from 1869 to 1877 he protected freed slaves under Reconstruction. Being on the right side of history did not help him or Francis Scott Key, who wrote “The Star Spangled Banner,” when “peaceful” demonstrators rampaged across San Francisco in 2020. Also vandalized was a bust of Spanish novelist Miguel Cervantes, author of “Don Quixote.” Cervantes himself was once held as a slave, but BLM labeled him a “Bastard” anyway. Photo by hoodline.com

“My point,” Bordewich wrote, “is to suggest that education is better served by facing and exploring the paradoxes of historical figures than by ‘airbrushing’ them from memory the way certain authoritarian countries have done with individuals who have fallen out of favor.”

Another historian contributing to that discussion took a slightly different tack, but one that could easily apply to our national debate on controversial historical monuments. Robert W. Cherny is an emeritus professor of history at San Francisco State University. His comments, while focused on the renaming of schools, could have been directed at America’s historic monuments in general.

“In my research,” Cherny wrote, “it has always been clear to me that that there are few historical figures who do not have some flaw. In my teaching and writing, I gave due attention to the flaws of historical figures as well as to such positive contributions as extending democracy, promoting equality and equity, and otherwise benefitting humanity.

“Schools,” he continued, though he could as easily have been referring to monuments, statues, or other historical memorials, “are not named in recognition or celebration of their namesakes’ flaws, but instead in recognition of their positive accomplishments.” ![]()

Mark Orwoll formerly was International Editor of Travel + Leisure. His articles have appeared in Town & Country, Condé Nast Traveler, The Travel Channel, Frommer’s Travel, and numerous other magazines and websites. His book, John Wayne Speaks, is scheduled to be published by St. Martin’s Press in the fall of 2021.