Across the broad Rio de la Plata from Argentina is the 17th century village of Colonia del Sacramento, a relaxed city of pastel buildings, cobblestone streets and seven excellent museums.

“You’re going to Uruguay?!” The excitement sang in my daughter’s e-mail. My spontaneous decision to visit the tiny country sandwiched between the larger nations of Argentina and Brazil had caught her by surprise. Frankly, I am just as surprised. Uruguay? It never entered my mind,

But that was before I met an exuberant Uruguayan woman on my flight from Toronto to Buenos Aires. Seatmates, we chatted about travels, families and life. When she invited me to her beach house in her native Uruguay, naturally I accepted. After all, I might never be here again. Wrong. Several visits later, Uruguay still exerts its magic.

The fast ferry (“Buquebus”) from Buenos Aires takes an hour and fifteen minutes to reach Colonia del Sacramento, flying directly across the fresh water “sea,” the Rio de la Plata, the world’s widest river. Alighting at Colonia, a charming UNESCO World Heritage town founded in 1680 by the Portuguese, I closed the door on hectic Buenos Aires.

“It’s like a movie set,” I thought, buildings painted ochre, yellow, and pale blue, avenues of spotted plane trees casting dappled shadows. Walking under the drawbridge gate from the ferry, I came to the cobblestone “Street of Sighs,” a lover’s lane dating back to the 17th century. Streets and squares are dotted with permanently parked cars from the 1940s and 50s. These cachilas are home to flower displays or decorative ads for cafes and restaurants.

Often adorned with displays of flowers, antique cars from the 1930s and 1940s called “cachilas” serve as urban art when permanently parked on the cobblestone streets of Colonia del Sacramento

On my very first visit, an hour’s drive over the flat pampas took me to my new friend’s beach house, where a gently sloping eucalyptus forest led us into the cooling shallows of The Rio de la Plata, a river so wide that all of Belgium could fit inside it.

On my next trip to Colonia, I brought along my husband. Luckily, we happened on a film set this time, a real one. Actors in nineteenth century garb hung about Colonia’s main square, posing for our cameras between takes. Their faces could have belonged to immigrants who came here centuries back: Spanish, Italian, African, and a smattering of Germans, Swiss, Basque, English.

These actors may be dressed in 19th century attire. But they accurately represent the diverse ethnicities comprising modern Uruguay.

Today a sibling rivalry exists between Argentina and Uruguay. “They hate us because we have better beaches,” my airplane friend tells me, her opinion confirmed by an opera-loving Buenos Aires native. “Yes, it’s true,” he laughs. Uruguay’s beaches have always been bigger and better than Argentina’s, but in the 18th century there was considerable antagonism between the neighbors to necessitate the building of a drawbridge.

The bilingual folks at the Info Turismo tell me that the 1745 drawbridge was built to protect the walled town during the tumultuous 18th century. Gentle Colonia del Sacramento was in fact founded as a fortified base from which to move contraband through the patchwork isles of the Rio de la Plata, a practice that lasted more than a century as Portugal and Spain vied over what the tourist brochures call, in a nicely mythological touch, “the apple of discord,” a conflict that ended with Uruguay’s independence in 1828.

Shortly after independence, diplomatic relations with the USA were established, and today the country—one of the smallest in South America—numbers about 3.5 million, boasting one of the continent’s most successful economies, with a robust middle class, high literacy rates, and tolerant policies that include same sex marriage and legalization of cannabis (for its citizens).

Colonia’s zigzagging streets open, puzzle-like, onto small plazas that date as far back as Portuguese times. “Decompress,” they seem to say. “Relax.” Fountains of pink and purple bougainvillea pour over stone cottages; gracious old restaurants like the Meson de la Plaza celebrate the three-hour lunch. Specialties lean to the carnivorous, the favorite local dish a selection of grilled or barbecued meats, called asado. Local fish is also excellent; dulche de leche and flan are favorite desserts. Menus are similar to those you’ll find in Argentina.

Blessed with tree-lined boulevards, immaculate gardens, broad esplanades and dozens of boutiques and galleries, Montevideo is a cosmopolitan jewel with a sophisticated population.

Recently Uruguayan wines have been making a splash, but the national libation remains yerba maté, a pungent herbal tea sipped from vegetable gourds through metal straws. Maté sippers are here, there, everywhere. People walk the streets with their gourds and straws; this naturally caffeinated drink is packed with vitamins and is apparently good for weight loss too. The taste takes some getting used to, but above all it’s convivial; people share.

Open-air cafes, artisans’ shops selling designer woolens, and centuries of history attract throngs of day-trippers. There’s the Portuguese museum and the Spanish Museum. Colonia offers seven museums in all, one devoted entirely to tiles. Among other oddities, the town boasts a bullfighting ring–last used in 1912–that once drew thousands to watch Spanish toreadors.

Today Colonia seems to be a city happily lost in time. It’s easy to imagine Marcello Mastroianni here, the star of I Don’t Want to Talk About It, a 1994 film about an aging roué in love with the wrong sister. Wandering the old streets in his white linen suit, slightly mad, wholly charming, Marcello would not seem out of place.

Tearing ourselves away from Colonia, we head to the capital, Montevideo, about 112 miles east of Colonia on the coast. Like everything else in Uruguay, Montevideo (founded in 1724) seems on the small side, with a population of less than one and a half million. At first blush it seems like a miniature Buenos Aires, with its grand squares, shaded gardens, flowering trees, and a myriad of theaters, galleries and bookshops.

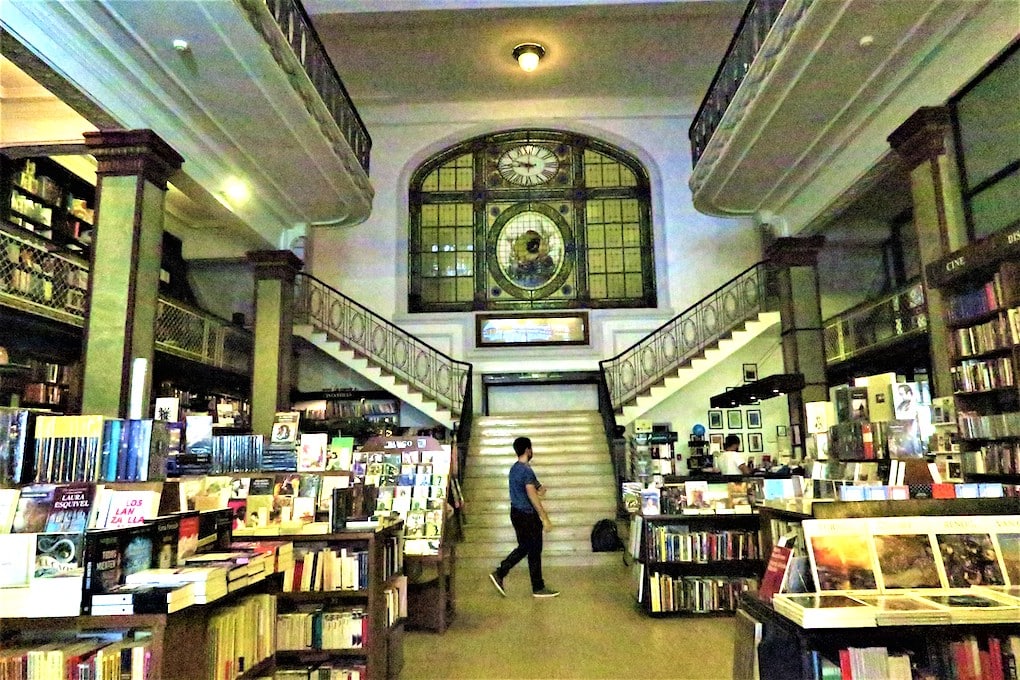

Montevideo’s Art Deco, Colonial and Belle Epoque architecture extends into the interiors of buildings. This bookshop exudes a cultured ambience in part because of the amazing attention to period detail.

On the evening of our arrival in the Pocitos neighborhood, we join the joggers and strollers on La Rambla, the paved path above the sandy beaches of Rio de la Plata. The sun was slipping below the horizon, the near-empty beach stretched for miles, and life seem perfect.

Montevideo, we discovered, offers its very own surprises. “We have more Art Deco buildings than Miami,” I’m told by Uruguayan native Jörg Thomsen, a businessman whose personal addition to Montevideo’s cultural scene is the seven-year-old Museo Andes1972, a moving homage to the rugby team members who survived seventy-two days in the high Andes after their plane crashed–a worldwide sensation that inspired several books and movies.

Art Deco, Colonial and Belle Epoque architecture graces Montevideo’s cityscape, along with the outright weird. On our first night we spotted the eccentric Castillo Pittamiglio, home to an architect obsessed with alchemical symbols. Is that a Winged Victory of Samothrace flying from the house toward the river? Yes, it is.

Located on Montevideo’s Rambla, Pittamiglio Castle was designed by an alchemist who covered much of the interior with obscure symbols. He never managed to turn base metal into gold but he did succeed in adorning the castle’s exterior with a replica of the Winged Victory of Samothrace.

What economy, we wondered, financed these fancies of yesteryear? Simply put, beef and other agricultural exports. Farmers have traditionally done well in Uruguay; this small country supposedly has more cows than people. Montevideo’s skyline was underwritten by prosperous cattle exports. Oxo (beef cubes) and Fray Bentos (tinned corned beef and meat pies) dominated markets in in England and Australia for years. A well-educated work force has added IT and consulting services, while tourists and retirees are increasingly drawn to this pleasant country. Jörg assures us that North Americans can live “better here than at home.”

Hundreds of years ago, Montevideo’s port housed a large slave market; a trade banned in1816. Today about 15% of Uruguayans claim Afro-Uruguayan roots. A point of cultural pride are the wooden African drums called candombe, shaped like large barrels. A highlight at Carnival, candombe are played throughout the year; rocker Mick Jagger visited a candombe club during his visit.

In our two day stop in Montevideo, we strolled the Old City center, immersed ourselves in the not-to-be-missed MuseoAndes1972, and became acquainted with artist José Gurvitch, who immigrated from Lithuania at age five and has an entire museum dedicated to his bright, colorful, geometric paintings. After stocking up on picnic supplies at the restored 1910 Mercado Agricole, we drove further up the coast. Our goal is the beach resort of Punta del Este, eighty miles to the east.

A confession: I get carsick. So, we stopped in Piriápolis, where we discovered the 1930 Hotel Argentino, a place that oozes period charm and still attracts a clientele that may remember the 30s. This is old South America at its finest, with a grand staircase, Tiffany-style window, casino, elegant dining room and gorgeous views over the water. Over English-style tea, we felt part of an older, elegant world.

Punta del Este used to be a fishing village–perched on a narrow peninsula between the Rio de la Plata and the Atlantic Ocean—both shores within walking distance of each other–began its trajectory into glitz with a 1953 film festival. Today the “St. Tropez of Uruguay” attracts a generous share of super models and yachting types in the holiday season, although in February, when we arrived, its upscale neighborhoods seemed ghost-like, their mansions emptied of their partying owners. “This is not Uruguay,” people tell us. It isn’t Colonia, for sure. Luxury condos and casinos line the Rio de la Plata beach; the rougher Atlantic Ocean attracts world-class surfers.

Uruguay’s Atlantic coast beaches have some of the World’s best surfing.

Interestingly, Punta sparkles with an astonishing amount of art. The Ralli Museum houses a permanent collection of South American paintings; a courtyard highlights Salvador Dali’s work and special exhibits feature luminaries like Marc Chagall. One of the world’s five Ralli Museums, the design here mimics a large and lavish Spanish hacienda.

For a few days we stayed at the Barradas Parque Hotel, a few blocks from the glittering river. There we made friends with Facundo Barandas, a genial dentistry student from Montevideo who works summers at the front desk. Facu spoke to us in fluent English about the hotel style: “British.” Uncertain precisely what that means, we opt for relaxed, artistic. Turns out that contemporary English designer Christian Guy designed the furniture. Facu says that this is “an experience rather than a hotel.”

Named for Uruguayan artist Rafael Barradas—whose work hangs in the lobby—the hotel is brightened with prints of English folks enjoying days at the beach in the late 1940s. Splashes of antiques–found by scouring auctions all over Uruguay—complement the décor. In summer, well-known Uruguayan writers host discussions on various topics and artists launch vernissages. Like the Ralli Museum, these hotel “experiences” are free, and popular.

Art in Punta is matched only by its beaches–river or ocean, your choice. Almost twenty miles of shoreline, with piers reminiscent of Old Europe, is complemented by casinos and “wellness” spas like the one at our hotel, specializing not only in exotic Amazonian oils but also in designer CBD and other cannabis-based treatments.

Drawn to the lobby bookcase, I check out the English paperbacks. A tattered Agatha Christie mystery entitled “Destination Unknown,” seems to speak to this corner of Uruguay. Seduced by Punta’s mood of elegant relaxation, transfixed by its sunsets, we soon conclude that, like Bogart in Casablanca, we have been misinformed. We are in Uruguay. The tell-tale clue? Yerba maté, of course. Everywhere we look, vacationing families can be seen indulging in the ritual beverage, pouring portions of tea from large thermoses into small gourds, then sipping, chatting, sipping, laughing.

Hollowed vegetable gourds made to hold bitter maté tea are sold throughout Uruguay along with metal straws for sipping.

Maté is also on offer at our hotel’s lavish buffet breakfasts, so we take the plunge—or the sip. Must be an acquired taste. Gingerly I ask an Argentinian musician friend about the appeal of his morning ritual. Gustavo Bulgach’s answer booms over email: “Bitterness!!! Gets you up in a few sips and no hang ups. Also, a perfect excuse to spend time with people.”

One warm evening we walked over to Club de Pesca, an old-fashioned eatery overlooking the glass-blue Rio de la Plata. At eight o’clock, there were few customers – Uruguayans dine late – and we enjoyed our “quiet night and quiet stars.” An elderly waiter serves generous platters of the best sole ever, homemade papas fritas, beautifully fresh-squeezed orange juice, and, for dessert, creamy, traditional flan.

Punta offers many jazzier nightlife choices—clubs, casinos, discos, popular DJs, flashier dining. In December-January, the super-rich, including super models such as Naomi Campbell, return on their yachts or occupy those mysterious empty houses. March witnesses Formula E-racers tearing around the flat, curved streets of this town of less than 10,000. In fact, President Lyndon Johnson may have first put Punta on the world map when he attended a meeting here that resulted in the forming of the World Trade Organization.

One day we taxi over to Casapueblo, a vast, blindingly white gallery in nearby Punta Ballena, formerly home to the multi-talented Uruguayan artist Carlos Paez Vilaro, whose son numbered among the intrepid survivors of the 1972 Andes crash. The story of their reunion–Paez never gave up searching for his child—makes a touching climax to a visit to this cliffside gallery/museum.

We took the roller-coaster like bridge to La Barra, an old fishing town, and were seriously tempted by a boat tour five miles away to Isla de Lobos and its sea lions. But sleepy days in Punta are made for relaxing. “There’s so much oxygen in the air!” exclaimed Veronica Diaz, a new friend from Montevideo that we met by the hotel pool. So, we lingered over breakfast in the hotel garden, listened to the birds, took in an Amazonian massage, complete with exotic oils, and in late afternoon headed to town for espressos and ice cream.

“Hand” sculpture by Chilean Mario Irararrazbal is an abstract warning to beware the rough Atlantic tides, but these Punta del Este teenagers don’t appear intimidated.

On the Atlantic side, we saw Uruguayan surfers, many of whom rank among the world’s best and kids cheerfully climbing the famous “hand” sculpture by Chilean Mario Irararrazbal. The hand signals the danger of the rough Atlantic waters, but climbing kids are oblivious. Still, there are fewer swimmers on the “Playa Brava” (Strong Beach) than on the “Playa Mansa” (Calm Beach.)

Giant fingers emerging from the sand, sport and culture everywhere you look, an abundance of oxygen and yerba maté—these are among the pleasures in this quirky, elegant beach destination, a century or three from sleepy Colonia del Sacramento.![]()

Nancy Wigston is an award-winning travel writer whose work has appeared in England, South East Asia and her native Canada.