The Dead Sea lies between Jordan and israel at 1,425-ft. below sea level. Because of the absence of rain, nearly all of the sea’s water flows South in the Jordan River from the Sea of Galilee. Bathers can float for hours on the sea because of its salinity, which kills all fish and waterfowl.

I am floating like a cork on the salty Dead Sea, 1,400 feet below sea level, thinking about mud and history.

Earlier, at the spa in the Hotel Dan, I was slathered in the mineral-rich ooze, said to be a remedy for arthritis, skin ailments and even wrinkles. Not the usual pampering of a spa but rather a return to something primeval.

Now, in the hazy distance across the pale blue/green sea, I see the shores of Jordan; above is the mysterious stony desert, where history suggests the wicked city of Sodom was located. Indeed, were the day clearer and I had some powerful binoculars I might be able to see the weathered tufa pillar some Jordanians believe to be remains of Lot’s wife.

But my destination for the day are the caves of Qumran nearby. Here the Dead Sea Scrolls lay curled in jars for 2,000 years, preserved by the dry desert air I breathe today.

Qumran

Could this place have looked much different two millennia ago? Around the hilltop caves there is no Dead Sea souvenir shop, no falafel stand. There is an archeological site with a visitor’s centre. where a pottery making compound was found dating back to 1200 BC. But, according to a ten-year Israeli excavation, the authors of the scrolls were not the inhabitants of this site but refugees who hid the documents haphazardly in various caves as they were fleeing the Romans.

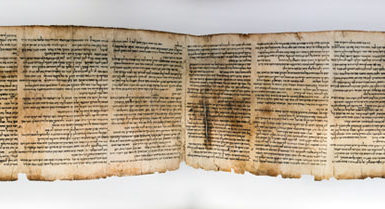

Qumran is hot, dry and mountainous. Yet in 1947 a young Bedouin shepherd looking for a lost goat tossed a pebble into a cave and heard it plunk against a vase. The 900 papyrus documents (a few are etched on copper) document the foundations of the Hebrew Bible and include the first accounting of the Ten Commandments

As for the caves themselves, with their aperture-like slits, getting to them in this rocky landscape seems daunting. It took a young Bedouin, who while looking for a lost goat in l947 idly threw a stone into a cave and heard it hit a vase, to open the way to what has been called the most important archaeological discovery of the twentieth century.

The scrolls are the earliest version of the Hebrew Bible ever found. Written on Papyrus and parchment and even on copper, these 900 documents, many pieced together from scraps, date from the third century BC to the first century AD, which makes them over a thousand years older than any previously known copies of the Hebrew Bible. There are also non-biblical scrolls – commentaries, mention of angels and descriptions of daily rituals. The War Scroll and others predict a good versus evil struggle that sounds a lot like the beliefs of today’s End of Days Christian fundamentalists.

Why did these powerful, often mystical themes of the apocalypse and the messiah come forward? The answer is still not clear, and the scrolls are still being studied.

The desert, of course, is where the three monotheistic religions were born. I explore this sun-baked terrain in a rattling jeep to the top of the monochromatic landscape. Standing on top of a tan-colored hill, long-haired Gil Shkedi, who runs Desert Tours (www.shkedig.com) points out a glittering substance veined in some of the rocks. Salt, he says, one of the most valuable commodities of ancient times, and the Dead Sea was a trade route.

Masada

Looking down from the high hills, it’s easy to imagine this area as a hideaway and a fortress. It’s not far from the most famous fortress in Israel, Masada, where Jewish Zealots resisted the Romans from 66 to 73 AD, choosing to kill each other rather than surrender.

The area was first excavated in l963, and the work has continued. Today, instead of walking up the snake path, as it is called, visitors can take a cable car. Many of the rooms in what was originally a Roman site, complete with palaces and baths, have been uncovered and offer tantalizing hints of their past. For those who want things visualized, there is the museum at the entrance, opened in 2007, complete with dioramas and dark sculptures of Romans and Jews engaged in daily life.

“I don’t go to the museum, and neither do my colleagues,” remarked Dan Bahat, one of the archaeologists on that first dig, and an associate professor during the winter session at the University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s Faculty of Theology and Christianity. He worked with legendary archeologist, Yigael Yadin, whose name is associated with Masada and who also purchased some of the Dead Sea Scrolls through an intermediary.

There are strong links between Masada and Qumran, noted Bahat, explaining that there were fragments of scrolls at Masada, and that lids were found that matched the jars that held the scrolls – not surprising, since communities along the west coast of the Dead Sea were connected through a Dead Sea trade route.

Salt caravans passed by the Dead Sea in ancient times making the arid region perfect for archaeological digs. Adventurous volunteers are welcome on some of the digs.

Who exactly were the people who wrote the scrolls? The consensus among scholars is that they belonged to a breakaway ascetic sect called the Essenes. That was until 2009, when Hebrew University Professor Rachel Elior published a book, Memory an Oblivion: The Mystery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, translated into English in 2014. In it she wrote that the scrolls were most certainly written by another group called the Zadoks. For one thing, she said, the Essenes are not mentioned in any of the scrolls, but the Zadoks are, repeatedly.

For non-scholars this doesn’t change much – the scrolls are still authentic documents. But in the competitive, scandal-ridden world of scroll scholarship, Elior’s theories are a big deal. “It shocked the scientific world”, said Bahat, who formerly taught at Israel’s Bar Ilan University.

Elior believes the scrolls originated in the library of the Second Temple of Jerusalem and were removed by the priests who fled the Temple during the conquest of the Seleucid King Antiochus IV in the second century BCE. Indeed, they could have walked from Jerusalem to Qumran in less than a day. But their retreat didn’t end there. They were rejected by the priestly group known as the Pharisees, and their sacred library went into oblivion until the scrolls were found in 1947.

Jerusalem

The Old City of Jerusalem is the natural starting place of the trail of the Dead Sea scrolls. Conquered by everyone from the Babylonians to the Romans, the Muslims to the Crusaders, Jerusalem’s Old City remains a hilly, multi-level profusion of monuments to the three monotheistic religions; it is all the more awe-inspiring for being real, not a sanitized archeological theme park. On the highest level is the Al Aqsa Mosque and the gleaming gold Dome of the Rock, which dominates the landscape. For Muslims, this is the place where Mohammed ascended to heaven. For Jews, this is the place where the two Temples once stood.

Three religions lay partial claim to the old city of Jesusalem where within the ancient walls Jesus was crucified and buried, Mohammad ascended into Heaven and the Jewish Temple once stood.

Below is the Western Wall. Alongside it are tunnels opened by archeologist Bahat, who started working on the project since l982 and was former district archaeologist for Jerusalem. On this journey through what were originally streets, there are finely carved stone walls and columns dating from the rule of Herod, once King of Judea. An aqueduct dates to the 2nd century, BC, and Arab Mamluk arches from l4th century AD.

.

The tunnels exit at the Via Dolorosa, near the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, believed to be the place where Jesus was buried. Each religion is etched in these honey-hued stones, the city’s universal color. If they could speak, they might say that Jerusalem belongs to the ages, to those who revere it, to no one group. I recalled something archaeologist. Bahat had said: “Jerusalem is a golden triangle – remove one religion and it’s no longer Jerusalem.”

Called the most important archaeological discovery of the 20th Century, the Dead Sea Scrolls are on permanent display at the Shrine of the Book in West Jerusalem. Only a portion of them are visible at any one time. The remainder travel to other museums as temporary exhibits.

It was a lot to take in, so I passed by the stalls selling Menorahs and reproductions of Byzantine icons and walked downhill to the 21st century, and the bustling shopping area of Ben Yehuda Street, on a search for silver earrings. Around the corner, at l9 King George Street, I came upon Falafel Moaz, a Middle Eastern fast food shop with comfortable outdoor seating. There I ordered a pita stuffed with fresh falafel and an assortment of toppings – eggplant, pickled carrots, tomatoes – and variety of hot sauces. A high quality version of Jerusalem’s universal food.

At the end of my journey I visited the Scrolls themselves. They’re housed on a rotating basis in their own circular space, called the Shrine of the Book, adjacent to the Israel Museum in West Jerusalem. The low, dimly lit structure is topped by a dome that is supposed to resemble the top of a jar but looks a lot like a flying saucer. The futuristic touch is a good fit with the treasures under glass, which come from the ancient past but have yet to yield all their secrets.![]()

.

IF YOU GO

For more information, contact the Israel Government Tourist Office

Where to Stay

Hotel Daniel, Dead Sea. This 4-star hotel is across the street from the Dead Sea and has a spacious spa with mud treatments, a Turkish Steam room and several different pools, one with Dead Sea water, the other with a jacuzzi.

Shkedis Camp Lodge and Desert Tours. Jeep tours in and around the Dead Sea and the Negev by day, and tents with mattresses, cushions, and a fireplace for chilly winter nights. Washrooms and hot showers are located outside the tents.

The David Citadel Hotel. Jerusalem’s most opulent hotel, designed by architect Moshe Safdie, overlooks the ancient walls of the Old City and is a few minutes walk from Jaffa Gate. Don’t miss the extravagant buffet breakfasts: eggs, cheeses, smoked fish, a cornucopia of fresh salads, breads and pastries. King David Street #7, Jerusalem. 972-2-621 1111.

Where to eat

American Colony Hotel Cellar Bar. This former Pashas palace is a boutique hotel with an East- meets-West feel; the famous bar draws the desperados of the foreign press.

1 Louis Vincent Street, Jerusalem. 1-800-7458883.

The Olive and Fish Restaurant. The decor is low key elegant, and the menu emphasizes fresh fish and vegetables. Start with the small plates of artichoke salad, sweet potato and chili, fried cauliflower, white beans, and eggplant with tahini. Aside from fish, there is chicken and meat. The wine list is impressive. 2, Jabotinski Street, 02-5665020.

Falafel Moaz. Not all falafel in Israel is good, but this take-out place with a few tables outdoors is outstanding. The falafel balls are fresh, and so are the free add-ons: pickled carrots and beets, peppers, eggplant, onions, tomatoes; red and green sauces come in various strengths. To wash it down, buy a fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice from the juice bar around the corner on Ben-Yehuda Street. l9 King George Street, Jerusalem. 02-6257706