Never Tell A Woman Where She Doesn’t Belong

By Amanda Morris

I love traveling. I love the freedom it gives me to explore the world around me and expand my horizons. I have been fortunate enough to travel alone. The experience provided an element of excitement and also confidence, when I proved to myself that I could venture out on my own. But, in truth I didn’t travel alone at all. My ability to book a flight and explore an unknown destination simply because I desired didn’t develop out of thin air. Rather, it was pioneered by fearless women who fought to break through the wall of societal expectations so future generations could go on their own adventures. These women are central in Jayne Zanglein’s new book, The Girl Explorers, which tells the story of the founding of The Society of Woman Geographers.

Blair Niles was one of the founding members of The Society of Woman Geographers. But her biggest impact may have been the books she wrote about her travels. Niles was cognizant of the troubles of all people, a rarity in the time when many supported segregation and eugenics. “Blair loved to meet people in their native lands, especially aboriginal people,” Zangelin writes. Niles herself is quoted as saying, “Here is living history… their dress, habits, customs, described in the school textbooks right before my eyes. I am fascinated by this primitive way of living here in the 20th century.”

Niles used her voice to tell those people’s stories. While traveling to French Guiana, she became fascinated with the unjust prison system and decided to write prisoners’ stories in a way that masked their identity. In order to understand the perils encountered by a prisoner trying to escape the thick jungle of the remote island where they were kept, she decided to try it for herself. Niles discovered the jungle was “perpetually vigilant” filled with fire ants, mosquitos, and vampire bats and that death waited at every turn. She later wondered if a prison-weary man is, “Ready for the terror of its vastness? Do they realize that the guards drowse in the shade of their bread-fruit trees confident that the jungle is playing its part in the relentless game of checkmate?”

The result was Condemned to Devil’s Island, the fictionalized stories of the prisoners she met. And people read it. More importantly, the right people read it and soon after a Salvation Army Camp was set up to monitor the conditions and ensure prisoners were treated humanely. Nile’s travels made such a thing possible. She had the thirst and drive for great adventure and after achieving them she helped make the places she traveled a little bit better for those who remained.

Attending Belgian wounded in 1915 is a nurse creadibly believed to be Ellen La Motte

When the Society of Woman Geographers was founded in 1925, World War I was still a bright stain in the American psyche. It was a conflict that required much more of its citizens than past wars. As such many of the founding members of the Society had ties to the war, including Ellen La Motte. La Motte did not travel for leisure. When she traveled to Europe she went as a skilled nurse to help wounded soldiers. Her motives were vastly different from the other nurses deemed by La Motte to be superficial society girls looking for something exciting to talk about at dinner parties. Throughout her service, she recorded the devasting realities of war. As she was transferring from one hospital to another closer to the frontlines, she stopped in Dunkirk where the Germans dropped a bomb close to the hotel as she slept. She experienced several more vicious attacks. While taking refuge in a cellar as bullets reigned down, she witnessed a man crazed with fear put a bullet through his mouth.

Unlike her counterparts, La Motte’s travel writing contains little sense of beauty or wonder. Her stories avoid the glamorous side of travel and have few of the Instagram elements now de riguer in Influencer travel blogs. Sometimes travel is about duty and occasionally that responsibility leads you on an adventure to a place or situation you never thought you’d be. And really? Isn’t that part of why we travel? To be changed—albeit by far less gruesome means. Ellen’s writings were considered the first realistic view into what war is like. A reviewer for the Los Angeles Times once said that eight of the ten best war stories are authored by La Motte.

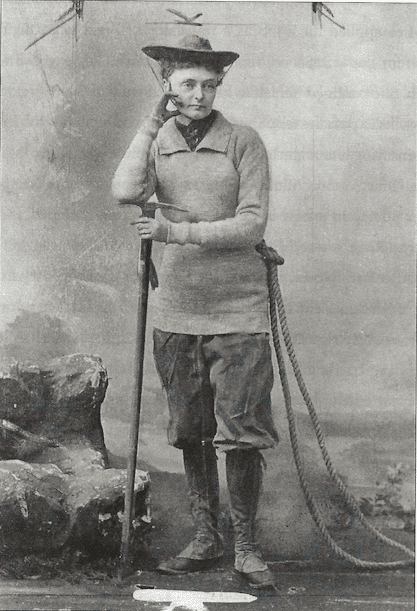

Annie Smith Peck was one of my favorite women to read about because she was so different from many of the women in the Society. Peck would go onto become one of the most accomplished mountaineers of her time. At age 58 she reached the summit of Peru’s Mounnt Huascará, one of the tallest peaks in the Western hemisphere at over 20,000 feet. The northern peak of the mountain would eventually be renamed in her honor. But interestingly, she did not begin climbing until she was 45 years old. That’s when she first saw the Matterhorn and was “seized with an irresistible longing to attain its summit.” It wasn’t an easy task for anyone, let alone an inexperienced climber, but she would not be deterred. She practiced for several years in the mountains of New Hampshire and California before she became the third woman in history to ascend the Matterhorn.

Annie Peck (1911) in her mountain climbing gear

Peck is quite ambivalent in her memories of the experience. She referred to the most dangerous section of the ascent that had claimed the lives of earlier climbers as her favorite part due to the ropes left behind. Neither was she worried by the idea of a night climb, declaring she “saw nothing in the least alarming” about the fact that you could see drops thousands of feet deep to either side. Her friend compared her desire to climb to a suicide mission but Peck was unbothered. She did what she wanted, ignoring the scoffs of those around her, especially when the media focused far more on her outfit, which included pants rather a society appropriate skirt. Peck had a goal and would not stop until she achieved it. It was as simple as that.

How could I never have heard the story of Marguerite Harrison before I read this book? Harrison lived an exceptionally colorful life and held a variety of groundbreaking roles. She first served as an assistant society editor for the Baltimore Sun, assigned to write about women’s contributions to the war. But that was not enough for Harrison who wanted to go to Europe as a reporter. Her editors turned her down, citing that she was a widow with a teenage son. Harrison persisted and contacted the head of Army’s Military Intelligence Division offering to become a spy. She could speak multiple languages including French and German, she noted matter of factly, adding that she could easily pass as a French woman should the situation arise. The man who interviewed her agreed, remarking that she was fearless and more than capable of deceiving the average person.

Thus, just after the end of World War I, Marguerite Harrison began to spy on the Soviet Communist Party. Once in Russia, she embedded herself into the political scene, attended a lecture by Lenin and interviewed Trotsky. It was not a seamless transition, however. To achieve this goal, Harrison said she “made myself absolutely sexless and impersonal, partly as a measure of self-protection in an atmosphere fraught with dangers.” Despite how careful she thought she was, she was eventually arrested and taken to Lubyanka Prison. In exchange for her release, she agreed to spy for the Soviets.

Or so they thought. Harrison secretly got word to her family who alerted Washington which happily turned her into a counter spy. Harrison continued to deceive the Soviets from the guest house Moscow provided her in exchange for her work as a counter spy. Eventually, they caught on and imprisoned her once again. After ten months, she was released back to the United States where she wrote her book, Marooned in Moscow.

Marguerite Harrison with Bakhtiari men (ca. 1924)

One afternoon in the winter of 1925 Blair Niles met Marguerite Harrison for afternoon tea. Both were developing new narrative styles: Blair concentrated on travel writing that emphasized people rather than places while Marguerite was pioneering the ethnographic documentary. Harrison thought the migration of a nomadic Bakhtiari tribe in Persia would make a compelling story so for seven weeks she accompanied 50,000 Bakhtiari as they guided their livestock across six mountain ranges and the swirling Karun River to winter pasture. The result: Grass: A Nation’s Struggle for Life. It was the second ethnographic film ever produced, the first being Nanook of the North.

The Society of Woman Geographers was founded in 1925 as a reaction to the refusal of the Explorers Club to admit women members, a practice it continued until 1981. The practice of denying entry to women was explained in 1932 by Explorers Club president, Roy Chapman Andrews, who said in a speech to the female student body of Barnard College that “Women are not adapted to exploration.”

Jayne Zanglein’s The Girl Explorers shows the folly of Andrew’s words by detailing the exploits of Pearl Buck, Amelia Earhart, Margaret Mead, Jane Goodall and a dozen other world travelers who challenged gender norms and sought out amazing adventures in remote parts of the world the likes of which their sex had never seen before. They were the first in many cases, but luckily for women everywhere, they were not the last.

Zanglein does a great job of telling these stories in a variety of different ways in terms of length while also using impactful quotes, often times by the Society members themselves, at the start of each chapter to set the tone and get the reader into the right mindset. She also makes good use of biographical background to create a sense of intimacy, context and direction.

The book has an impressive number of photos that serve to bring the audience further in and create a sense of kinship between the modern reader and these women who lived and traveled a century ago. Famed pilot Amelia Earhart, a Society member and the first recipient of their Gold Medal Award, features in many of the photos smiling along with the other women at a dinner celebrating the 10th anniversary of the founding. However, for all the details this book contains in terms of content, as well as a selected bibliography and list of abbreviations, the lack of index becomes more than a bit vexing. The absence makes it difficult to fit all the personalities into a narrative timeline.

This book comes amid a resurgence of interest, publications and events relating to the Society of Woman Geographers. They include the Margaret Mead Film Festival and a feature length documentary telling the story of Society member Te Ata Fisher.

The phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants” is not new. As a female traveler, I stand on the shoulders of these amazing women who came before me that cleared the path so that I can jump on a flight and go without hesitation. I am endlessly grateful for them. But here’s the thing: up until I read this book, I didn’t know the names of the people I had to thank. Now I do. So, thank you Society of Woman Geographers, I couldn’t do it without you.

The phrase “standing on the shoulders of giants” is not new. As a female traveler, I stand on the shoulders of these amazing women who came before me that cleared the path so that I can jump on a flight and go without hesitation. I am endlessly grateful for them. But here’s the thing: up until I read this book, I didn’t know the names of the people I had to thank. Now I do. So, thank you Society of Woman Geographers, I couldn’t do it without you.![]()

Amanda Morris is a junior at Syracuse University, pursuing a degree in Television, Radio, and Film at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications.