Saigon’s City Hall was built by the French, but today it’s presided over by Ho Chi Minh, who remains the most revered of the country’s post colonial revolutionaries. Photo by John Gottberg Andreson

By John Gottberg Anderson

My first semi-permanent home in Saigon, better known to many by its official name of Ho Chi Minh City, was in a hem (a narrow urban alley) in the heart of the city’s old banking district. It was only four blocks from the Calmette Bridge over the Ben Nghé canal, a similar distance from the quaint shops of “Antique Street,” and a few staggering steps from the hostess bars of Pasteur Street — about 10 minutes’ walk southwest from the place where Dong Khoi street (known as Tu Do to American GIs) meets the Saigon River.

The neighborhood is a mix of starched suits and sodden souls, of karaoke clubs and soup kitchens, of high heels and low morals. Motorbikes block the entrances to some of the city’s finest restaurants. Off-leash family dogs slurp offerings left on sidewalks for deceased ancestors.

The front section of the hem is dominated by food carts from dawn until half past noon. Bankers, business people and other diners squeeze onto plastic stools, allowing barely enough room for a motorbike to skirt past. Noodle soup, chicken rice, fish, snails and other meals cost no more than $2.

Further back, street food transitions into retail establishments and a trio of sit-down restaurants. Office girls look dreamily through the window of a bridal shop, a small steakhouse features ostrich on its menu, an upstairs tea room is rumored to have once been an opium den. Indeed, the history of this discreet block might be considered “sketchy.”

I often find myself reminiscing on my first residence. I miss sitting in the parlor of my home on a balmy day, shouting to a merchant who might deliver bò kho (beef stew) or cơm tấm gà (chicken rice) without my ever having to change position. I miss the sounds of morning and evening, the caged songbirds and chirping geckos, the yowling of tomcats on the prowl, the impromptu karaoke singing sessions, the cadent chants of Taoist funerals when a neighbor has died.

Saigon street food is cheap, plentiful and delicious. Photo by Son Vu Le

As a veteran journalist, I had come to Vietnam from the United States in October 2019 for a multitude of reasons. My only child had died three years earlier. My brother was living in Japan. My best freelance writing markets were drying up, and I hadn’t saved wisely for retirement. I knew Southeast Asia from previous visits, including a long residence in Singapore in the 1980s. The region’s cost-of-living, relative to the States, was an attractive incentive. And at the age of 69, I was ready for a new adventure.

Vietnam offered the opportunity to supplement my income by teaching. My resume included a couple of stretches as a university journalism instructor in Washington and Oregon, but exposure to child education had eluded me. Now, after completing a one-month certification course in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL), I would join the younger set, starting with kindergartners at an independent private school.

Urban progress

Once settled in a job, I was ready to venture beyond my hem sweet hem to discover other faces of the city. Where Le Loi crosses Nguyen Hue and Dong Khoi (Tu Do), turbulent 20th-century history meets a city striving to become a relevant 21st-century metropolis.

At the Hotel Continental Saigon (once the Continental Palace), Sunday brunch at Le Bourgeois remains a special occasion, much as it was for author Graham Greene in the early 1950s when he wrote The Quiet American. Those who gather at the Continental now see a newly manicured park block fronting the elegant Saigon Opera House, a 19th-century remnant of French colonial architecture. Here, high-fashion models pose for photographs, while high-profile dance productions and symphony concerts draw the cream of local society.

Afternoons and early evenings can still get boisterous a block to the west in the Rooftop Bar of the Rex Hotel, where scores of international journalists hoisted glasses during the Vietnam (“American”) War. Imbibers now gaze down upon broad Nguyen Hue boulevard, redeveloped as a pedestrian zone in 2015. At its heart is a larger-than-life statue of city namesake Hồ Chí Minh, his right hand raised in an oath of commitment to the Vietnamese people.

Gourmands and guzzlers alike have front-row seats for the continuing construction of a six-line Metro subway system that will have its hub beneath a new pedestrian plaza opposite historic Ben Thanh market, less than a half-mile southwest of the Rex.

Over the 45 years since the end of the war much of Saigon’s old French colonial city has been redeveloped to become a modern metropolis that rivals Asia’s leading cities. Photo by Peter Nguyen

New perspective

The rest of the world struggled through 2020 with the COVID-19, but Vietnam was largely spared. As of early March 2021, the country had recorded only 2,500 cases of the coronavirus with just 35 deaths. The vigilance of the government in enforcing social distancing and the wearing of face masks, along with a relentless system of tracing the contacts of those infected, receives much of the credit.

Vietnam closed its airports to international flights early in the pandemic and they remain closed except to readmit overseas Vietnamese (Việt Khiều) and essential Asian business travelers — all of whom are subject to two weeks’ quarantine. Caution puts a crimp in tourism, which contributes mightily to the national economy. Speedy reopening depends on the success of COVID vaccines.

None of Vietnam’s eight UNESCO world heritage sites are in Saigon, but there’s still plenty to see here. Visitors may ascend to the cloud-scraping observation deck atop the Landmark 81 Tower, built in 2018 to a dizzying 1,513-ft (461 meters) above the Binh Thanh district. Those exploring downtown Saigon may prefer the 49th floor Skydeck of the Bitexco Financial Tower, two blocks off Nguyen Hue. It was here that I first understood the geography of this sprawling city.

Ho Chi Minh City stretches in all directions, flat as a bánh xèo, a rice-flour pancake. Yet even from this perch, the famously polluted air (fouled by vehicle exhausts, coal-fired factories and construction dust) doesn’t allow one to see west toward the Cambodian border hills or southeast to the South China Sea. Instead, one glimpses the broad and muddy Saigon River meandering around modern high-rises that cluster on its west bank. Here and there, smaller tributary canals divide neighborhoods. Across the main channel, new cities of residential skyscrapers in the less congested Districts 2 and 7 are popular with foreign residents.

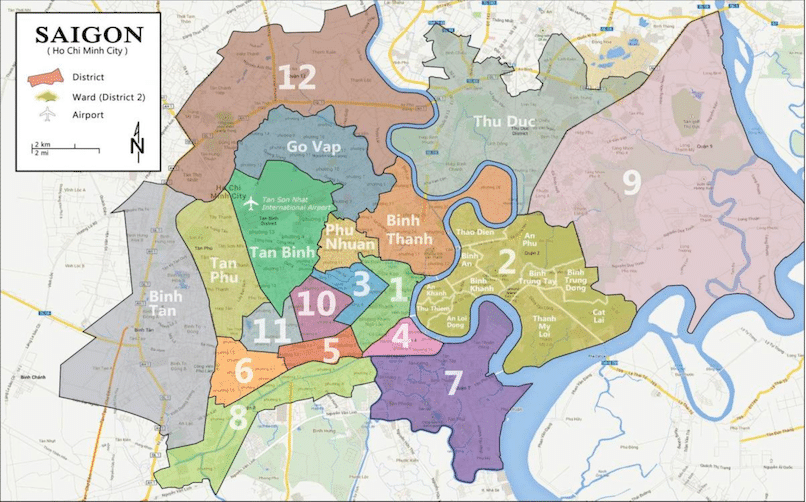

Ho Chi Minh City is divided into 12 quận, or districts. Most “tourist attractions” are in District 1, the central commercial and nightlife district. Immediately northwest is gentrified District 3, where colonial-era houses now serve as foreign consulates. Southwest, past the infamous bars and brothels of the Bui Vien walking street, is Cholon (District 5), Saigon’s historical Chinatown.

Ho Chi Minh City is divided into 12 quận, or districts. Most “tourist attractions” are in District 1, the central commercial and nightlife district. Immediately northwest is gentrified District 3, where colonial-era houses now serve as foreign consulates. Southwest, past the infamous bars and brothels of the Bui Vien walking street, is Cholon (District 5), Saigon’s historical Chinatown.

Beyond the flatlands of Saigon, the topography does change. To the south and west is the broad Mekong Delta region, its hub at Can Tho, a city of 1.5 million, famous for its floating markets. To the northeast, the Central Highlands rise to more than a mile high. Smaller, cooler cities like Da Lat, renowned for its gardens and coffee farms, offer a welcome escape from Saigon’s heat. The beaches of Mui Né and Nha Trang, 250 miles from Saigon, and other resort cities are lapped by the waves of the South China (or East) Sea. All are popular getaway spots for city residents of means.

In Vietnam, the most popular form of transportation is the motorbike. By some estimates, more than 8 million motorbikes are in use in Saigon alone. Entire families (dad, mom, three kids and a dog) can often be seen riding a single vehicle. And the quantity of goods that can be stacked upon a bike is staggering.

There are 8 million motorcycles in Saigon and all of them demand the right of way when you try to cross the street. Photo by Matthew Nolan

South and north

Vietnamese like to say they have a “small country.” It is, in fact, a medium-size country with a large population — 97 million, more even than Germany. Ho Chi Minh is the second largest city in mainland Southeast Asia (after only Bangkok), with 9 million urban residents and a metropolitan population estimated at 21 million. Hanoi, the national capital, is marginally smaller with 8 million people.

A conservative Confucian-Taoist ethic shaped by more than a millennium of Chinese influence has imbued northern society with a cultural legacy more traditional than progressive. Utmost importance is placed upon education, which is rigidly guided by communist party doctrine.

In the Mekong Delta and Central Coast, the Cham (Hindu) and Khmer empires wielded more impact than China in ancient times. The south is more open to international influence. Tradition and family values remain important, but what you know is as significant as who you know, encouraging more entrepreneurism.

In the arts, creative expression is encouraged, as long as it is not critical of the government: Artists, writers and musicians need not always play by the rules. For example, “Rap Viet” has become a popular western-influenced form of contemporary music, with its own local stars. Even the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam recorded rap lyrics in a 2021 New Year’s greeting.

English lessons

To many Vietnamese, the United States remains the “promised land.” It seems that everyone has a relative living the good life in the United States, typically in California, Texas or Florida. Việt Khiều, as the overseas Vietnamese are known, frequently visit Vietnam, especially during the Tét holiday.

English is widely (if haltingly) spoken and taught as a second language. Visitors and foreign residents have no difficulty in communicating at shops and restaurants, especially in districts 1, 2 and 3, where English is clearly the language of tourism. A smaller number of Vietnamese also speak Chinese, Korean, Japanese and/or Russian, but almost no French despite the Europeans’ former colonial presence.

The Vietnamese ao dai is both sensuous and practical. The long sleeves and light fabric guard against sunburn and excessive heat. Photo by Vaory Photography

Americans are widely liked and trusted by Vietnamese. The collision of cultures that occurred in the 1960s and ’70s lives in the past. Although American music lovers are hard-pressed to find live venues (karaoke bars definitely take precedence), it’s easy to catch recent U.S. movies, either beside Vietnamese features on cineplex screens throughout Ho Chi Minh City, or on Netflix and other satellite TV networks.

International magazines are widely available at a handful of newsstands in tourist districts. And as a foreign resident, I’ve never encountered any firewall in accessing world news on the internet.

Food and drink

Phở, the world-famous beef noodle soup, originated in the north around the start of the 20th century, while bánh mì, baguette sandwiches filled with pork and pickled vegetables, are credited to the French colonial period in the south. Enjoyed with rice or noodles, steamed or simmered or fried, ingredients are invariably fresh. Soups and salads are an integral part of the cuisine. Seafood is superb, chicken and pork excellent. Salt and spice find a balance with sour and sweet.

Chefs often start out cooking on the street but as their fame spreads they often end up operating seated restaurants.

Street food is everywhere. No one location is best, although public-market precincts have a greater concentration of options. In District 4, just across the Ben Nghé canal from District 1, Vinh Khach street is a remarkable avenue of shoulder-to-shoulder seafood eateries offering fresh fish, prawns, squid and shellfish.

As befits a city with a French colonial heritage, Saigon has many excellent French and French-influenced restaurants. At the head of the list is Quince in District 1 where chef Julien Perraudin serves a menu highlighted by tartine de cochon and moulard magret — pig’s head and fattened duck. For something more American-style, District 2’s Mekong Merchant has a long-established following for its steaks and pizzas.

Young Vietnamese professionals gather at coffee shops to socialize and text, which makes them similar to young professionals in Tokyo, Los Angeles or London. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Vietnamese love their beer. The craft brewing industry is booming, with brands like Heart of Darkness on Lý Tu Trong and Pasteur Street Brewing on Lê Thanh Tôn finding a place on many restaurant menus.

Even more prominent is coffee. National chains, including the ubiquitous Trung Nguyên and Highlands coffee shops, dominate on the main streets. Here, people of all ages, notably the young, gather for conversation and often romantic trysts.

Not into coffee after dark? Join the expat crowd to tipple at places like District 2’s Buddha Bar or watch Australian football at Phatty’s Sports Bar in District 1. Searching for companionship in District 1? Pricey “lady drinks” will guarantee you conversation in the Little Tokyo neighborhood at the east end of Lê Thanh Tôn or on Pasteur Street north of Hàm Nghi.

Sights of Saigon

Curious about the Vietnamese war? Then go to the War Remnants Museum on Võ Van Tân, in District 3 where a $16 ticket comes with an English-speaking guide. It’s hard to look at graphic photos of Agent Orange attacks, whose victims still haunt Vietnam’s streets. Captured U.S. tanks, warplanes and artillery are presented in the museum yard.

What did yoiu do in the war, Daddy? Actually, most visitors to Saigon’s War Remnants Museum are too young to have fought in the war. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

North Vietnam tanks crashed the iron gates of Independence Palace on Lê Duân, in District 1 in April 1975. Saigon’s name was changed to Ho Chi Minh City the following year when north and south become a unified Vietnam. The grand but utilitarian palace is open daily for tours in English, French and Vietnamese. It doesn’t take much imagination to envision the military intelligence operations that were coordinated in the basement bunker where rows of telephones, telex machines and short-wave radio transmitters stand just as they were in 1975.

Saigon’s ornate, yellow Central Post Office at the north end of Dong Khoi is a prominent reflection of the French colonial era. Built in the 1880s, it often is credited to the same Gustave Eiffel responsible for his eponymous tower in Paris. Directly opposite is the city’s famous Nôtre-Dame Cathedral, now swaddled in scaffolding for restoration. The neo-Romanesque basilica was built of Provençal brick by French colonists between 1863 and 1880.

Among scores of temples in Saigon, the incense-shrouded Jade Emperor Pagoda on Mai Thi Luu near Dien Bien Phu street in District 1 is a fine example of the unique amalgam of Chinese faiths. Built in 1909 to honor the Taoist king of heaven, it also nods to Confucian and animistic beliefs, and Chinese characters in the main hall may be translated to read, “The light of the Buddha shines on all.” Grotesque statuary and fine woodcarvings make it well worth a visit. Outside in a small pond, turtles whose shells bear Chinese inscriptions clamber over one another.

The Jade Emperor Pagoda in District 1 blends Taoist, Confucian and Animistic spirituality and welcomes all visitors. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Because most Vietnamese work at least six days a week, there’s not much of a weekend getaway culture. For those who do, the seaside town of Vung Tau, two hours by land or sea, is a popular destination. Some tourists make a short journey to the Cu Chi tunnels, an infamous corner of the Ho Chi Minh Trail just northwest of the urban region. Others glimpse Mekong Delta heritage on a day trip to Ben Tré and My Tho, where they may paddle canoes down a river and through a floating market.

As for myself, you just might find me on a Saigon Sunday morning enjoying a croissant and café au lait at Tous les Jours, one of the city’s finest French patisserie chains. From here, I may stroll past the cafes that line the Thi Nghé canal in the Phu Nhuan district, or salute the monkeys and elephants in the newly renovated Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens. If the spirit moves, before a dinner of bavette steak with foie gras at Quince, I may amble down Nguyen Cong Tru street and slip into the discreet hem where I made my earliest memories in this energetic city. And I’ll be tempted to pass up the steak in favor of a piping bowl of bò kho or a plate of cơm tấm gà.

If You Go

Flights: Saigon’s Tan Son Nhat International Airport is presently closed to flights from North America. Until they resume, the most direct route is via Qatar Airlines from New York, a journey that requires changing planes in Doha, Qatar, with a 15-day hotel quarantine upon arrival in Vietnam.

Where to Stay: The Park Hyatt Saigon is the city’s most elegant hotel. Many other international chains are located here, including Intercontinental, Le Meridian, Sofitel and a soon-to-open Sheraton. Historic properties like the Continental, Caravelle and Majestic offer classic sophistication.

Currency: There are about 23,000 VND (Viet Nam Dong) to $1. Bills come in 10 denominations, from 500 VND (about 2 cents) to 500,000 VND (US$21.78). Vietnam uses no coins.

Getting Around: A taxi from Tan Son Nhat airport to downtown Saigon about five miles away will cost about 200,000 VND, or $9. Motorbike taxis, which have replaced cyclos as the preferred form of urban public transportation, cost about 50,000 VND for the same distance, depending upon time of day.

Getting Around: A taxi from Tan Son Nhat airport to downtown Saigon about five miles away will cost about 200,000 VND, or $9. Motorbike taxis, which have replaced cyclos as the preferred form of urban public transportation, cost about 50,000 VND for the same distance, depending upon time of day.

When to Go: Anytime between October and April is a good time to visit. Avoid the two-week Tét holiday since cities empty and with them many restaurants and tourist services. In the rainy season, which begins in May and extends through September, frequent storms overwhelm the city’s drainage system making many thoroughfares impassable.

Language: Although English is widely spoken in the hospitality industry, it’s helpful to learn a few phrases of Vietnamese, including Xin chào (hello), Cảm ơn (thank you) and Một, hai, ba, yo! (one, two, three, cheers!).![]()

Author of 19 books, John Gottberg Anderson, has worked for The Los Angeles Times and edited Michelin and Insight Guidebooks. He resides in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) and writes a blog called TravelsinVietnam.com.