The World’s Largest Cuckoo Clock is the main roadside attraction in Sugarcreek, Ohio. Every half hour, a gigantic cuckoo bird whistles the hour, a five-piece mechanical polka band appears, and a pair of robotic dancers in traditional Swiss costumes dance to the music. Photo by R.A. Killmer

By Mark Orwoll

Traveling every summer from New York to the Jersey Shore, my family and I often stop at one of the many service areas on the Garden State Parkway. They are…functional.

Take the Connie Chung Service Area, southbound only, at mile marker 153. Non-East Coasters might think that’s a line from The Onion or the old National Lampoon, but no. The celebrated newswoman Chung is a longtime resident of Middletown, New Jersey. Additional rest stops on the highway are named for Frank Sinatra, Jon Bon Jovi, Celia Cruz, and other inductees into the state’s Hall of Fame.

The Connie Chung rest stop doesn’t otherwise stand out. There you can fill up at the Sunoco station, grab a bite at Chick-Fil-A or Burger King, and use the perpetually busy restrooms, which almost always have an oversized floor fan running at top speed to evaporate the frequent, er, spills. And there’s usually a guy selling cheap sunglasses from a card table near the entrance.

All the service areas on the route are nearly identical, and I often confuse them. The Whitney Houston has a Popeye’s. The James Gandolfini has an Auntie Anne’s. You can grab a Starbucks Venti Caramel Ribbon Crunch Crème Frappuccino Blended Beverage at the Judy Blume.

Then I think: My god, is this truly how the road trip has devolved? Thank goodness all those service plazas on the Garden State Parkway have names; otherwise, how would you know the difference? They are, in a word, unmemorable.

It didn’t used to be that way.

The Glory Days of the Driving Vacation

The Great American Road Trip: Mom and Dad in front, 2.5 kids in the backseat of a gas-guzzling, 300-horsepower, V8 sedan; suitcases in the trunk, picnic basket with sandwiches and snacks crammed up against Mom’s legs in the front seat. The smoke from Dad’s Lucky Strikes meant cracking the windows, no matter the weather. Comic books and coloring books kept Junior and Sis occupied. Destination: the lake house, the beach resort, Aunt Edna’s 80th birthday party. Time of year: summer, of course.

Well, maybe that was true 50 or 60 years ago. The cultural dynamics have shifted since then. Smaller cars, bigger highways. Self-serve pumps instead of bow-tied gas jockeys. Comic books are out; iPhone video games are in. Dads don’t smoke anymore. But the Great American Road Trip is still a highlight of America’s seasonal calendar.

More than 200 million Americans took a driving vacation in summer 2022, according to a survey conducted by The Vacationer. Forty percent planned to drive 500 miles or more. These numbers can’t go anywhere but up.

Road-trippers are a hardy bunch. They don’t demand or expect a lot, but a few non-negotiables have remained unchanged since the Great Depression. You need a place to gas up, you need a place to have a decent meal. And you need souvenirs: rubber alligators, refrigerator magnets, Mexican jumping beans, state decals for the minivan window, and shot glasses with a decorative decal that says, “Johnson City!” Where could you find all that under a single roof?

Stuckey’s.

During the middle of the 20th Century, Stuckey’s maintained a roadside empire of 368 rest stops across 40 states.

A Granddaughter Remembers

At least, Stuckey’s used to offer all that, but things have changed.

Stuckey’s once had 368 stores across 40 states (mostly in in the South, Southwest, and Midwest). Now it has only 65 locations, many of them licensed “express” outlets tucked sadly into an underlit corner of a much larger “travel plaza,” a Stuckey’s in name only, a store within a store, punching above its weight against adjacent KFCs and Sbarros.

The chain began humbly in 1937. W.S. “Sylvester” Stuckey Sr., a struggling Georgia pecan farmer, went from selling nuts at a roadside shack to owning (or guiding) one of the country’s greatest restaurant empires through the 1960s and ’70s. They called him Bigdaddy. He led the business with a passion, signing off on every detail, including the building design.

“You knew a Stuckey’s restaurant if you saw the exterior,” says Stephanie Stuckey, Bigdaddy’s granddaughter and the company’s current chair, in a recent phone interview. “The telltale sloped roof in teal blue paint, the logo on the sign, the mid-century modern architecture that was so beautiful. The carports had the zigzag design. It was fabulous architecture. You would walk into the stores and the ceilings were sloped, with chandeliers hanging down. Beautiful craftsmanship. It looked like a cathedral. It was like the Church of Roadside Religion.”

Then the business collapsed—or nearly so. In 1964, Stucky’s merged with Pet, Inc., maker of Pet Evaporated Milk, to get the capital for further expansion. Pet took control in 1966 but left Bigdaddy as the CEO of the Stuckey’s division. Pet itself was acquired in 1979 in a hostile takeover by Illinois Central Industries, effectively leaving the Stuckey family in the cold.

The corporate owners had none of Bigdaddy’s vision. The family attitude, the smiling service, the quality of the food, the personal dedication of the directors, the super-clean bathrooms, and the souvenir smoking monkeys in red fez hats—all suffered under their corporate masters. In 1984, after closing hundreds of locations, Illinois Central Industries sold the chain to the founder’s son, W.S. “Billy” Stuckey Jr.

Granddaughter Stephanie Stuckey on the road. Photo by Duderino66/Wikimedia Commons

Third-generation Stephanie Stuckey bought the company outright in 2019 from her father and his partners, even though it was “a dumpster fire of a business,” she recalls. But the 53-year-old Stephanie was no Bigdaddy. She was simply the last surviving grandchild who had an interest.

“I hadn’t even run a lemonade stand,” she recalls in her new book, Unstuck: Rebirth of an American Icon (Matt Holt Books, 2024; 240 pages; $28). “Or anything other than grassroots political campaigns, PTA meetings, and environmental rallies. Nothing like a business.”

Stephanie’s memoir of those years as a budding CEO and later chairwoman makes for compelling reading. She tells the tale with zest, humor, and humility. The elements are dramatic: a once-great business in tatters and an unlikely female chief executive—with zero corporate experience.

The company’s assets didn’t extend much beyond nostalgia and a beloved brand name. Would they be enough to rescue Stuckey’s?

Memories vs. Reality: Always Stick with the Memories

Memories run deep through the generations. When you mention Stuckey’s, Andy Beth Miller immediately recalls her grandfather.

“My grandad was a North Carolina long-haul trucker who traveled all up and down Route 66,” recalls the writer and editor. “We have a special place in our hearts for Stuckey’s truck stops. He and his trucker buddies were families on the road. Those stops had showers and the same waitresses across the South, complete with the comfort of a slice of pie, hot coffee, and everyone knowing your name. They would coordinate using code names over their CB radios and meet up for a meal. My grandpa’s favorite [was] the famed Stuckey´s pecan log roll.

You can still buy a Pecan Log Roll at the Stuckey’s on Interstate 10 just outside Anahuac, Texas. The meals are reasonably priced, as are the kitschy souvenirs. Photo by Valentino Mauricio/The Enterprise

Patti McCracken, an author from Massachusetts, is another Stuckey’s fan. As a child in Virginia Beach, Virginia, her family would travel to see cousins and grandparents in Richmond. Even though it was just a two-hour drive, a stop at Stuckey’s was mandatory.

“We had a station wagon, the kind where the last seat faced the back,” she remembers. “We didn’t travel too far—six kids—but Stuckey’s was a must-stop. We’d stop for the pecan roll. I can still taste it, and honestly can’t imagine how we could eat something so sweet! One thing I remember is that my Mom bought my sister and me some cornhusk dolls. Small dolls, about the size of my adult hand. One for each of us. We prized those little dolls.”

Stephanie Stuckey bemoans the sameness of today’s travel plazas, where you’re unlikely to find cornhusk dolls or anything else that provides a local atmosphere.

“When you went into a Stuckey’s,” she says, “you got a sense of where you were. If you pulled into a Stuckey’s in Virginia, you would see Virginia hams or Virginia peanuts. And if you pulled over at a Stuckey’s in Texas, you would see cowboy hats. In Florida, there’d be alligators and coconut-shell sculptures and seashell wind chimes. So, you had that sense of place.”

Not the Only Game in Town

Stuckey’s gets its fair share of the nostalgic roadside limelight, but depending on where and when you grew up, there was a lot of culinary competition on the American highway.

I recently used social media to ask my friends and colleagues for their childhood road trip memories. One of them was Drew Kerr, a crisis-prevention expert for CEOs, based in New York. My question led to a flood of memories.

“When I was growing up,” he wrote, “my parents often took our family on our vacations to a place called Deer Park Lodge in Cuddebackville, New York, near Port Jervis. The mandatory road stop for us was a place called Red Apple Rest on Route 17. We would color in the menus—that was a big thing—and I was keen on the macaroni and cheese.”

It was more than the food. It was the car (the Kerrs were an Oldsmobile family), the music, the entire vibe.

“Definitely an Oldsmobile,” he continued. “Those cars were as big as boats! That’s what my father drove. He’d put on WNEW-AM on the radio, which played Sinatra, Martin, Bennett, and all those popular singers of the era.”

The Tale of Howard Johnson’s

Many East Coast drivers remember their preferred road stop being Howard Johnson’s, affectionately known as HoJo’s. Howard Johnson’s, which began with a single location in Massachusetts in 1925, was at one time America’s largest restaurant chain, and pre-dated Stuckey’s by 12 years. Its success was predicated on being family-friendly.

HoJo’s founder, Howard Deering Johnson, knew that women decided where a family would stop for a meal. He designed his restaurants to be attractive and noticeable, thanks to their bright orange roofs. The bathrooms were spotless. He perfected children’s menus, with all selections featuring chocolate milk and ice cream (select from 28 flavors!) and named for nursery rhyme characters. The Tommy Tucker plate featured sliced roast turkey. Jack Horner came with a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Little Boy Blue was a hamburger patty.

The main dish that hit a chord with most young travelers, though, was HoJo’s Small Fry, which consisted of fried clams, whipped potatoes, and a buttered roll. It cost a bit more than the PB&J, but what parent could say no to a hungry child on a road trip? Even HoJo’s logo was kid-friendly: a neon-lit “pieman” bending down to offer a stack of fresh-baked pies to Simple Simon and his drooling dog.

Postcard of Howard Johnson’s in Bedford, PA. The bright orange roof meant good food and clean bathrooms.

The kids loved Howard Johnson’s and shouted energetically to stop the car. Mom insisted on HoJo’s because the bathrooms were clean. In the decision-making department, Dad may have been outgunned, but he didn’t mind. The fried clams were on the grown-up menu too.

Michael Giuseffi, a credit manager from New Jersey, remembers HoJo’s stops on his family trips. “While driving to the Catskills via the New York State Thruway,” he recalls, “it was always Howard Johnson’s and fried clams.”

HoJo’s clams also were paramount for Michael Cain, a traditional Celtic musician originally from Delaware. But summer vacation stops at roadside restaurants on the way to Cape Cod didn’t happen often. His parents instead packed ham-and-Swiss sandwiches with Wise potato chips and insulated jugs of iced tea and Kool-Aid.

“I can count on one hand the number of times we stopped at a restaurant,” says Cain, a half-century later. “From those rare occasions, maybe two or three times, my memory is of fried clams at Howard Johnson’s en route to Cape Cod.”

The West Coast Had Nothing to Compare

I grew up in Los Angeles in the 1960s. Our family car was a 10-year-old 1953 Chevy Bel-Air that often missed second gear because of a failing clutch. My parents bought it second-hand from my uncle, a high-school woodshop teacher who had installed a plywood platform that covered the entire backseat. Whenever the car turned left, my sister and brothers and I would slide abruptly to the right, slamming against the side door and each other. When it turned left…well, you get the drift. No seatbelts back then.

Like the Cain family in Delaware, the cost of road trips and the desire to “make good time” on the highways meant the Orwolls didn’t stop for meals on those few occasions when we traveled to Tijuana on a day trip to Mexico. Besides, the chain restaurants in Southern California paled compared to the might, the grandeur, and the gleaming urinals of HoJo’s and Stuckey’s.

Denny’s reputation was built on being open 24/7. Some outlets even lost the front door keys because they never used them. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Denny’s, a West Coast chain of “coffee shops,” were glorified diners. But they were magical to medical editor Christine Soares, whose family vacationed frequently in California destinations like Yosemite, San Diego, or Disneyland.

“Denny’s was the constant along all the routes,” she remembers. “I’ll never forget discovering this mysterious thing they called the ‘French dip with au jus’ sandwich. Nothing French about it, but it was tasty.”

Then there was IHOP, the erstwhile International House of Pancakes, founded in Toluca Lake, California, in 1958. With their bright blue roofs over an A-frame building, they were easy to spot throughout the Southland. But if you weren’t in the mood for pancakes or a burger, road-trip dining choices on the West Coast were abysmal.

International House of Pancakes was instantly recognizable by its bright blue roofs. Today it simply is called IHOP. Photo by Corey Coyle/ Wikimedia Commons copy.jpg

Destination Road Stops, Midway Between Here and There

There was another genre of highway stops that didn’t involve chains. They were one-off restaurants between home and your regular vacation spot that were clean, efficient and affordable. The most famous of these is Wall Drug, in the virtually nonexistent town (population 695) of Wall, South Dakota. The 76,000-square-foot touristic wonderland is in the exact middle of nowhere, precisely between your starting point and everywhere else. Wall Drug made a name for itself in 1931, before car air-conditioning, by offering free ice water to weary, overheated travelers crossing the treeless, torrid badlands of the Mount Rushmore State. After the refreshing ice water, travelers could order the tuna and noodles or roast beef platter at the 530-seat Western Art Gallery Restaurant, kill time at the Pharmacy Museum, buy a pair of pointy-toed boots or some cowboy oil paintings, pray for no speeding tickets at the Travelers Chapel, and pick up a box of “homemade” donuts and pie before continuing their onward trek, all without leaving the complex.

Just off I-95 in Dillon, South Carolina, South of the Border looms like a Brobdingnagian carnival of lights, sounds and bright signs. Its mustachioed mascot Pedro, a Mexican peasant with serape, sandals, and a sombrero, may not appeal to Hispanics, but he’s a welcome sight to millions of north-south travelers on the interstate.

“America’s Favorite Highway Oasis,” as South of the Border bills itself, got its start in 1949 as a simple beer stand, strategically positioned almost exactly 600 miles from Times Square and 600 miles from Palm Beach, Fla. Who didn’t need a beer after driving 600 miles in an unairconditioned car?

Located in Dillon, South Carolina, halfway between New York and Florida, South of the Border is a massive commercial development that lures families traveling along I-95. After filling your car’s gas tank, head to Polanco’s Bar for beer and tacos before climbing the Sombrero Observation Tower to enjoy the view. Photo by John Margolies

Today, South of the Border features Polanco’s Bar, the Peddler Steak House, two Sunoco gas stations, a convention center that can hold up to 700 delegates, and Porky’s Truck Stop for long-haulers needing supplies. More recently you’ll find Fort Pedro Fireworks, Pedro’s Pura Vida selling beach apparel and motocross gear, the 200-foot-tall Sombrero Observation Tower, Pedroland Park, the Reptile Lagoon, and rides for little kids.

You don’t need directions to South of the Border. “If you’re traveling down I-95,” says the website, “it’s kind of hard to miss us.”

Is There a Future for the Roadside Chain?

Howard Johnson’s, once America’s largest restaurant chain, with 1,000 outlets, now has none. The last HoJo’s eatery, in the resort town of Lake George, New York, closed in 2022.

On the other hand, the soulless, bleak, franchised chow houses are doing quite well.

The pancake eatery IHOP (owned by Dine Brands Global, which also counts Applebee’s and Fuzzy’s Taco Shops in its portfolio) is at its peak, with more than 1,000 restaurants around the world.

Denny’s, which began life as Danny’s Donuts in Lakewood, California, and is now run by a worldwide restaurant group, is also at a peak, with more than 1,500 international outlets.

On America’s interstate highways there are fewer memorable roadside attractions. Yes, there are more places than ever to buy gasoline, but those transit plazas are operated by state transportation departments who lease fast food concessions to unimaginative, formulaic vendors like Dunkin’ Donuts, Taco Bell, McDonald’s, Starbucks, Cinnabon and Burger King. It’s difficult to imagine that a 10-year-old today will look back longingly on a Styrofoam box of Popeye’s chicken tenders ordered on a touch-screen menu.

Most of the time California’s Cabazon Dinosaurs look like, well, regular dinosaurs from the Jurassic Period. But in the autumn of 2020 merchants decided to decorate the dinos in Christmas-themed paint. Photo by Dick Lyon/Wikimedia Commons

Fanning the Flames of Better Days

The Golden Age of road trips, though, isn’t necessarily doomed to bland corporatized uniformity, as anyone can tell you who has driven on I-10 between L.A. and the campgrounds of the Colorado River. Hot and dusty Cabazon, just off the freeway, makes Wall, South Dakota, look like a mighty metropolis, but at the edge of town sits one of the great roadside attractions of all time: the Cabazon Dinosaurs, prominently featured in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure. For my money, though, you’d be better off heading farther east to Shields Date Garden in Indio for one of the Coachella Valley’s famous date shakes, a simple meal at its patio café, and an audio walking tour through its Bible-themed gardens. Shields has been luring road-trippers to this palm grove attraction since 1924.

Sugarcreek, Ohio, isn’t just a roadside attraction; it’s a destination. “Little Switzerland,” the town’s motto, has plenty of restaurants, service stations, and affordable hotels, plus the World’s Largest Cuckoo Clock, at 23 feet high and 24 feet wide. Every half hour, a gigantic cuckoo bird whistles the hour, a five-piece mechanical polka band appears, and a pair of robotic dancers in traditional Swiss costumes dances to the music. The only problem is if you’re traveling with children: They’ll make you stick around for an extra 30 minutes to see the next performance.

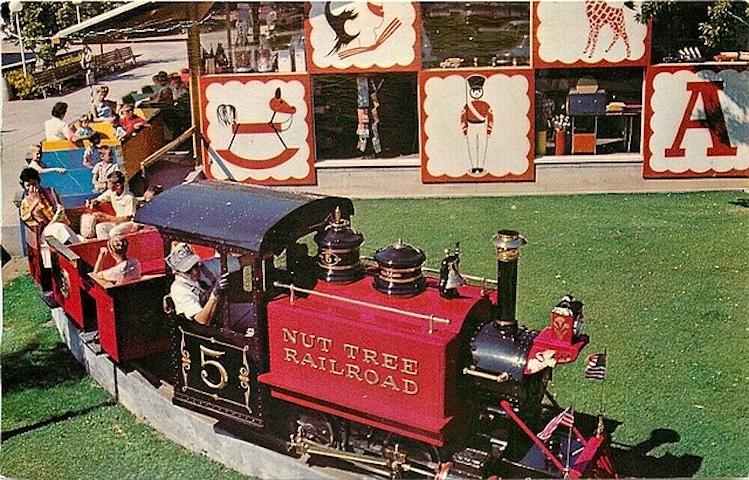

And Vacaville, California, midway between Oakland and Sacramento off I-80, is a travel plaza that all travel plazas should use as a model: Nut Tree, “California’s Legendary Road Stop,” which traces its roots to 1921. Your basic roadside needs are all accommodated: food (Japanese, Hawaiian, Brazilian, and more), souvenirs, and supplies for the road, plus a merry-go-round and a miniature train for the little ones. Travel plazas don’t have to be boring. It’s not a requirement.

Nut Tree Railroad and Toy Shop outside Vacaville, CA on Highway 80. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In the spirit of roadside dinosaurs, hundred-year-old date-shake cafés, and oversized cuckoo clocks, Stephanie Stuckey has vowed to revivify her family’s brand, which at the moment is more of a candy, nut, and snack manufacturer than a dining empire. Of the more than 300 Stuckey’s former roadside rest stops, only 15 still operate as standalone restaurants under the Stuckey’s name.

“It’s a slog bringing back a brand or starting a brand,” Stephanie Stuckey tells me. “I say we’re an 87-year-old start-up. We’re trending in the right direction, but we’re not there yet. We’re climbing the mountain.”

Until then, maybe it’s time that America went back to what the Cains did on their summer trips to Cape Cod. Sure, stop at a Stuckey’s if you manage to find one, even if they’re no longer “the Church of Roadside Religion.” But before you leave home, wrap up a half-dozen ham-and-Swiss sandwiches in aluminum foil, grab a family-size bag of potato chips, and fill up a couple of travel jugs with iced tea and Kool-Aid.

It’s time to hit the road!![]()

Mark Orwoll is a frequent contributor to East-West News Service and the former International Editor of Travel + Leisure. His most recent book is a thriller, Cross Purposes.