Canalside, located at the 1825 terminus of the Erie Canal, is at the heart of Buffalo’s revitalization district which now includes hotels, food kiosks, activities and more. Winter ice skating gives way to paddle boating in summer, but a party atmosphere prevails in all seasons of the year. Photo by Edward Snell

By Liz Campbell

More than Chicken Wings

Once one of the country’s most prosperous cities at the end of the 19th century, Buffalo by the mid-20th century mainly was known for obsolescence and frigid winters. But through it all, Buffalo held on to what counted – music, art, vintage architecture and a citizenry that never lost its no-nonsense, down-to-earth approach to life. These values, along with the striking progress that has taken place over the last few decades, are why you should visit Buffalo now.

For more than a century, Buffalo was one of America’s busiest cities. The 524-mile Erie Canal opened in 1825, and Buffalo, its western terminus, immediately boomed. Waves of European immigrants from Italy, Germany, Poland and Ireland built new plants, transportation links and manned the steel and grain mills.

In 1843, the world’s first steam-powered grain elevator was constructed by local merchant, Joseph Dart. Nearby Niagara Falls provided the power that made Buffalo America’s first electrified city. Before long, the country’s top architects – men like Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan – were building magnificent buildings for the industrial giants living there.

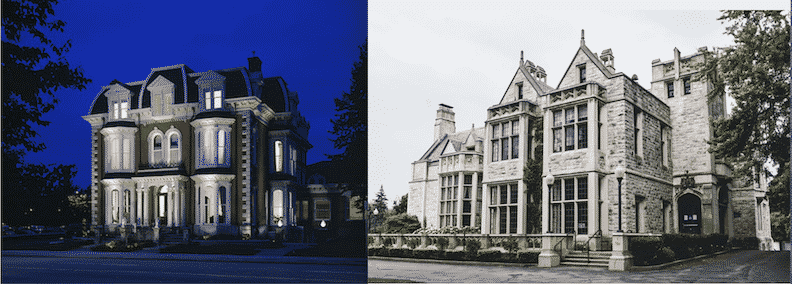

Buffalo’s Delaware Avenue is lined with mansions that are symbolic of a Golden Age that lasted for more than 60 years. The Mansion on Delaware (Left) was built in 1869 for Charles Sternberg, who owned the grain elevators in Buffalo. The Clement Mansion (Right) was a popular gathering spot for Buffalo elitists after it opened in 1914. Clad in gray sandstone, the Tudor Revival has interior floors of diamond-shaped marble and a 1.5-story music room. Local realtors insist you don’t have to be a millionaire to buy one of Buffalo’s mansions today. But a million dollars, they smile, will come in handy if you want to heat your palace all winter. Clement photo by Mike Shriver of BuffaloPhotoBlog.com

The century of hypergrowth ended abruptly in the 1950s when momentum shifted and Buffalo found itself with abandoned silos, warehouses, office buildings, and homes. Ironically, that proved beneficial.

While other cities demolished their 19th century architectural masterpieces to make way for glass and concrete, Buffalo had little incentive to follow suit. It retained gems such as the magnificent Art Deco City Hall with its elaborate entrance frieze representing the growth of industry, art and science. Today, City Hall and the Beaux Arts white wedding cake that is the Electric Building still dominate the urban skyline.

The Beaux Arts style Electric Building stands tall and distinguishes Buffalo’s downtown skyline.

Dozens of handsome old buildings still stand proudly. Buffalo has the distinction of being the only city in America to boast buildings by all three American architectural giants: Louis Sullivan (known as the father of the skyscraper), H.H. Richardson, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

By 1901, Buffalo had 60 millionaires, more per capita than any city in the US. Thoroughfares like Delaware Avenue and Eggertsville Road were lined with massive mansions built by wealthy innovators who revolutionized business and industry. A home for Buffalo industrialist Darwin Martin was Frank Lloyd Wright’s first commission outside Chicago.

In 1904, Martin allowed the charismatic architect to incorporate all his best ideas into one residence that embodied serenity and peace. Now open to the public, with many of its nearly 400 art glass windows restored and much of the original Wright-designed furniture in place, the angular, yellow-brick Darwin Martin house is a place of pilgrimage for Wright devotees.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s first architectural commission outside Chicago was the Darwin Martin House in Buffalo.

Buffalo’s Golden Age

Thanks to its business titans, 19th-century Buffalo was at the epicenter of social, artistic and cultural ferment. The Albright-Knox Gallery, founded in 1862, is one of America’s oldest art institutions. Its extensive collection traces the history of art with examples from every major movement and includes a significant contribution by black artists.

The beautiful Greek Revival structure with its 102 Ionic columns mirrors the Erechtheion atop the Acropolis in Greece. It sits in Delaware Park, another Buffalo triumph. This was the first city in America to create a coordinated system of public parks and parkways at its heart.

The eastern portion of the park’s 350 acres is a rolling meadow dotted with trees and surrounded by woods. In summer, it’s the city’s favorite picnic area. On the west side, scenic Hoyt Lake offers boating in summer and skating in winter. The park’s designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, also designed Central Park in New York and Mont Royal in Montreal.

Near the Western end of the park you’ll find the brick and stone buildings of the Hotel Henry Resort and Conference Centre, once the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane. Built in 1870, the complex was designed by H.H. Richardson for Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a progressive psychiatrist who believed in the value of fresh air, light-filled rooms and wide hallways where residents could gather and mingle. Today, Hotel Henry’s airy, windowed halls, and rooms with 18-ft-high ceilings, create an appealing sense of light and space.

The Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane has been reborn as the Hotel Henry Resort and Conference Center. It’s named for architect Henry H. Richardson, who designed the building. Though its exterior appears austere, the hotel is actually light and airy on the inside.

In the East Aurora section of metropolitan another visionary, Elbert Hubbard, founded Roycroft, an Arts and Crafts community dedicated to the restoration of natural, simple design. Hubbard recruited America’s finest printers, book designers, painters, sculptors, furniture makers, metalsmiths, photographers and writers. By 1902, the Roycroft Campus was a cauldron of creative activity.

The following year, the Roycroft Inn was built to house the influx of visitors coming to see and purchase the collective’s extraordinary creations. A visit to the Inn is a must if only to see the architectural detail and enormous murals in the lobby. Those choosing to stay can enjoy the natural light flooding in through the windows of each mini-suite, adding luster to the wood-lined walls and simple Arts and Crafts furnishings.

Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986, nine of the Roycroft’s original 14 structures including the Inn, Chapel, Print Shop, Furniture Shop and Copper Shop still stand. Of the “guilds” that evolved as centers of craftsmanship during the late 19th century, the Roycroft Campus is the best preserved and most complete complex of buildings remaining in the United States.

The core of the problem

At the other end of the architectural spectrum is the French-inspired Hotel Lafayette in downtown Buffalo. It was designed by Louise Blanchard Bethune, the first professional woman architect in America.

Rocco Termini is one Buffalo native who is determined to bring his city back to life, beginning with the old Hotel Lafayette, designed by America’s first female architect.

Buffalo native Rocco Termini, president of Signature Development, spent millions to restore the Lafayette and other derelict structures. Determined to revitalize the core of the city he loves, he has gone to extraordinary lengths, even helping young chefs to overhaul abandoned buildings and open their own restaurants.

Toutant on Ellicott Street is in one of these beautifully restored buildings. Here, James Roberts cooks the Louisiana cuisine of his youth. “It was terrifying at first. The building was a disaster. We carried out shovels full of needles and filth,” recalls Roberts. “It took two years to renovate, with money going out and nothing coming in.”

Today, Toutant is a thriving restaurant, and a few doors away, Tappo Wine Bar, another Termini success story, features an Italian American menu and moderately priced wines. Nearby is Big Ditch Brewing which opened in 2014, and the following year, launched a menu to accompany their successful line of microbrews.

Indeed, this part of the city center, once virtually a slum, has been reborn as foodie central. “For me, it’s about building a neighborhood,” explains Termini. His ‘If you build it, they will come’ approach was daring. But come they did.

Undoubtedly food has been instrumental in fueling the city’s rebirth. Like Napoleon’s army, a successful city marches on its stomach, and restaurateurs were not slow to recognize the bargains offered by low-priced real estate and a built-in market of both locals and visiting Canadians from just across the border. Buffalo’s restaurant scene has flourished with many young chefs finding a new home amid the city’s revitalization. But despite this culinary evolution, Buffalo will ever be known for its eponymous wings.

Buffalo chicken wings were first introduced in 1964 at the Anchor Bar. Legend has it that Teressa Bellissimo invented the dish out of necessity when the Anchor Bar accidentally received a shipment of wings instead of other chicken parts. She created her own zesty sauce for them and put celery and blue cheese on the side. You have to give her an A+ for ingenuity.

Today, you’ll find wings in virtually every bar in America, though each has its own recipe. In Buffalo, there’s a Wing Trail with about a dozen pubs on the list and an annual Wing Festival in September.

From soap to suds

Food has helped to revitalize another derelict area of the city, aided by another local businessman, Howard Zemsky, who co-chaired the Western New York Regional Economic Development Council.

Larkin Links, a miniature golf course at Larkin Square, features holes designed by different companies or organizations, like The Foundry, a community youth group and H-O Oats, one of Buffalo’s early grain companies that’s now owned by the Seneca Nation.

“Seventy years ago, this was the most vibrant part of Buffalo. Thousands lived and worked here,” Zemsky says, indicating a swath of old buildings once part of the now-defunct Larkin Soap Co. “I wanted to bring it back,” he adds.

Leslie Zemsky, Larkinville’s “Director of Fun,” at Larkinville, organizes her next party in a tiny phone booth filled with photos and posters that purports to be the world’s smallest art gallery.

In Larkin Square, The Filling Station once filled Larkin trucks with gas; now it’s filling hungry office workers with lunch. Nearby is Hydraulic Hearth, a brewpub that serves its own suds along with artisan pizza and offers funky features like the world’s smallest art gallery – in a phone booth.

Perhaps the most significant reason for the success of Larkin Square is the fun-filled ambiance, courtesy of Howard’s wife, Leslie, Larkin’s ‘Director of Fun’. The square buzzes with constant activity like pickleball games, fitness sessions, live music, and free mini golf on a truly unique course, each hole of which was designed by a different local business.

Before Covid, every Tuesday night, 30 food trucks serving everything from meatballs and Pad Thai to ice cream and gooey desserts fed thousands of visitors who come to eat, listen to live music, and buy crafts from local artisans.

“People thought we would implode, but our success has made others more confident,” says Zemsky. Despite the coronavirus, around Larkin Square stores are open, offices are full and other old buildings now are condo developments. The area is now fondly known as Larkinville.

Covid put the food trucks on hiatus but it didn’t stop baseball. Last summer, Buffalo’s hometown team was the Toronto Blue Jays, who moved across Lake Ontario to escape Canada’s cross-border restrictions preventing entry to U.S. clubs. For one glorious summer, Buffalo was again major league. The Blue Jays are gone but Buffalo can still look forward to hockey games between the Toronto Maple Leafs and the hometown Buffalo Sabres.

What do you do with a silo?

Remember those deserted silos and grain elevators? Aspiring mountaineers can now climb the wall of one of those silos. This is just a small part of RiverWorks, a massive redevelopment of the west end of the city beside the Buffalo River. It includes two ice rinks, a 5,000-person concert venue, a zip line, ra oller derby track, four bars and a restaurant. It also features a fully functioning brewery shoehorned into one of the old grain silos. All this has brought a once desolate part of the city back to life.

Buffalo’s city council hasn’t been slow to recognize the importance of revitalization. They decided to honor the city’s history by building a commercial and recreational area at the 1825 terminus of the Erie Canal. Canalside is now the heart revitalization district that includes the Key Bank Centre where the Buffalo Sabres play. Canalside hosts hundreds of events, from concerts to art and craft shows, many of which are free.

In winter, a covered portion of the Erie Canal is converted into a giant (33,000 sq. ft.) skating rink. Can’t skate? Then rent an ice bike, a unique winter experience. During the warm months, craft vendors and food kiosks line the area.

This city saw electricity used for the first time to light an office building and to power a street railway. Here paper was made from pulp for the first time and the first air conditioner was invented. But the city’s history is rivaled by its character and compassion.

Towards the end of last week’s victory over Baltimore that sent the Bills to the championship game, the opposing quarterback suffered a concussion. The people of Buffalo immediately responded by donating more than $407,000 to a Kentucky charity organized by the wounded player that provides food and other essentials to needy children. In a city experiencing rebirth in new and exciting ways it’s clear that its most valuable asset is the spirit and generosity of its people.![]()

Liz Campbell has been a freelance travel and food writer for more than 20 years. Search the EWNS archive to see her articles on Newfoundland, Malta and North America’s Acadian people.