Hostess welcomes visitors to the Dar Annabi, a private home and modestly priced museum that’s open for public viewing during mid-day hours. Constructed in the 18th century, it was remodeled to provide modern conveniences for the resident owners.

By Charles Cecil

The Tunisian suburb of Sidi Bou Said, a welcoming hilltop village about twelve miles north of Tunisia’s capital of Tunis, overlooks the ruins of ancient Carthage. It offers intimate cafés, locally-made handicrafts and stunning views of the Mediterranean. Locals call the hillside Kursi al-Sulh, ‘the seat of reconciliation,” since in former days it was a quiet place where Muslim holy men retreated for repose and meditation. The town’s name is derived from a religious figure, Abu Said al-Baji, who died in 1231 AD and is buried beside the town’s minaret in a mausoleum built during the period of Turkish rule.

In ancient times the Phoenicians, who dominated maritime trade for more than 1,000 years until supplanted by the Romans, built a lighthouse on this hill where a fire marked the entrance to the Bay of Tunis. Legend says that the house of Hamilcar, father of Hannibal, was on this site, but development over the past two hundred years makes it unlikely archaeological evidence will ever be found.

From this location in 146 BC you could have watched the Roman destruction of Carthage, a few kilometers away at the base of the hill. In 19 BC you might have observed the arrival of 3,000 Roman colonists assigned to rebuild the storied entrepot by the emperor Augustus. In 1270, you would have seen the entire army of France camped on the shore while their king, Louis IX, lay in his tent dying of fever.

During the two years I lived and worked in Sidi Bou Said, it was a village of white stuccoed buildings adorned by Mediterranean blue doors and ornate grillwork. Today it remains a place popular not only with foreign tourists but also with Tunisians who come on weekends to enjoy the many restaurants, small coffee houses and stunning views of the Mediterranean.

Sidi Bou Said sits on a hilltop 20 minutes outside Tunis. Ruins of the 4th century Byzantine Basilica of Damous Karita are in the foreground.

Many residents work in Tunis, twenty minutes away, but prefer to live among the gentle breezes enjoyed on the hilltop. This favorable location and pleasant atmosphere led to Sidi Bou Said’s growth in the middle of the 19th century as members of the upper class of Tunis built country residences and weekend retreats on the hilltop. Strict architectural regulations preserve the appearance and ambiance of the village as it was in the early twentieth century. Nothing new can be constructed which does not conform to strict traditional requirements. Buildings, doors, and grill work must be repainted periodically on a schedule maintained by local authorities.

Much credit for preserving this architectural heritage is given to Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger, a French musicologist and painter, who lived here in the 1920s. His home, Ennejma Ezzahra, “the Star of Venus,” is now a museum that houses the Centre for Arabic and Mediterranean Music, an institution that maintains a collection of musical instruments in addition to organizing concerts of classical and Arabic music to promote Tunisia’s musical traditions.

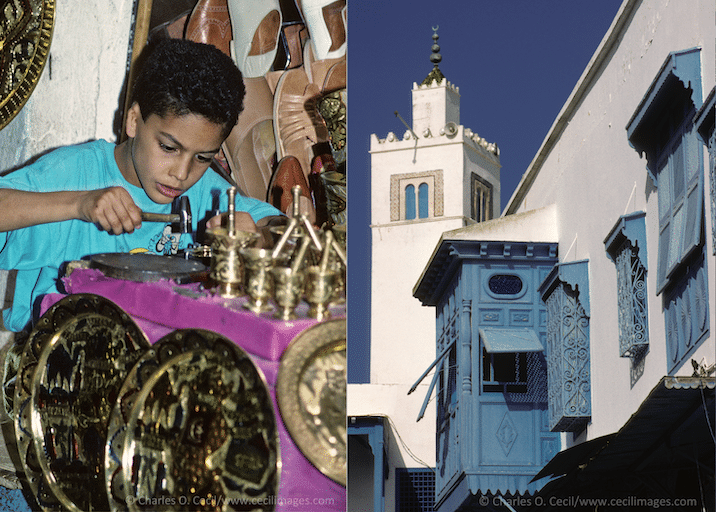

As you make your way up the street toward the Café des Nattes you’ll pass handicraft makers and vendors displaying a wide variety of metal trays and dishes, ceramics, and textiles, as well as an art gallery with rotating exhibits. Nearby vendors sell fried donuts called bambaloni and a seemingly infinite variety of “Turkish delight,” nougat, and other candies.

Young girl buying cookies from a man wearing a Chechia, a traditional Tunisian hat.

If you need to rest while making your way up the hill look for my favorite bench on the left, opposite the vendors’ shops on the right. Old ceramic tiles, probably dating from the early twentieth century, hint at both Tunisia’s rich ceramic artistry traditions, and testify to generations of visitors who have stopped to rest while climbing the hill.

Citizens of Sidi Bou Said gather after work and on weekends in front of the popular Cafe des Nattes.

Farther on is another café built around the mausoleum of another holy man. It’s called the Cafe Sidi Sha’ban, but also goes by the name Café des Delices. It’s very popular with well-established locals, who enjoy the view of the Bay of Tunis and Carthage down below. Unfortunately this coffee shop has gained a reputation for rudeness, poor service, and outrageous prices charged to tourists. While it offers a wonderful view it must be approached with caution.

Just past the Sidi Sha’ban the road comes to an end in front of a traditional upper-class home. It is typical of 19th century villas with decorated doors that open onto an intriguing courtyard. In elegant traditional villas like Dar Annabi the door knockers are high on the door. They date from a period when visitors arrived on horseback and preferred to knock before dismounting.

This 19th century courtyard residence was built in a period when visitors arrived on horseback. The door knockers were set high so they did not have to dismount to make their presence known.

The best way to enjoy Sidi Bou Said is to arrive early-morning so you have plenty of time to walk the streets, admire the handicrafts and souvenirs on sale, visit the Dar Annabi and Ennejma Ezzahra museums and make your way to the Café des Nattes under the minaret near the top of the hill. Once refreshed, check the best tourist advisories for café reviews to choose a place for lunch. Somewhere along the way you’ll want to buy a jasmine sprig from a vendor. Perched snugly behind your ear it will provide a pleasant aroma for the rest of the day.

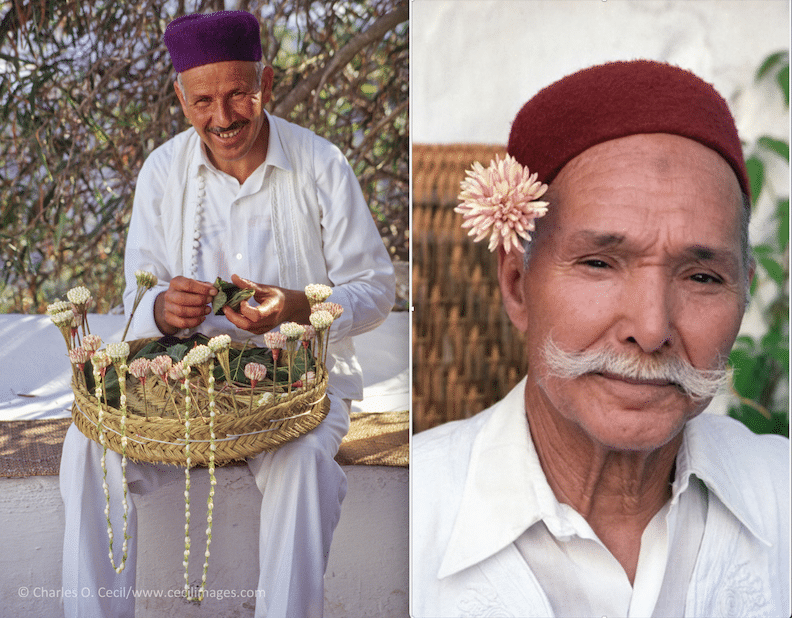

Jasmine vendor, left, finds a loyal customer in café owner Haj Omar

After lunch make your way down the hill to the lower part of the town where you can hire a taxi for two nearby side trips that should not be missed while you are in the area. The first is the 19th century St. Louis Cathedral, now sometimes called the Acropolium, a Byzantine-Moorish relic of the French colonial era when a sizeable Christian community of businessmen and colonial administrators lived in the suburbs of Tunis. The cathedral sits atop the Byrsa Hill, site of a temple in Carthaginian times. Nearby is the Carthage National Museum.

From this hill you can see the remains of the Punic Ports of Carthage that now resemble small lakes bordered by luxurious homes. The ports date from the 4th century B.C. The foreground was the naval, or military, port. The commercial port is adjacent, farther back, with the Bay of Tunis in the background. Imagine the activity one could have seen when Carthage was at its height as a Mediterranean trading power.

Carthage, Tunisia. Punic Ports, now resembling small lakes bordered by luxurious homes, date from the 4th. Century B.C. The foreground was the naval, or military, port. The commercial port is adjacent, farther back. Bay of Tunis in the background.

A few minutes down the hill are the remains of the Roman Arena of Carthage. This is one of the most historic sites of the early Christian church in North Africa for it is here Saints Perpetua and Felicity were martyred. Over the centuries local residents have carted stones away to use in private construction; nothing remains of the high stone bleachers that once seated 36,000 spectators. But in this circle Christian martyrs met their death on March 7, 203 A.D. for refusing to give up their faith. An underground room was discovered in 1881, in which prisoners were held while awaiting their turn in the arena.

The events of that day have been preserved in several historical sources. Drawing on what we would today call eye-witness accounts, Alban Butler, a 17th century English Catholic historian, described the ordeal. Saint Perpetua, a young girl of 22, after being gored and tossed by a mad bull then faced a young and inexperienced gladiator “…who, with trembling hand, gave her many slight wounds, which made her languish a long time.”

Other saints including Saturus, Saturninus, and Revocatus, followed Perpetua and Felicity into the arena to their deaths. In the words of St. Augustine of Canterbury, who introduced Christianity to southern England in the late 6th century, “Thus did two women, amidst fierce beasts and the swords of gladiators, vanquish the devil and all his fury.”

Carthage, Tunisia. Remains of the Roman Arena, Site of the Martyrdom of Saints Perpetua and Felicity in 203 A.D.

There are other evocative Punic and Roman ruins nearby in Carthage. Depending on your pace and stamina you might find it best to dedicate a leisurely day to Sidi Bou Said, and use a second day for the Roman arena, the cathedral, the Carthage Museum, and the Punic ports.

The cisterns of La Malga, which held the water supply for Roman Carthage, is another incredible example of Roman engineering. This entire area north of Tunis is rich in history. Be generous in the time you allow for it and you’ll enjoy your visit much more.

Young Tunisian artisans produce intricate metal plates on a busy shopping street not far from a traditional residence built at the base of a minaret. The blue “harem window” is constructed so cloistered women could have a better view of the street outside the house where they lived.

Except in mosques, where non-Muslims are generally not allowed entry, Tunisians welcome tourists who make a significant contribution to the economy. COVID restrictions have greatly diminished foreign travel the past year, but as international travel returns to normal Sidi Bou Said quickly will resume its place as one of Tunisia’s most popular tourist destinations. ![]()

Charles Cecil served as Director of the U.S. State Department’s Arabic Language school in Sidi Bou Said for two years. Please see Cecil’s Featured Photography photo essays on Goree Island, Senegal and Bhutan elsewhere on this site, or his article about the many uses of gum Arabic, a topic he pursued while U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Niger. For more of Cecil’s photos of cultures in the developing world, see http://www.cecilimages.com/