Peles Castle near the village of Sinaia 77 miles from Bucharest is considered one of Europe’s most beautiful 19th-century castles. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

By Jacqueline Swartz

Romania conjures mysterious and sinister images of Count Dracula and the Transylvanian forests. The foreboding Bran Castle high in the Carpathian Mountains certainly looks like the location of Irish writer Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Stoker’s story of vampires rising from their coffins is an invented tale. But in autumn when twilight comes early it’s easy to imagine ghostly spirits of the undead lurking in the shadows.

Romania hasn’t truly been discovered by North American tourists. The capital, Bucharest, has been described – usually by people who’ve never been there – as a city ruined by the drab buildings imposed by Communist-era dictator Nicolae Ceausescu.

Yet the Bucharest I saw was a bustling metropolis with museums and traffic jams, wide boulevards and cobblestone streets, good restaurants and late-night clubs. And a handful of lakes and gardens.

There are ugly high-rises in Bucharest, but there are also grand belle epoque mansions and art deco gems from the inter-war period, when the city was nicknamed ‘Little Paris’, when writers such as Tristan Tsara, father of surrealism, frequented the city’s many cafes. It seems fitting that the artful discord of the surrealist movement comes from here. People speak a Latin language in a country bordering Hungary. And there’s still a Latin verve, along with a droll sense of humor. It’s not surprising that Eugene Ionescu, the well-known master of the Theatre of the Absurd, comes from Romania.

Bucharest, with its Old Town cobblestone Lipscani district, is a lively European city, with plenty of nightlife. Most of the time I felt like the only North American visitor, although there were plenty of tourists from Austria, Hungary and Italy.

Grants from the European Union have restored many Old Town buildings that survived the Ceausescu years (1965-1989). Bucharest is a walkable city. A center of trade since the Middle Ages, many of the streets here are named for guilds.

There is little uniformity, and you never know what you’ll come upon. Pasajul Macca-Vilacrosse is a glass-roofed arcade, with outdoor cafes and people smoking water pipes or nargiles, a sign of the Turkish influence in this Southeast European country. On another nearby street, at Strada Sepcari 18, you’ll find Beros & van Shaik, a trendy wine shop and bar, and a good place to taste some of the vintages of this wine-producing country.

Nearby is the Old Princely Court and Church, built in the 15th century by Vlad Tepes, or Vlad the Impaler, otherwise known as Vlad Dracula.

Vlad Tepes, aka Vlad the Impaler or Vlad Dracula, surveys the ruins of Bucharest’s Old Princely Court and Church. Vlad was real but not all the tales attributed to him by Bram Stoker are. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

The former royal palace, now the National Museum of Art, is the place to see works by the famed Romanian abstract sculptor, Constantine Brancusi. Among the many churches, mostly Eastern Orthodox, the most endearing is the Biserica Stavropoleos (on the street of the same name), dating from 1724. It is covered in murals and known for its peaceful courtyard and columns built in the ornate Romanian style called Brancovencs.

One building known for its perverse appeal is the House of the Republic, Ceausescu’s gargantuan vanity project, five times larger than the Palace of Versailles. Inside this monument to megalomania are endless marble halls and chandeliered ceilings. The building now houses the Romanian Parliament and the exhibits of the Museum of Contemporary Art. Guided tours in English can be booked at the gift shop.

Fortunately, the dictator’s neglect of the Old Town and Romania’s long recovery afterward means gentrification has not ravaged the place. What’s more, prices can give the Western visitor sticker shock – in a good way. (The currency is the leu, worth approximately 4.7 to the US dollar.)

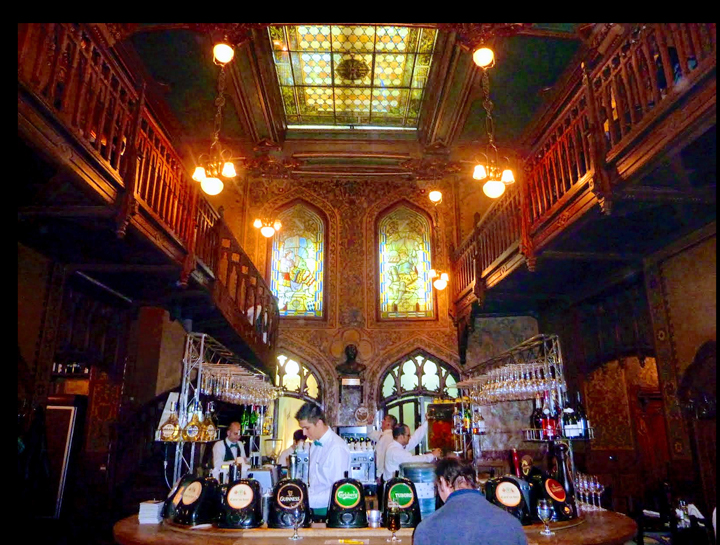

A great example of Bucharest’s weathered elegance is the must-visit restaurant, Caru’ cu bere, or beer cart, a multi-room Old Town restaurant built in 1879 in neo-Gothic style with vaulted ceilings and a large outdoor terrace. On the extensive menu, the traditional cabbage rolls with polenta, sour cream and chili pepper sauce cost about $14. A selection of dips – smoked eggplant, roasted pepper, bean casserole – runs about $7. A bottle of house wine – Romania has many wineries – is $18. The price includes entertainment: live music every afternoon at 1:30 p.m. and throughout the evening. I saw a string quartet one day and a flamenco group on another.

Bucharest’s best restaurant, Caru’ cu bere or the Beer Cart, offers Old World elegance, modest prices, an extensive menu and hours of entertainment every day. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

I found another bargain at the pharmacy across the street from the five-star The Grand Hotel Continental, which occupies a restored 1886 building. I had heard of the late anti-aging pioneer Dr. Ana Aslan and her skin care products called Gerovital, so I eagerly bought the top-of-the-line face cream – for a low drugstore price. Renovated Aslan anti-ageing clinics are open in Bucharest.

A Park Full of Village History

The Bucharest Village Museum in Herastrau Park displays three centuries of rural life through houses, churches, watermills and other examples of village architecture. As well, there are some 50,000 objects, from cooking utensils to shrines. The 35 acres are organized according to regions. Some of the 346 structures were moved, others are recreated. In many you can go inside.

Transylvania

My first stop outside Bucharest was the village of Sinaia, with its forested mountains and pure alpine air, about 77 miles from the city. I went by car, but the train stops here, and first-class travel is inexpensive and efficient. Passengers disembark to visit the neo-Renaissance Peles Castle, considered one of the most beautiful in Europe. Built at the end of the 19th century, its gardens and statues can leave you breathless, certainly after ascending the Palace’s long, steep walks. The dozens of rooms look almost lived-in; the dining room table is set for 36.

Peles stands in stark contrast to Bran, Romania’s best known castle. It belonged to Prince Vlad Dracul, even though the model for Bram Stoker’s fictional Count Dracula probably never spent a night there. Vlad, known as Vlad the Impaler, was a prince who kept the Ottoman conquerors at bay. Although Dracula is pure fiction, when I saw the castle in the drizzling rain, surrounded by the brooding Carpathian Mountains, even its red roofs looked menacing. The castle’s secret staircases and heavy wooden furniture feed the fevered imagination of Dracula fans. And there are plenty of Dracula souvenirs in the gift shop. The under-appreciated star of the castle is Queen Marie (1885-1938), the last Queen of Romania, who really did live there.

About an hour’s drive from Bran Castle is the city of Brasov, founded by German Teutonic Knights in the 13th century. Brasov is a popular spot among Romanians for its laid-back atmosphere and restored central square. The shops and restaurants surrounding the square have kept their medieval and 18th-century styles. Sergiana, a large rustic restaurant with white arches and beamed wooden ceilings, features a menu of Romanian specialties like wild boar and venison pastrami. (In Romanian the word means any spiced meat.)

The city of Sibiu, 71 miles west of Brasov, could be Brasov’s more artful twin. Its grand square has been attracting crowds ever since 1366. On the northwest corner is Brukenthal Palace, one of Romania’s best examples of Baroque architecture, with an outstanding art collection including French, Flemish, German, Dutch and Italian paintings.

Fanciful dormer windows in the historic town of Sibiu have been monitoring the municipal square since 1366. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

Also worth visiting is the Museum of Pharmacology, located in a building dating from 1569. Samuel Hahnemann invented homeopathy in the basement of the house. Some of his plans and vials are displayed. Elsewhere there are thousands of medical instruments and pharmaceutical jars.

Driving north, I was reminded that most of Romania is rural, much of it wild. The Carpathian Mountains, which cover about third of the country, are thick with fir trees, hills dotted with grazing sheep and fields of corn and haystacks. The mountains look primeval with good reason: Romania has some of the largest expanses of virgin forests in Europe. Its wolves, bears and lynx are naturally protected in this unspoiled habitat.

From the mountains, I went straight down into the Priad Salt Mine – a weird wonder. A bus takes you underground, where you descend what seems like hundreds of stairs before coming upon an enormous open expanse of salt. The floors look and feel like marble and the walls glitter. You never know what you’re going to find: sculptures hewn from salt, a restaurant, a chapel, a gym. The negative ions of salt are supposed to be good for respiratory problems, and sure enough, breathing seemed easier.

In the nearby mountains of Sovata, spas and resorts surround picturesque Ursu (Bear) Lake, known as the Dead Sea of Transylvania due to its high saline content. The sprawling four-star Danubius Hotel uses heliothermal waters and mud from the nearby lake for its pools, mud wraps and facials. (Romania has a third of the thermal waters of Europe, and spas are an old tradition). The Danubius spa is professional, glamorous and inexpensive. The woman at the front desk spoke perfect English – not always the case when you travel far from the capital. Indeed, Hungarian seemed to be the second language, and for good reason: Transylvania used to be part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and some of the residents and many of the tourists are Hungarian.

Outside Bucharest on the dirt roads of the Carpathian Mountains cars yield to horses. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

Only seven miles away, the landscape was farmland flat. At the end of a dirt road, I ended up at Casa cu Flori, a charming inn with friendly owners and hearty, homemade food. Like everywhere else I traveled, the WiFi was impeccable, which seemed incongruous given the scratching chickens and trout pond just beside the inn.

Nearby is the village of Miclosoara, where Count Tibor Kalnoky has carefully restored and preserved his family’s estate following 50 years of exile. The buildings have been turned into guesthouses; Britain’s King Charles owns property in the area and his guesthouse, managed by Kalnoky, is available to rent.

Charles has a connection to Vlad the Impaler – he is the 16th great-grandson of Vlad through Mary, the wife of George V. “You might say I have a stake in the matter,” he once quipped. In fact, he visits every year. In 2015 he established The Prince’s Trust of Romania, dedicated to the preservation of nature and local crafts.

At the guesthouse, visitors dine at communal tables, with the farm providing the produce. The Countess takes guests riding with horses from her own stables and guides lead hikes up the mountains. Be prepared to relax in this rural location. You won’t find TV but you will find a back-to-the-land simplicity combined with Old World charm that will tempt you to stay a few extra days.

Food and Wine

From Hungary to Turkey and Germany to Bulgaria, Romanian food is influenced by neighbors and conquerors from north to south. Menus typically include Greek salads, eggplant dip and grape or cabbage leaves stuffed with beef or pork and sauerkraut.

Romanians are serious about soup, which ranges from cream to chicken, vegetable to meat and bean.

Average per capita income of $14,000 goes a long way in Romania, which joined the European Union in 2007 and today enjoys all the perks (or plagues) of a modern wired society. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

Mamaliga, similar to polenta, is another staple, often served with melted cheese.

Beef and pork, from steaks to sausages, are plentiful on Romanian menus, along with such fish as sea bream, trout and even sturgeon.

For vegetarians, there are salads, bean dishes and fricassees of mushrooms or leek.

Desserts are not prominently featured in restaurants, although there are Hungarian-style fruit-filled crepes and baked apples.

Romania has a wine-making tradition reaching back 4,000 years and produces its own varieties in addition to better-known wines such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscat Ottonel. Rhem Azuga Cellars has been making fine sparkling wine since 1892 and is the official supplier to the Royal Family. Located between Brasov and Sinaia, the winery features a fine restaurant along with a 16-room guesthouse.![]()

Jacqueline Swartz’s last story for East-West News looked at her hometown, San Francisco.