Jack Daniel statue at the Jack Daniel’s visitor center in Lynchburg, Tennessee. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Jack Daniel and Nearest Green are practically joined at the barrel stave.

By Tom Adkinson

Tennessee has two products that are famous around the world – country music from Nashville and Jack Daniel’s Whiskey from the tiny town of Lynchburg about 80 miles south of Nashville and 25 miles north of the Alabama state line. The story of how country music blossomed in Nashville is well documented, but the origin story of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey has been one that few people even thought about – until recently.

Newcomers to the delights of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey often don’t realize that Jack Daniel was a real person, and even if they do, they don’t pause in a liquor store’s whiskey aisle or on a barstool to consider how the product bearing his name got its start and now is sold legally in at least 170 countries (and imported surreptitiously into at least a couple of others).

I play a game of cataloging where I’ve raised a glass of Jack’s amber liquid. The most unexpected was deep in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador on a rickety overnight excursion boat. Perhaps the most delightful was accepting a generously poured sample in the Manchester, England, airport. So, what if it was 10 a.m.? It was free whiskey.

How It Began

In a sense, the origin of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey is simple. Jack, of course, wasn’t born knowing how to distill whiskey. He had to have a teacher. That guide into whiskey making was Nathan Green.

Green, who went by “Nearest” instead of Nathan and was known to most as “Uncle Nearest,” had much in common with Jack Daniel. Nearest and Jack shared the bond of being born poor in the 1800s, but Jack was born white and poor, while Nearest was born black and enslaved. Their exact birth dates are debated, but Nearest was about 30 years older than Jack. He was born in Maryland in 1820 and ended up in Middle Tennessee, where his reputation grew as a highly regarded distiller.

They met on the farm of Dan Call, a farmer, grocer and preacher, near Lynchburg sometime in the 1850s. Jack, at most a teenager, was a virtual orphan, and he arrived as a farmhand. Nearest had mastered a special technique called the Lincoln County Process that filtered spirits through feet of sugar maple hardwood charcoal, smoothing out the taste of the raw whiskey. Jack became his understudy, lapping up knowledge. This was before the Civil War, so Jack and Nearest worked for the same man but under decidedly different arrangements.

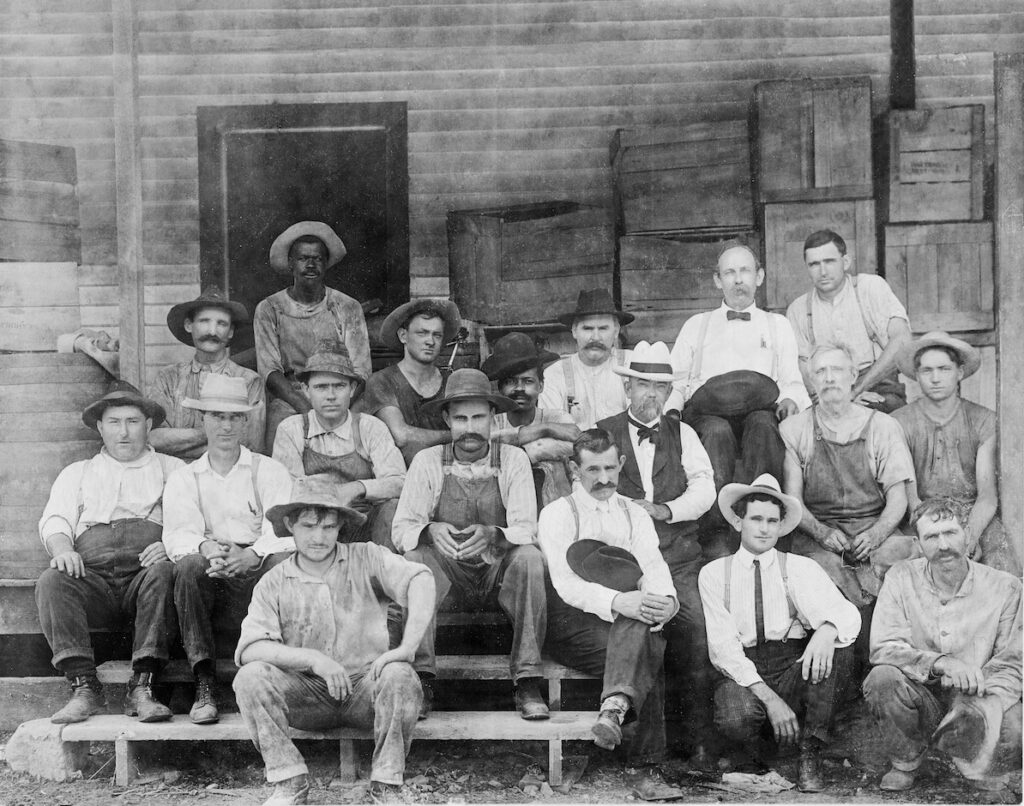

Historic photo of Jack Daniel and crew. George Green, son of Nearest Green, had a place of honor next to distillery owner Jack Daniel in this circa 1904 photo. The photo shows the bond between Daniel and the family of the man who mentored him in the distilling business. Photo courtesy of the Jack Daniel Distillery

What Came Next – A New Relationship

After the war, Jack’s entrepreneurial nature kicked into gear, while Nearest adjusted to an existence he had never known – freedom and farming his own land. However, he and Jack continued to distill whiskey, but with Dan Call eventually out of the picture. The story is that Call’s wife and congregation told him to choose between whiskey and the pulpit. He chose the pulpit and sold his distilling operation to Jack.

Jack hired Nearest, who became the first head distiller for Jack Daniel’s operation. No one could have foreseen the eventual international impact of their whiskey, and although their working relationship was known all around Lynchburg, documenting that was not anything anyone considered. They had whiskey to make, market and distribute. (The company cites 1866 as the year the Jack Daniel Distillery became the first registered distillery in the U.S. It is on the National Register of Historic Places.)

Nearest’s role as head distiller, what now is called master distiller, was significant. A master distiller determines the quality of the whiskey, so he and Jack had a bond that matured over the years like whiskey in a charred oak barrel.

Distilling requires an abundant supply of top-quality water, and sometime after 1881, Jack moved his operation not far away to Cave Spring Hollow in Lynchburg, where the pristine spring water remains the first ingredient in the whiskey that bears his name. Nearest chose not to work at the new location, but two of his sons, George and Eli, did, as did three grandsons. Ever since, descendants of Nearest Green have worked at the Jack Daniel’s Distillery – even today.

There is no known photograph of Nearest, but a famous photo (circa 1904) of Jack and 17 distillery employees cements the Green family in history. Jack, wearing a vest, bowtie and white hat, is conspicuous, but just as noticeable to his right and in the very center is George Green, Nearest’s son. The only other Black face is on the back row, but George is in a place of honor next to the company proprietor.

Jack died in 1911, and the company passed to his nephew, Lem Motlow. The Motlow family sold it in 1956 to the spirits conglomerate Brown-Forman (Jack Daniel’s, Woodford Reserve, Old Forester, Korbel, Finlandia vodka, El Jimador tequila, Chambord liqueur and more).

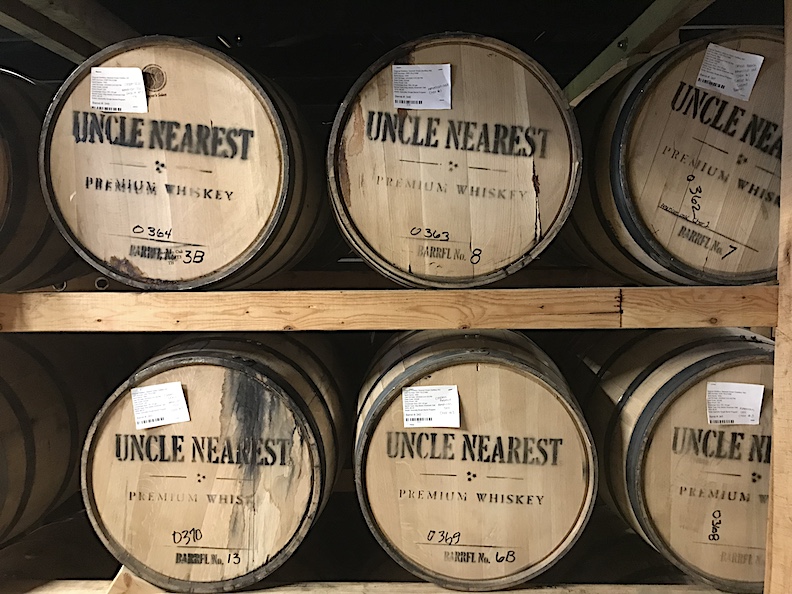

Charred white oak barrels of Uncle Nearest Whiskey spend years in barrel houses before the whiskey is mature and ready to bottle. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Over the decades and generations, the story of Nearest Green faded. Other aspects of the whiskey were the objects of interest, publicity and promotion, but people in Lynchburg – and especially story keepers in the Green family – remembered how Nearest and Jack crushed grain, made charcoal, fired up the still, and secured the reputation for a top-quality product.

The Story Re-Emerges

As Jack Daniel’s Whiskey neared its 150th anniversary in 2016, Brown-Forman pitched The New York Times on a story about Jack Daniel and Nearest Green. Nelson Eddy, the Jack Daniel’s historian, observed, “We didn’t understand how important this story was . . . it’s much bigger than whiskey.”

Fawn Weaver was an unlikely candidate to seize that story and put Nearest Green in a much bigger spotlight. She was a Black Los Angeles author and entrepreneur, and her husband Keith was a Sony Entertainment Pictures executive. They’d never been to Tennessee when Weaver saw the Times article. The provocative headline read, “Jack Daniel’s Embraces a Hidden Ingredient: Help from a Slave.”

We’ll Always Have Lynchburg

Fawn Weaver (in red dress) had no connection to the Nearest Green story until she became the defacto family historian and eventual creator of the Uncle Nearest brand. With her is Uncle Nearest’s great-great-great-granddaughter, the brand’s master blender. Photo by Tom Adkinson

The complete history, as noted above, is decidedly more nuanced. Weaver was intrigued. As she wrote in “Love & Whiskey,” her 2024 book about Nearest Green and the whiskey business he eventually created, “I knew I’d stumbled upon a damn good story.” Her 40th birthday was approaching, and her husband lobbied for Rome or Paris as a celebration destination. She insisted on Lynchburg.

What she found was that Nearest Green was not part of the tour guides’ narrative at the Jack Daniel Distillery or acknowledged in the visitor center, despite the fact Nearest had taught Jack how to make whiskey and had been beside him at the very start of his business. She began a protracted historical and genealogical research program that started with conversations with aging members of the Green family and continued with archival trips to Nashville, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., St. Louis and elsewhere to find census records, court papers and other documentation.

She constructed a Green family tree that went far beyond the memories of a handful of people and entries in family Bibles. She also worked closely with Daniel and Motlow sources and gradually verified and documented the connection between Jack and Nearest. She became so entranced by the story that she and her husband jumped on an opportunity to buy the Dan Call Farm, the very place Nearest introduced Jack to whiskey making.

After Weaver had all the history in place, she coordinated a gathering of Nearest’s descendants. She described the meeting in her book and asked what the family wanted from the information she presented. She said one man spoke up to say, “We think Nearest deserves to have his own bottle.”

What that meant was that they wanted a whiskey with Nearest’s name on it, and Weaver reacted on the spot with, “We’ll do it. We’ll raise the money.” The reality was that she herself would have to raise the money and become the CEO of a company distilling whiskey to honor Nearest’s legacy. The dispersed Green descendants didn’t have the business acumen or connections to pursue that goal. She said her husband was “a little shell-shocked,” but they dove in.

“The reason we all know about Johnnie Walker, Jim Beam and Jack Daniel is because we constantly see their bottles and say their names. They’re the Mount Rushmore of whiskey. Putting Nearest’s name on a bottle was the only way to carve him into that mountain,” she wrote in “Love & Whiskey,” adding that the goal was to be national, not niche, and to appeal to all drinkers, not just a subset.

Creating a business in an industry of established giants was challenging, even arduous – finding the initial source whiskey, acquiring barrels, convincing distributors to carry the product, persuading restaurants and bars to put it on their menus, working through America’s maze of liquor regulations. It was like building an airplane while already flying it.

Victoria Eady Butler always knew her great-great-great grandfather was instrumental in the creation of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey. Now as the master blender of Uncle Nearest Whiskey, she says “whiskey truly is in my blood.” Photo by Tom Adkinson.

“If you look at the moves I was making, I should have failed. But they were the right moves,” she said in July during a book tour.

All the whiskey lines from the Nearest Green Distillery have the “Uncle Nearest” name, and they are tied to Nearest in a fashion straight out of a movie because the master blender is Victoria Eady Butler, the great-great-great granddaughter of Nearest himself.

“We (my family) always knew the story of Nearest. My grandmother taught us all,” Butler said, but her own career had been elsewhere, leading a team of criminal and forensic analysts for a Department of Justice-funded information network.

“Whiskey truly is in my blood,” she said of her previously unidentified skill of blending whiskey that earned her industry-wide “Master Blender of the Year” accolades for four years and helped Uncle Nearest products win more awards in American whiskey competitions than any other label every year between 2019 and 2023.

By 2020, Uncle Nearest was the fastest-growing Black-owned spirit brand ever and by 2024 crossed the $100 million mark in sales. The company’s valuation is around $1.5 billion, according to Weaver.

Where To Get In On the Action

Distillery tours are part of the business plan for many distilleries, but the Nearest Green Distillery goes a step farther.

One of the many bartenders mixes a drink behind the world’s longest bar (518 feet) that is the centerpiece of an active entertainment venue called the Humble Baron. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, it is the longest bar in the world. Also perhaps the most crowded at certain times of the week. Photo by Tom Adkinson

After acquiring the Dan Call Farm and while creating her company, Weaver encountered another real estate opportunity – land that had been a horse farm, complete with some substantial buildings convertible into a showplace distillery, tour location and an entertainment venue.

A $50 million buildout has begun on 458 acres of Tennessee countryside. One of its bragging points is the Humble Baron, a 500-person venue with what Guinness World Records cites as the longest bar in the world. The 518-foot-long serpentine oak bar has 202 seats, and the whole space is used on Thursdays for country music and line dancing, Fridays for music ranging from country to rhythm and blues, Saturdays for rhythm and blues and soul music, and Sundays for a gospel brunch.

Tastings occur in a more intimate location where visitors are offered Uncle Nearest 1884 (a small batch 93 proof product), Uncle Nearest 1856 (named for the year the Lincoln County Process was first documented), Uncle Nearest Rye and Uncle Nearest Master Blend (a 121.8 proof whiskey sold only at the distillery).

For decades, people have made pilgrimages to tour the Jack Daniel Distillery in Lynchburg, which is about 75 miles southeast of Nashville in Moore County. Today, travelers on that route pass right by the Nearest Green Distillery outside Shelbyville in Bedford County. The two attractions are only 25 miles apart, giving the region a one-two tourism punch.

Visitors to the Nearest Green Distillery wait for instructions and descriptions of the four Uncle Nearest samples they will taste on a distillery tour. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Nearest And Jack Today

“We’re not just neighbors, we’re collegial neighbors,” is how historian Eddy described the relationship between the two distilleries.

In 2020, the companies aligned to fund the $5 million three-part Nearest & Jack Advancement Initiative. One component is a leadership acceleration program that creates advanced apprenticeships for people of color already in the spirits industry. The second is a business incubation program that educates and encourages minority entrepreneurs, and the third is the Nearest Green School of Distilling at nearby Motlow State College.

Eddy said the inter-company connections – and the illumination of Nearest Green’s role in American whiskey making – are “good for the Jack Daniel Distillery, good for the Nearest Green Distillery and good for American culture.”

Weaver echoed that sentiment: “When Jack Daniel started his company he didn’t see race as a barrier. Nearest and Jack were friends, and I think they are walking around in heaven and having a hoot.”

Visitors to the Jack Daniel Distillery get a full explanation of the bond between Nearest Green and Jack Daniel and how they worked together. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Finding A Taste For Whiskey

To paraphrase U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s threshold test for obscenity (“I know it when I see it”), any individual’s threshold test for good whiskey should be “I know it when I taste it.” There is that much variation.

Master distillers and master blenders have the special talent to create products that have a consistent taste. Whether they are born with special skills or have trained their palates to detect subtleties others can’t is immaterial. What consumers want is the assurance that one bottle of whiskey they enjoy will taste the same as another bottle of the same label purchased at a different time.

They also want to know that a bottle identified as special and different – and probably priced accordingly – truly is special and different.

That’s what makes distillery tour tastings both entertaining and informative. A good guide can walk you through differences you might not detect without some coaching – and it’s possible your palate may never taste what the guide describes.

Are charcoal-filtered Tennessee whiskeys such as Uncle Nearest and Jack Daniel’s really smoother than Kentucky’s most famous bourbons that aren’t? Is one distiller’s rye whiskey really spicier than another’s? Is a 121-proof premium whiskey so different from your norm that you can truly appreciate it? In all cases, you won’t know until you try.![]()

EWNS Contributor Tom Adkinson lives in Nashville. Other stories by Tom described Charleston’s Afro-American Museum and profiled the world’s best places to observe the Celestial Night Sky.