St. Nicholas icons come in an array of sizes and prices at a Patara museum gift shop; the saint was born in this long-ago Lycia capital. Photo by Mary Bergin.

By Mary Bergin

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus, but the original St. Nicholas was very different from what we know today.

His home was on the Mediterranean Sea, not the North Pole. More pious than jolly. Wearing a cleric’s miter hat, not a festive stocking cap.

For much of the world, St. Nicholas magically and faithfully delivers little treats to children on Dec. 6 – St. Nick’s Day, a prelude to the bigger haul of gifts that he’ll leave after sliding down chimneys on Christmas Eve. An army of stout surrogates with bushy white beards and belted red suits mimic and commercialize the jovial old man, known for working wonders of mythical proportions with elves and reindeer from his Arctic workshop.

Also known as Sinterklaas, Kris Kringle and Father Christmas, he is a far cry from the real person behind the folklore, Nicholas of Myra, born in southwest Türkiye during the 3rd century and orphaned when an epidemic reportedly killed his parents. His Christian family was wealthy, and Nicholas (pronounced NICK-o-lie in Türkiye) reportedly used his inheritance to help the destitute and debilitated. He earned a reputation for generosity, entered the priesthood and in the 4th century was anointed Bishop of Myra.

“Some legends say he tossed bags of gold through an open window or down the chimney, where they landed in stockings or shoes that were drying by the fire. Many believe this was the inspiration for the tradition of the Christmas stocking,” writes the St. Nicholas Center, which is devoted to the saint and based in Holland, Michigan.

There are myriad reasons to visit the homeland of St. Nicholas in what is now the Muslim country of Türkiye, even though his roots have little to do with Christmas.

Land of the Lycians

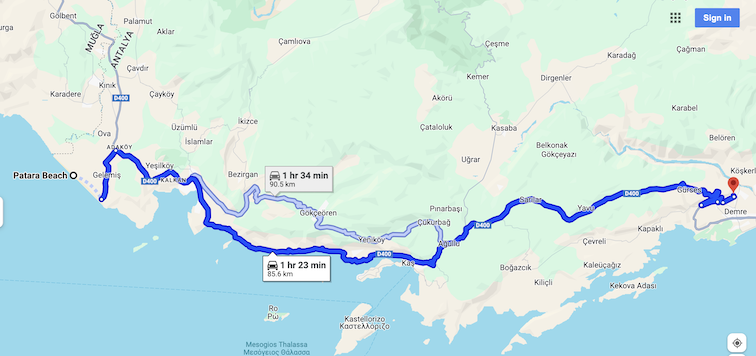

Roughly 50 scenic miles in Asia Minor separate the Turkish seaport city of Patara, where Nicholas was born, and Myra, where he was buried. Nearly all of the route – along D400 – is part of Türkiye’s 600-mile Turquoise Coast. (The name is a nod to the Mediterranean Sea’s glorious hue). The drive – especially riveting at sunset – is a stunning mix of steep outcroppings, forested terrain and farmland. It is full of hairpin turns that shadow the shoreline and navigate the Taurus Mountains.

The highway from Patara, where St. Nicholas was born, to Myra, where he served as bishop and is buried, runs along Tükiye’s Turquoise Coast. Luxury yachts are anchored around the coastal inlets and islands. Most belong to families of Russian oligarchs who are sheltering assets or avoiding service in Ukraine.

Also known as the Turkish Riviera, this is where the rich and famous come to anchor yachts and linger along widespread beaches. History and archeology buffs roam significant and numerous ancient ruins; ongoing government work identifies, excavates and preserves new sites too. Serious bikers and hikers follow the Lycian Way, 435 miles of former roads, mule trails and footpaths between Fethiye and Antalya. British trekker Kate Clow in 1999 took the initiative to organize, mark and market the trail; in 2012 she helped establish the Cultural Routes Society to protect this project and others.

What is known today as Teke Peninsula was the Lycia region in ancient times, an area that bounced from Greek to Roman to Byzantine rule. Parts of the Lycian Way are still used by shepherds who seasonally guide flocks of sheep between mountains and lowlands. The overall passage ranks among the world’s best walks because of the scenery and sights, but it is not as well-known as, say, Spain’s Camino de Santiago.

Remarkable Ruins

Roman-era ruins are plentiful in Lycia, and that includes Xanthos and Letoon, neighboring settlements that together are one of 21 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Türkiye.

On their way to similar status are the ruins of several Lycian cities, which include Patara, and St. Nicholas Church, constructed for the Bishop of Myra in the 4th century.

Architectural remnants from multiple eras increase the significance and intrigue of Patara, Lycia’s former capital. There are Roman-built roads with arches and pillars, Byzantine basilicas and baths, a Greek amphitheater and Lycian stone coffins in what is now a national park with beach and forest.

Repairs to Patara’s parliament building were completed in 2011. When restoration of the dead city’s 64 AD lighthouse is finished, the beacon will be among the oldest in the world that is still standing.

Nearby is Gelemis, whose population hovers just under 1,000. Restaurants, shops and pension lodging in the form of family-run guesthouses quadruple that total during the peak of tourism from May to October.

All this – plus ongoing environmental efforts to protect sea turtles along Patara Beach, which at 11 miles is the longest white-sand beach in Türkiye – makes Nicholas’ birthplace of Patara seem more like a recreation destination than a memorial to an orphan who became a beloved saint. But Nicholas is not ignored. In the Patara park’s gift shop are numerous religious icons depicting St. Nicholas at different points in his life – but never as the stereotypical Santa.

Fertile Offerings

Among the ruins of Myra is an open-air museum best known for often-intricate tombs cut into rocky cliffs and a Roman theater that could seat 11,000 during the 5th century BC.

Dominating the ruins of Myra are intricate tombs that were cut into rocky cliffs. Photo by David DeVoss.

A small set of shops sells souvenirs: scarves and shawls, pottery and onyx, coffee and tea sets, Turkish coffee and sweets, fine jewelry and kitsch. Stray but healthy-looking cats roam, nap and flirt as they famously do elsewhere in Türkiye.

Circling the ruins are hundreds of back-to-back greenhouses that fill the valley and extend toward the sea. Our guide says we’re seeing only 1 or 2 percent of Myra; the rest is under these indoor gardens that grow tomatoes, cucumbers, eggplant and other vegetables all year. Outdoors there are citrus and pomegranate trees, rows of tea plants and forests of strawberries.

Even the area’s ancient name acknowledges nature: “Myra” is an offshoot of “myrrh,” the thorny tree whose sap is considered medicinal because of antioxidants that are purported to soothe arthritis, inflammation, neuropathy.

The modern-day community of Demre is a St. Nicholas pilgrimage point. It is a farming town one mile south of the ruins.

Myths and Realities

Anchoring St. Nicholas Museum in Demre is the small St. Nicholas Church, prone to flooding as it’s three feet below sea level. Restoration of the church, its murals and mosaics were completed in 2023.

Our guide described Nicholas as the most respected individual in the Greek Orthodox Church after Jesus and Mary. Scholars still debate what was real vs. embellished as Nicholas morphed from privileged child to orphan, generous soul, bishop, saint and pop icon.

The saint’s tomb remains inside of the Church of St. Nicholas, but his bodily remains rest in two churches in Italy. Photo by Mary Bergin.

Nicholas is known as the protector of sailors, women and children in southwest Türkiye. One of the often-retold tales: He gave bags of gold to three poor girls, so they had dowries to attract husbands and avoid lives of prostitution.

St. Nicholas Day is Dec. 6 here too, but the observation is all about solemn worship because that’s when the bishop died in 343 AD. The date coincides with the start of Poseidon months, a time to pray for the safety and prosperity of those who work at sea.

After Nicholas’ death, the faithful would flock to his tomb at the Demre church. That still happens, although his bones are likely no longer there. During an 11th Century upheaval of the Byzantine Empire, the remains reportedly were transported to Bari and Venice, Italy. Each city built a church in the saint’s honor, but other reports suggest that – like the spirit of Santa – physical remains might be more widespread.

Cultural Spins

The only sculpture of St. Nicholas in Demre until 2000 was this one, made of bronze. Photo by Mary Bergin.

Families in Türkiye are much more likely to celebrate the beginning of a new year, not Christmas, but local and national governments recognize and respect the worldwide influence of their native son.

In Demre, bits of controversy have sprouted. Statues depict Nicholas as a gift giver, but his appearance has changed with the times.

In the church garden stands a bronze St. Nick in a hooded robe, toting a gift bag and surrounded by children. It was the only sculpture of him in Demre until 2000, when a new bronze statue showed Nicholas as a bishop who stood atop a globe.

Five years later, a sturdy plastic version of Nicholas was introduced, strongly resembling a colorful, modern-day, bell-ringing Santa Claus. That turned out to be a contentious move that drew disdain.

Since 2008, a fiberglass and toned-down version of St. Nicholas is one of the first things visitors see when approaching the historic church; the statue is of a Turkish man with two children who are holding gifts.

What happened to the previous Santa? He’s hard to miss, across the street and in front of a big souvenir shop.

Since 2008, this Turkish version of St. Nicholas is one of the first things visitors see when approaching the historic church in Demre. Photo by Mary Bergin.

For more Information

Because of the difficult pronunciation of its language and sometimes remote locations of ruins, Türkiye is best explored with a qualified guide. For ideas, consult https://turkeytravelplanner.com and https://goturkiye.com.

Mary Bergin of Madison, Wis., got acquainted with southwest Türkiye after the announcement in Istanbul of her fifth Lowell Thomas Award for excellence in travel journalism. Her recent stories for East-West News described the booming business in ocean-going condominiums and the European heritage of the American Midwest.