Photographer Dirck Halstead keeps flies off the blood covering war correspondent David DeVoss. Photo by Le Minh Thai

By David DeVoss

The day I almost died was a sunny Sunday 50 years ago this week. I was a 24-year-old Time Magazine correspondent in Saigon. Along with photographers Dirck Halstead and LeMinh Thai, I decided to get an early start on the week by driving north up Highway 13 to meet a company of South Vietnamese marines. Their goal: March to the Cambodian border and lift the siege of An Loc, a tiny rubber town founded by the French that had been encircled by the Viet Cong for three months.

The week before Halstead and I had driven to Long Binh, a sprawling US army base an hour outside Saigon, to meet the American general in charge of resupplying the outpost by helicopter. He vowed the coming offensive would trap the VC like “rats in a haystack.”

Waiting for the medevac beside Vietnam’s Highway 13. Photo by Dirck Halstead

The general was leaving momentarily to reconnoiter the town by air and his adjutant, a young captain from Texas A&M in spit-shined Aggie boots with spurs, offered one of us a seat on the chopper. Who should go? We couldn’t agree. “We’ll see you inside An Loc once the Vietnamese punch through,” I smiled, knowing the coming battle had all the elements of a great story.

The road to An Loc crossed a barren plain that offered only shell craters for cover. But on the day of the attack nobody was worried since a B-52 strike scheduled for precisely 11:59 am would eliminate any communists hiding in the scrub. At the appointed hour the bombs silently fell and the land erupted into billowing clouds of dust that made clear why B-52 bombings were described as “Rolling Thunder.” Moments later we slowly began to advance alongside the surrounding tanks.

Flanked by two Vietnamese marines, I walked forward, simultaneously trying to take notes and pictures, when suddenly my world exploded. When I emerged from the void I was blind, deaf and unable to move. I knew I was alive when I felt my university ring and wristwatch being stripped from my arm, so I offered up a prayer: “Please, God, don’t let me be run over by a tank.”

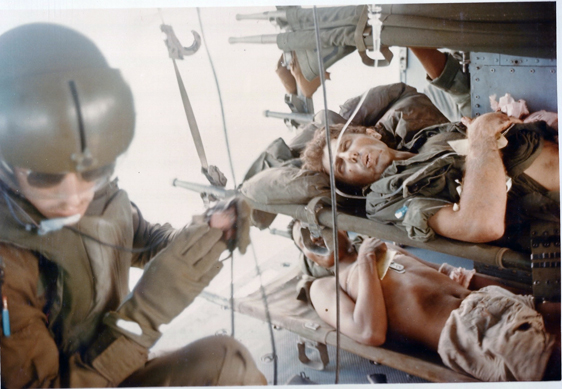

Time correspondent David DeVoss medevaced to the Third Field Hospital in Saigon with extensive shrapnel wounds. Photo by Dirck Halstead

Once the tanks rumbled past, I was carried to the highway where a medic inserted an IV while Halstead swatted away flies. “Buddy, if you live you’ll owe your life to that flak jacket,” said a disembodied voice I later learned belonged to a US advisor who literally saved my life by calling in a medevac.

I have no memory of being helicoptered to the Third Field Hospital in Saigon, where I had two operations to remove mortar shrapnel and shattered bone fragments. I do remember waking up ravenous and calling LeMinh who drove to the hospital with mangos and sticky rice drenched in coconut cream.

“I don’t how this could have happened,” I told LeMinh between bites of mango. “I was wearing a St. Christopher’s medal and even had a Chai pendant from a Jewish girl in Detroit.” LeMinh just stood there, incredulous.

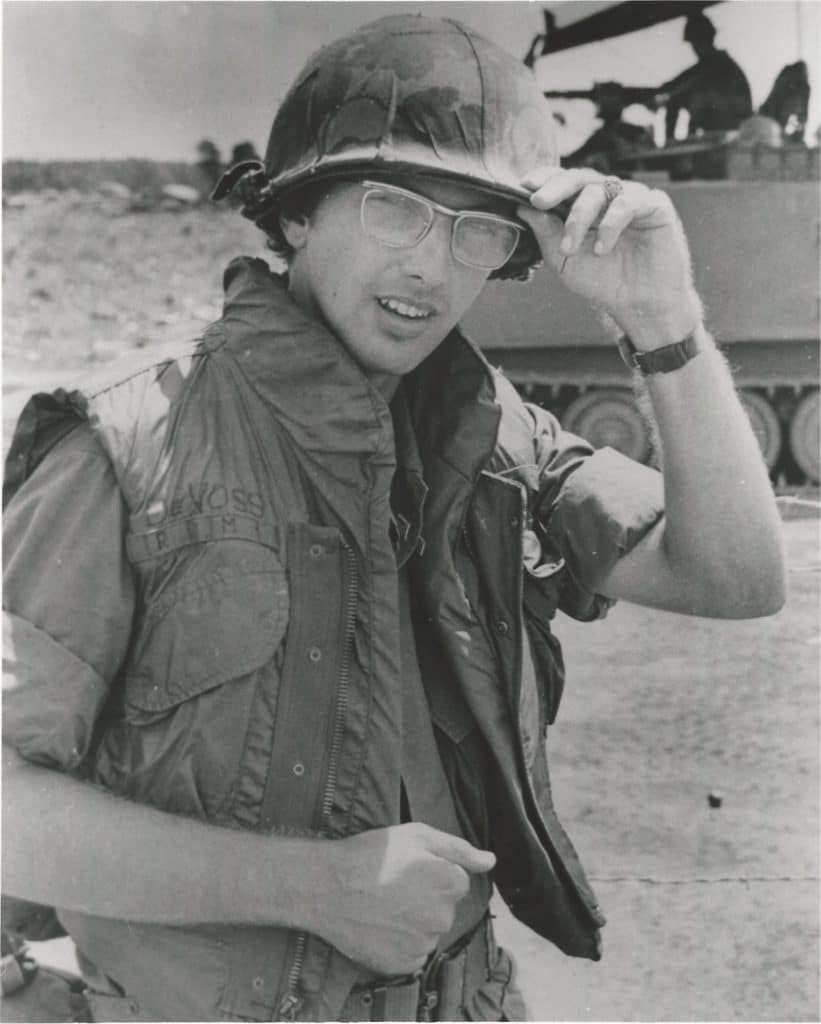

Interviewing a U.S. Advisor along Highway 13 two days before the attempt to lift the siege of An Loc. Photo by Le Minh Thai.

“Those things don’t work in Vietnam,” he explained with a smile. “Only Lord Buddha can protect you here.”

North Vietnam’s Easter Offensive was entering its fifth week and the hospital was so short of space that casualties constantly were moved between wards. One morning I was wheeled into a room of injured Korean soldiers from Binh Dinh province who, despite their wounds, were doing chin ups on water pipes hanging from the ceiling. Though entertaining, the highlight of the day was the arrival of the Donut Dollies, young Red Cross volunteers dispensing flirtatious smiles instead of pastry.

Several days later, I was placed on a “Nightingale” hospital plane full of soldiers. The plane stopped at Clark AFB in the Philippines where I learned that I was the only Wounded in Action passenger. All the soldiers were addicts or suffering from self-inflicted wounds.

Time was paying the medical bill and offered to send me to Walter Reed or a military hospital in San Antonio. But just wanting to return home I decided to go to Methodist Hospital in the Oak Cliff section of Dallas.

The U.S. military officially “furled the flag” in 1973, but American soldiers continued to accompany South Vietnamese units unofficially. Here DeVoss talks with a U.S. advisor assigned to provide air support for the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Photo by Le Minh Thai

“So, what brings you here,” the admitting nurse asked while flipping through papers on a clip board. “Mortar shrapnel,” I responded, to which the nurse replied, “Shrapnel? What’s that?”

Ten months and three more operations later I returned to Vietnam. But it was not until 1982 – seven years after the end of the war and ten years after the day I almost died – that Dirck Halstead and I finally made it to An Loc on a reporting trip for Time. The area had changed hands several times before the end of the war and the road into town was lined with dozens of grave markers each bearing a solitary Viet Cong star and the words Liet Si or “Revolutionary Martyr.”

Americans killed in action were flown home to their families for dignified burial. Fallen South Vietnamese were taken to formal government cemeteries. Viet Cong (VC) and soldiers from North Vietnam (NVA) were buried where they fell. These and other graves of Liet Si or “Revolutionary Martyrs lined the highway heading into An Loc in 1982. Photo by David DeVoss

The town itself was desolate, impoverished and suffused with despair. There were no structures suggestive of French culture. “How could so many people have died for this place?” I wondered as Halstead and I walked past a panting goat laying prostrate near a mound of dried feces.

My escort from the Vietnamese foreign ministry in Hanoi ran off to find the mayor, who appeared shortly, seemingly aroused from a nap. There were no words of welcome.

“What are you doing here?” the young but grizzled man asked. I proceeded to tell him why it had taken me so long to get to An Loc. He glowered.

“I remember that day,” he said dryly.

“You were there?” I smiled, not thinking of the implications. And so we discussed the day of my abortive entry; me asking how he could have survived a B-52 strike, him explaining how the VC dug slanted foxholes to minimize the concussion. I asked if he remembered three men marching between the tanks toward An Loc.

“Of course, he smiled, “I fired on them.

“Well, your mortars killed two of them,” I responded. “But I survived.”

After the translation was complete we stared at each other in the sweltering heat. Seconds passed. Finally, the former Viet Cong leaned forward and glared, “I wish I had killed you.”

Before leaving An Loc, Time correspondent David DeVoss and photographer Dirck Halstead were shown around the town by a local official more welcoming than the mayor. Photo by Tran Ngoc Thach

And there we sat in the mephitic haze of an earthly Hell; me in shock, him radiating hatred.

I had expected the faux camaraderie old adversaries exhibit when unexpectedly confronting a foe from the past. After all, his side won. I was the one gimping around with a lifelong limp. But then I remembered the cavalcade of graves leading up to this outpost of despair. How bitter his victory must taste.

“I’m sorry you feel that way,” I said rising to leave. “But you’ll understand that I’m glad you didn’t”

We parted without shaking hands.

David DeVoss, Vietnam, 1972