By David DeVoss

When California architect Robert Steinberg opened an office in Shanghai twelve years ago, he felt as if he had arrived at the leading edge of the Chinese Century. Unlike America, where architects were being laid off and signature buildings scaled back, the biggest city in the world’s most populous country was developing at a rate unprecedented in human history. “We talk acres in America; developers here think kilometers,” Steinberg explained, as he walked through offices still packed with employees despite the late evening hour. “It’s as if this city is making up for all the decades lost to civil war and communist revolution.”

But Steinberg admits he never really understood Shanghai until the night he dined with several prospective clients. “I was trying to make polite conversation and started discussing some political controversy that seemed important at the time,” he remembers, “when one of the businessmen leaned over and cautioned, ‘We’re from Shanghai. We only care about money. You want to talk politics, go to Beijing.”

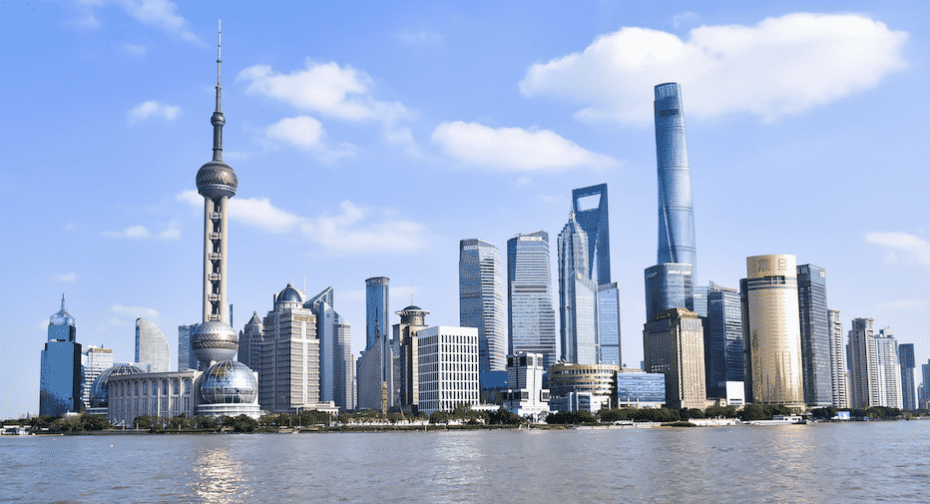

Great cities of the world are tangible expressions of wealth and power. Nineteenth century London reflected the mercantile wealth created by Britain’s industrial revolution and colonial empire. New York was the center of 20th century commerce and culture thanks to America’s victory in two world wars, neither of which touched its shores. Today, Shanghai is poised to become the premier city of the 21st century.

With a population of 27,100,000, Shanghai is the economic engine powering the world’s most rapidly developing country. At a time when North America and Europe still are struggling with economies enfeebled by the coronavirus, Shanghai’s GDP – equal to half of the total economy of India – is growing at 6% a year. More than 300 foreign multinational companies have established regional headquarters there. Today, Shanghai has the largest concentration of skyscrapers in the world and a population density four times that of New York. But what makes the city truly unique is that while resolutely embracing the future Shanghai continues to revere its past.

I arrived in Shanghai aboard a bullet-shaped maglev train that made the 19-mile trip from the airport in less than seven minutes. During my last trip to the city 16 years before Shanghai was holding a global architectural competition to come up with a master plan for the development of Pudong, the largely undeveloped 200-sq. mile agricultural part of the city east of the Huangpu River. The focus of the competition pitting four of the world’s leading architects was Lujiazui, a mile square riverside mudflat China vowed to transform into Asia’s premier financial, commercial and trade center by the year 2020. “Shanghai will be the head of an “enormous dragon of wealth” that will extend from the mouth of the Yangtze River far into China’s vast interior, vowed Communist party leader Deng Xiaoping.

Shanghai lost no time in implementing Deng’s vision. By the start of the new millennium the city had amassed the largest concentration of skyscrapers in the world. Half of the world’s construction cranes twirled atop future hotels and office buildings. By 2010, Shanghai and several other cities were developing so rapidly that half of the world’s concrete and a third of its steel were being used on Chinese construction projects.

Shanghai’s Nanjing Road is the busiest pedestrian walkway in Asia. These Sunday afternoon shoppers keep the street crowded into well into the following morning. Photo by David DeVoss

As I rocketed toward Shanghai at 268 mph all of the bean fields were gone. In their place stood a constantly morphing metroplex of clustered skyscrapers and terraced apartments separated by wide, tree-lined boulevards all zooming past in a cinematic blur.

My destination was the Jinmao Tower, a 1,381 ft. high art deco pagoda whose tapering segments reminiscent of bamboo are reinforced by steel bands that form a surreal exoskeleton. Inside the Jinmao sits the Grand Hyatt. The hotel has a “sky pool” on the 57th floor where people literally can swim in the clouds, but it’s the 88th floor observation deck that offers the best view of hundreds of post-modern office spires poking through the cumulous blanket.

If architecture reflects a city’s wealth, imagination and faith in the future, Shanghai clearly has arrived. From the top of the Jinmao, I had to look up to see the top of the World Financial Center. Closer to the river stands the Bank of China, a glass-curtained structure whose exterior seems to twist out of a splayed sheath like a tube of lipstick. Two rampant parallelograms comprise the nearby Bocom Financial Towers, a favorite of Hollywood directors making action movies because of the buildings’ juxtaposed angles. In the distance, squatting like a coiled spring on the western, or Puxi side of the Huangpu, stood the Nanpu Bridge, a five-mile spiral of concrete that corkscrews high into the air before heading across the river. “Pudong is the Dragon’s Head,” a Shanghai economist had told me during my last visit. “And when the head moves forward the whole body advances.”

The atrium of the Grand Hyatt Hotel inside the 88-floor Jinmao Tower in Pudong. Photo by David DeVoss

Although a fishing village called Shang Hai existed as early as 1291, the modern city did not begin to grow until after the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing when it was claimed by the British following China’s defeat in the first Opium War. Of the five “treaty ports” ceded by the Qing emperor, Shanghai had the most potential. Unlike the existing southern trading centers of Canton and Macau, Shanghai was not subject to typhoons or tropical disease. Neither was it plagued by Beijing’s freezing winters and Gobi Desert dust storms. What it had was the perfect location – just 14 miles up a navigable tributary from the mouth of the Yangtze River, which carried the vast majority of China’s trade in tea, silk and ceramics.

The most valuable cargo traveling up the Yangtze was opium, or foreign mud. By the time the British arrived in Shanghai in November 1843 one out of every ten Chinese was addicted. If Shanghai had a spiritual founding father it probably was William Jardine, a Scottish opium trader nicknamed “Iron-headed Old Rat” because he stoically withstood assault by a Cantonese mandarin while attempting to deliver a free trade petition. Jardine and his partner James Matheson controlled a third of China’s opium trade and were the prime beneficiaries of extraterritoriality, an imperialist construct that made the treaty ports autonomous oligarchies.

Jardine was an ardent supporter of the opium trade, describing it as “the safest and most gentleman-like speculation I am aware of.” He later used his enormous wealth to buy a seat in parliament, but his money could not buy respectability. In his novel Sybil, British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli mocked Jardine, whose character he named Mr. Druggy, as “a dreadful man…with a million in opium in each pocket, denouncing corruption and bellowing free trade.”

Time lapse image of Shanghai’s historic Bund, a stretch of colonial office buildings and clubs along the Huangpu River. The clock tower the British called Big Ben now is nicknamed “Big Ching.” The marble and granite buildings were built to convey power and permanence. Photo by George Liu

The right to sell opium with impunity made Shanghai a magnet for “free trade adventurers.” American merchants began arriving in 1844 and soon were followed by French, German, Japanese and Jewish financiers from Baghdad fleeing Ottoman hegemony. Ignoring the old walled Chinese city, they staked out an International Settlement west of the Huangpu River along the Bund, or embankment. The presence of foreigners and the special privileges they enjoyed enraged Chinese who in 1853 and again in1860 mounted violent insurrections against the Qing Dynasty and the unequal treaties it had signed. The only effect of the rebellions, however, was to drive 300,000 Chinese refugees into the International Settlement, giving Shanghai a permanent Chinese majority and making it the fastest growing city in the world.

By 1857, the amount of opium passing through Shanghai had quadrupled, but even better days lay just ahead. When the U.S. Navy blockade cut Europe off from Confederate cotton, Shanghai merchants joined forces with Yangtze peasants and began supplying English textile mills with cotton. The new trade route temporarily made cotton Shanghai’s leading export commodity, quashed a tentative British plan to enter the war on the side of the South and earned the gratitude of Gen. Ulysses Grant, who following his presidency personally came to thank the city in 1879 for its role in preserving America’s union.

The robust economy brought little unity to Shanghai’s ethnic mix. Insisting on a more traditional colonial stricture, French residents formed their own concession between the International Settlement and the Chinese walled city and began filling it with Gallic bistros, boulangeries and tranquil residential neighborhoods filled with gracious villas. In contrast to “Frenchtown,” the International Settlement remained an Anglophone oligarchy centered around the municipal racecourse, emporia-studded Nanjing Road and Bubbling Well Road, whose leafy precincts were dominated by Tudor and Edwardian mansions occupied by British taipans and their Chinese compradors. Each of the city’s three sections was administered as if it were a separate country with its own laws, police force, utilities and electrical voltage. Street names and the sequence of numbered addresses changed when leaving one concession and entering another.

But the real center of Shanghai was, and is, the Bund, an eight-block long stretch of banks, insurance companies and municipal buildings that for more than a century reigned as the most famous skyline east of Suez. Bookended by the British consulate and the Shanghai Club, where taipans and young “griffins” out to make their fortune sat in descending rank along a 110-ft. long bar, the Bund was built to evoke power and permanence. Clad in granite and marble, its buildings are a jumble of architectural styles festooned with balustrades, cupolas Doric columns and domes. A Beaux Arts Customs House erected midway down the street is topped with a 300-ft. bell tower resembling Big Ben. Nicknamed “Big Ching,” it struck the Westminster chime on the quarter hour for more than half a century. Nearby stands the massive Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank building, whose front entrance is guarded by two life-sized bronze lions, one roaring to emphasize power, the other at rest to symbolize protection.

Early most mornings women gather in a small park across the street from the Bund to exercise in the cool air blowing off the Huangpu River. Photo by Adli Wahid

It did not take customers long to realize that behind the Bund’s imperial facade most of the work was being done by Chinese. “Even in such lordly institutions as the British banks on the Bund it seems impossible to transact even such a simple affair as cashing a cheque without calling in the aid of a richly-dressed Chinese,” noted Victorian travel writer Isabella Bird. Ninety percent of the Chinese living in Shanghai were migrants in 1885. By 1912, when the Qing Dynasty was replaced by Sun Yat-sen’s Republic of China, Shanghai was the sixth largest city in the world with a population over five million.

Chinese objections to western privilege did not prevent them from taking advantage of Shanghai’s sybaritic lifestyle. Confucian values eroded so quickly that Cantonese traders, no strangers themselves to cunning and guile, joked that “a man from Shanghai would rather put oil on his head than on his food.”

If wealth shaped Shanghai’s architecture, vice defined its society. As to be expected in a city founded on opium, gambling and extraterritoriality, worldly pleasure was easy to find. The top tier of the “flower world” consisted of courtesans with bound feet who wore cheongsams slit to the hip and were carried between assignations in palanquins. Considered stars of the erotic arts, “singsong girls” frequented clubs with names like Temple of Supreme Happiness and Garden of Perfumed Flowers where they were courted by wealthy patrons who occasionally elevated them to the status of concubine.

At the bottom of the economic scale were opium dens called “swallows nests” and the flower and smoke rooms along Blood Alley, where an inebriated seaman on shore leave risked being Shanghaied if he ventured out on the Huangpu River in a flower boat belonging to a “saltwater sister.”

Nearly all of China’s Buddhist temples and pagodas lay in ruins after the Cultural Revolution. China’s communist government considers religion to be a social evil but rebuilt them anyway, reasoning that Buddhist temples were sites foreign tourists expected to see. Shanghainese rarely patronize their temples. elderly folks from the countryside serve as costumed attendants and monks. But tourists seeking that perfect Instagram shot seem to like the ambiance.

All the gambling and guiltless sex was an affront to American missionaries, like Elijah Bridgeman, who blamed the licentiousness on Shanghai’s Chinese, not their western paramours. He urged his Christian brethren to raise an evangelical army to redeem the Sodom and Gomorrah of the Far East. “The minds of this people must be remolded and their manners reformed for as yet they are but half civilized,” he wrote in China Repository, a magazine for Protestant missionaries.

Though they came to China in vast numbers, the missionaries didn’t have a prayer. By 1935, one out of every 13 women in Shanghai was a prostitute, causing local wags to joke that the two male lions in front of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank only roared when a virgin passed.

Rectitude’s greatest challenge was the Great World, a five-story entertainment complex packed with marriage brokers, magicians, earwax extractors, love letter writers and casino croupiers. “When I entered the hot stream of humanity, there was no turning back had I wanted to,” wrote Austrian-American film director Joseph von Sternberg in his autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry. “The fifth floor featured girls whose dresses were slit to the armpits, a stuffed whale, story tellers, a mirror maze and a temple filled with ferocious gods and joss sticks.” Sternberg returned to Los Angeles after his visit and made Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich who at one point smolders, “It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.”

Great World Amusement Complex under renovation. Photo by David DeVoss

While the rest of the world suffered through the global Depression, Shanghai – by now the world’s fifth largest city – sailed blissfully along. A 1935 Fortune magazine article noted “the orgy of building, the fantastic piling of wealth upon wealth that came to Shanghai during the depression….If, at any time during the Coolidge prosperity,” Fortune continued, “you had taken your money out of American stocks and transferred it to Shanghai in the form of real estate investments, you would have trebled it in seven years.”

Energized by ambitious White Russians, Germans, Japanese and Jewish immigrants, Shanghai was the most ethnically diverse city in the world. The leader of the city’s business community was a Sephardic Jew named Victor Sassoon, whose family had been bankers to the Baghdad caliphs. A monocled bon vivant, Sassoon loved beautiful women and thoroughbred race horses, of which he once quipped, “There’s only one race greater than the Jews, and that’s the Derby.”

But beneath the frivolity Shanghai had become a city of intrigue. Kuomintang Nationalists were sparring with Communists for control of the city and the KMT was winning thanks to its alliance with the Green Gang, a massive criminal enterprise with 20,000 members. Nobody nicknamed Baby Face or Pretty Boy was allowed in this mob. Pockmarked Huang and Big-Eared Du ran the operation courtesy of the French Concession Consul General, who made Huang his chief of police in return for a slice of the gambling, opium and prostitution take. Observed American journalist Edgar Snow: “Racketeering flourishes with a velvety smoothness that makes Chicago gangsters seem like noisy playboys.”

In return for a monopoly of the city’s opium sales, the Green Gang routinely arranged assassinations for the KMT. The most brutal occurred in 1927 when it sent 1,500 toughs onto the streets. Their target: communist members of the Nationalist Kuomintang who posed a threat to KMT leader Chiang Kaishek. Over a three-day period, the mob killed more than 5,000 leftist writers, labor organizers and liberal academics. The massacre destroyed any hope of a united front against Japanese aggression, set the stage for eventual civil war and strengthened communist resolve to eradicate every vestige of western influence from Shanghai once it controlled China.

The old headquarters of the Green Gang lives on today as the Mansion Hotel, whose coffered lobby is an art deco memorial to the 1930s filled with period furnishings, a victrola and sepia photographs of rickshaw pullers loading cargo off sampans docked at the Bund. “The decade from1927 to 1937 was Shanghai’s first golden age,” says Fudan University professor Xiong Yuezhi, editor of the 15-volume Complete History of Shanghai. “You could do anything in Shanghai as long as you paid protection. The more you paid, the safer you were. The safest people, of course, were the gangsters since all they had to do to escape arrest was to walk across the street to a different concession”

A former French Concession mansion that once was the headquarters of the Green Gang, the mob that controlled the city in the 1920s and 1930s. the modern Mansion Hotel remembers its glory days with a lobby full of artifacts from Shanghai’s raffish past. Fudan University professor Xiong Yuezhi often stops by for inspiration, and a cup of tea. Photo by David DeVoss

Following Japan’s defeat in 1945 Shanghai awoke from its war time slumber. But as the communist noose tightened wealthy officials in the Nationalist government began quietly moving their assets to Taiwan. The clearest sign that the city’s days were numbered came in May 1949 when British journalist George Vine working late at night looked out the window of his office and saw a line of chanting men dressed in rags carrying heavy bundles out of the Bank of China on bamboo poles toward a freighter anchored at the Bund. When he realized what was happening, Vine cabled his newspaper that “all the gold in China was being carried away in the traditional manner – coolies.”

Chinese communists seemed intimidated by Shanghai’s sophistication when they finally took control of the city. Initially, they tried to promote their agrarian programs with the same symbology capitalists once used to sell consumer products. At Shanghai’s Propaganda Poster Art Center on Huashan Road it’s still possible to buy copies of a revolutionary poster from the 1950s that shows a manicured beauty with marcelled hair standing in a rice paddy smiling as if she had just smoked a Chesterfield or driven a Buick Roadmaster.

The Shanghai Revolutionary Poster Museum and store where propaganda is an art form and peasants always rule. Photo by David DeVoss

Beijing allowed capitalism to limp along for the better part of a decade, confident that socialism eventually would take root. When that didn’t happen, Shanghai was subjected to the most doctrinaire communism Beijing had to offer. When the Cultural Revolution began in the mid 1960s, the Bund’s bronze lions were gone, the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank was occupied by local Communist party authorities and Big Ching’s bells atop the old Custom House clock tower began each day by ringing “The East is Red.”

Chinese author Chen Danyan, 53, whose autobiographical novel, Nine Lives, describes her childhood experiences during the Cultural Revolution, remembers the day new textbooks were distributed in her literature class. “We were given pots full of mucilage made from rice flour and told to glue all the pages together that contained poetry,” she says. “Poetry was not considered revolutionary.”

Neither were the movies being produced by the Shanghai Film Studio, according to Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s wife and the most radical member of the Gang of Four. Before she embraced communism, Jiang was a struggling young actress in Shanghai, but during the Cultural Revolution she made sure no romances or comedies were produced. “Until Jiang Qing halted all film production, the Shanghai Film Studio was producing 60 movies a year,” says retired director Yu Benzheng, 70. “During the Cultural Revolution we were limited to eight revolutionary plays where the characters were heroic peasants, soldiers or factory workers who battled evil counter revolutionaries. Any display of creativity was punished severely.”

The Cultural Revolution had been over for three years when I first visited Shanghai in the summer of 1979. China’s new leader, Deng Xioping, had opened the country to tourism and expressions of public opinion were being posted every night on Beijing’s Democracy Wall. But when my American travel group arrived at Shanghai’s train station we were met by two scowling Red Guards who made it clear they did not like hosting a bunch of capitalist roaders. Our first destination was a locomotive welding factory and on the ride over their welcoming remarks consisted of “Don’t take that picture” and “Why do you want to know the name of that building?”

As the bus rolled along streets filled with people dressed in blue Mao suits riding Flying Pigeon bicycles, Shanghai looked as if it had gone to sleep in 1949 and just awakened. There was no new construction. Grimy art deco mansions and streamline Moderne apartments festooned with bamboo laundry poles had been divided then divided again to pack as many families in as possible.

American capitalism and Chinese communism have a symbiotic relationship when it comes to travel souvenirs. Photo by David DeVoss

I stayed at the Jinjiang Hotel, a Georgian-style structure built by Victor Sassoon in 1929 that seven years before had hosted Richard Nixon and Zhou Enlai when they signed the Shanghai Communiqué. The hotel had no city map or concierge, so I consulted a 1937 Shanghai guide book purchased earlier in the Asian History section of a Hong Kong bookstore. It recommended the Grand Marnier soufflé at the Chez Revere, a nearby French restaurant on a boulevard once called L’ avenue Joffre.

Chez Revere had changed its name to the Red House, but the elderly Maître d’ boasted it still served the best Grand Marnier soufflé in Shanghai. After I placed my order, however, there was an awkward pause followed by a look of Gallic chagrin that captured all that Shanghai had been and what it has lost. “We will prepare the soufflé,” he sighed, “but Monsieur must bring the Grand Marnier.”

A towering statue of Mao continues to guard the main gate of Fudan University, but the underground bunker he used to move between his apartment at the Cercle Sportif François and the Jinjiang Hotel across the street is used now by the Okura Hotel to store broken furniture and garden implements. The elegant French club has been beautifully repurposed as a luxury hotel, but the split level apartment where Mao slept is a utility room filled with machinery.

Statue of Mao at the entrance of Fudan University in Shanghai. Fudan and Beijing University are two of the most prestigious schools in China. Photo by David DeVoss

During the 1990s, the vast swaths of shanghai preserved intact for more than four decades were redeveloped. Over a four-year period starting in 1993, Shanghai’s municipal government leased parcels amounting to more than three square miles of land to developers indifferent to the architectural and social cohesion of the city. Hundreds of intimate Chinese neighborhoods called lilongs accessed through distinctive stone portals called shikumen were razed.

Although development continues at an unprecedented rate, more thought is given to the nature and placement of new buildings. “We have succeeded in our goal of making Shanghai the world’s leading financial center, but we know that people coming here for business still want to see our history,” says Yao Kai, Director of Urban Planning at the Shanghai Municipal Planning and Land Use Administration. “Twelve historic preservation zones help balance development with preservation.”

Many of Shanghai’s classic buildings never have been in better shape. The 1929 Peace Hotel on the Bund, where Noel Coward wrote “Private Lives” during a four-day bout with the flu, underwent a $73million renovation to restore its original Art Deco splendor. Even the Great World has reopened, albeit with less risqué entertainment.

In Shanghai, old literally has become new. The city’s hottest nightspot, Xintiandi (New Heaven and Earth) is a lilong neighborhood two blocks long that was torn down and rebuilt in its original 19th century form so that restaurants like TMSK can serve Mongolian cheese with white truffle oil to patrons as they listen to the cyberpunk stylings of electrified Chinese musicians.

Nobody arrives at Xintiandi on a Flying Pigeon. And Mao suits have as much appeal as whale-boned corsets for modern Shanghai women, most of whom appear to believe that couture is de rigueur. “Shanghai is a melting pot of different cultures, so what sells here is different from other Chinese cities,” says fashion designer Lu Kun, who numbers Paris Hilton and Victoria Beckham among his clients. “No red cheongsams or Mandarin collars here,” he admonishes. “Sexy, trendy clothes for confident, sophisticated women; that’s Shanghai Chic.”

Lu Kun is one of Shanghai’s leading fashion designers who specializes in “Shanghai Chic.” Celebrities in London and Hollywood wear his gowns to award presentations. Photo by David DeVoss

Luxuries are affordable because of high-paying jobs that result from the city’s hyper development. Unlike Los Angeles, for example, where the budget is funded by citizen taxes, Shanghai’s municipal government gets its money from the residential and commercial leasing of land that remains the property of the state. Because communist leaders built nothing for 40 years, there’s plenty of available land and a political system, called “market economy socialism,” that permits public debate on developmental issues but no opposition once the government makes its decision.

Several years ago, Shanghai began moving its heavy industry and manufacturing to the edge of the city. Now new immigrants are encouraged to settle in pre-planned communities on the city fringe. Nine new cities, each with 500,000 residents, 60 new towns with populations ranging from 50,000 to 100,000 people and 600 villages are being built to move density out of the city and into the suburbs. All new development is required to use renewable energy technologies that include solar panels and wind turbines.

“The Shanghai of 2020 is an ecologically friendly green city,” says Qiyu Tu, director of Shanghai’s Center of Urban Planning and Regional Studies. “The city can’t sustain double-digit growth if it continues to rely on fossil fuels. The logic of becoming a low carbon society is inescapable.”

“Better City, Better Life” is Shanghai’s official motto. But “Keep Moving” more accurately describes social behavior when it comes to pedestrians. Photo by David DeVoss

Shanghai also has the world’s most modern and extensive public transit system. In 2005, Shanghai had three subway lines. By 2011 it had 12. Today it has 23 commuter rail lines with more on the way since the city’s population is expected to reach 34,000,000 by 2035.

Many of the new towns at the end of the lines are themed communities. Located south of Pudong on the east side of the Huangpu River, Pujiang has an Italian theme that requires apartment courtyards to resemble Roman piazzas. German-themed Anting northwest of Shanghai features Bauhaus architecture similar to that in Weimar, Germany. Qingpu north of the city feels like a Ming Dynasty village, except the stone bridges over canals lead to houses with contemporary interiors.

The new suburban city of Songjiang in Pudong contains small towns designed for Anglophiles. Thames Town has cobbled streets, Georgian and Tudor facades, an unconsecrated Gothic chapel and mini manor houses starting at $900,000. Included in the town’s scenography are fish & chips shops and bronze statutes of Winston Churchill and Harry Potter. People with roots planted across the Pond can live in Santa Barbara Villa, a neighborhood with Southern California mission architecture.

Hua Cao in southwestern Shanghai also has a generic American feel. It has a Coldstone Creamery, Papa John’s Pizza, single family homes selling for up to $2 million and the main campus of the American School. The school’s enrollment has grown from four students in 1981 to 3,500 despite a $29,000 tuition. The demand for space is so great that corporations buy $25,000 debentures to save seats for the child of incoming executives.

Luxury homes and mansions on the outskirts of Shanghai within walking distance of the American School. Photo by David DeVoss

“Corporations often have a problem getting their executives to leave Shanghai,” confides T.K. Ostrum, the school’s admissions director. “Families decide to stay and start their own business. Some of our graduates even attend Fudan University and make Shanghai their home.”

There is no end in sight to the largest urban transformation in human history. The population of Shanghai, whose municipal motto is “Better City, Better Life,” grows by 450,000 a year. Immigration accounts for the entire amount. Nearly 1,500,000 Taiwanese work in and around the city. Shanghai’s American population exceeds 40,000. Many are Chinese Americans like Yongguo Wu, 49, whose South Carolina-based company produces electrical cables for the aerospace and defense industries at a Pudong factory working three shifts 365 days a year. “Two years ago, a team of American engineers came here to help us improve manufacturing,” Wu smiles. “After a while they realized that our quality is higher than that of the United States. Now my employees go to the U.S. as change agents to teach Shanghai best practices.”

For native-born residents like author Chen Danyan the pace of change is a bit disconcerting. “People look for peace in the place where they grew up. But I come home after three months away and everything seems different,” she sighs. “Living in Shanghai is like being in a speeding car, unable to focus on all the images streaming past. All you can do is sit back and feel the wind in your face.”![]()

David DeVoss is editor and senior correspondent of the East-West News Service.