Edgar Allen Poe

By Rich Grant

There’s a small brick basement in Philadelphia that is to mystery and horror fiction what the basement clubs of Liverpool are to rock n’ roll and the Beatles.

Thousands come every year to pay homage to the fictional stories scratched out here in the 1840s with a quill pen. Arthur Conan Doyle admitted there would never have been a Sherlock Holmes without these stories. Stephen King and Alfred Hitchcock say their inspiration for the macabre came from their love of these tales.

Today, this simple brick dwelling is so important to America’s literary history that it is maintained by the National Park Service.

But it is very different from other national historic sites. The stories that originated here portray drunken insanity, deprivation, axe murders, dismemberment, premature burial. And perhaps most terrorizing of all, a plague that swept the planet and killed everything it encountered.

This is, of course, the house of Edgar Allan Poe.

Today, Edgar Allan Poe is more familiar to the public for being Edgar Alan Poe than he is for his actual writing. People may know titles such as The Raven, The Tell-Tale Heart, The Pit and the Pendulum and The Black Cat. But they probably have not actually read any of his stories or poems since high school, if even then. Some of his 69 stories are comedies, and they have been forgotten entirely.

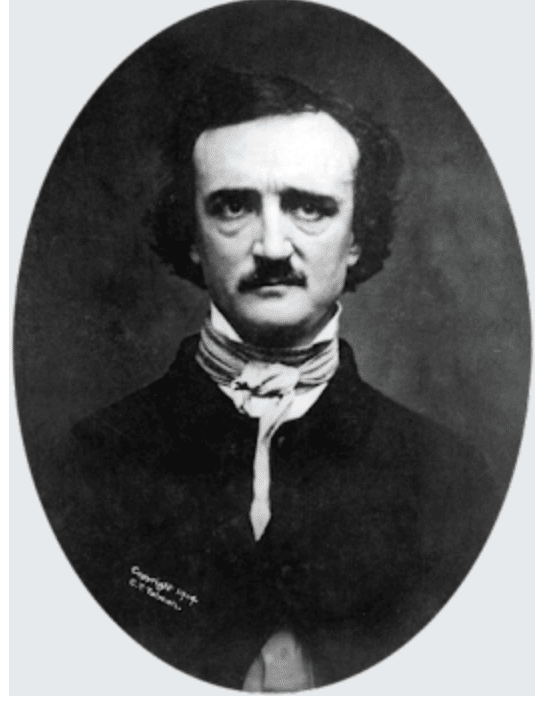

But it would be a poor Jeopardy contestant who would not recognize the famous photo of Edgar Allan Poe, which has graced everything from the Beatles’ Sargent Pepper album cover to thousands of websites. His little mustache, gigantic head, and sorrowful eyes seem to symbolize the terror of wrestling with internal demons and insanity while representing at the same time a literary genius that more than two centuries after his birth still make Edgar Allan Poe a literary icon.

Poe has been the subject of U.S. postage stamps, twice! There are Edgar Allan Poe tourist sites in New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, SC, and Baltimore, where he is so revered the football team was named after his most famous poem: The Raven.

The Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site in Philadelphia has the shadow of a raven on the walls in the late afternoon soon. Poe spent his most productive and happy years in the house immediately behind this, which is today a museum.

He was born on Jan. 19, 1809, to a pair of popular Virginia actors, David and Eliza Poe, but within two years his father ran off and his mother died. The orphan toddler was adopted by John and Frances Allan of Richmond, VA.

Despite his uncertain beginning, Poe considered himself a Southerner. So it is fitting that the Poe Museum in Richmond has the world’s largest collection of Poe memorabilia, including first editions, samples of his writing, family items, the small bed he slept in as a child (and perhaps had his first nightmares) and the trunk and other items surrounding his mysterious death.

A Rough Start

For someone whose adult life was as poor and tormented as Poe’s was, his life is remarkably well documented. Poe had a normal childhood in Richmond. He was an athlete and swimmer who enrolled at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. His room there has been preserved just as it would have looked in his day. When John Allan refused to pay the bills, however, Edgar began gambling, dropped out of school and at 18 ran away to enlist in the army under the name of Edgar A. Perry.

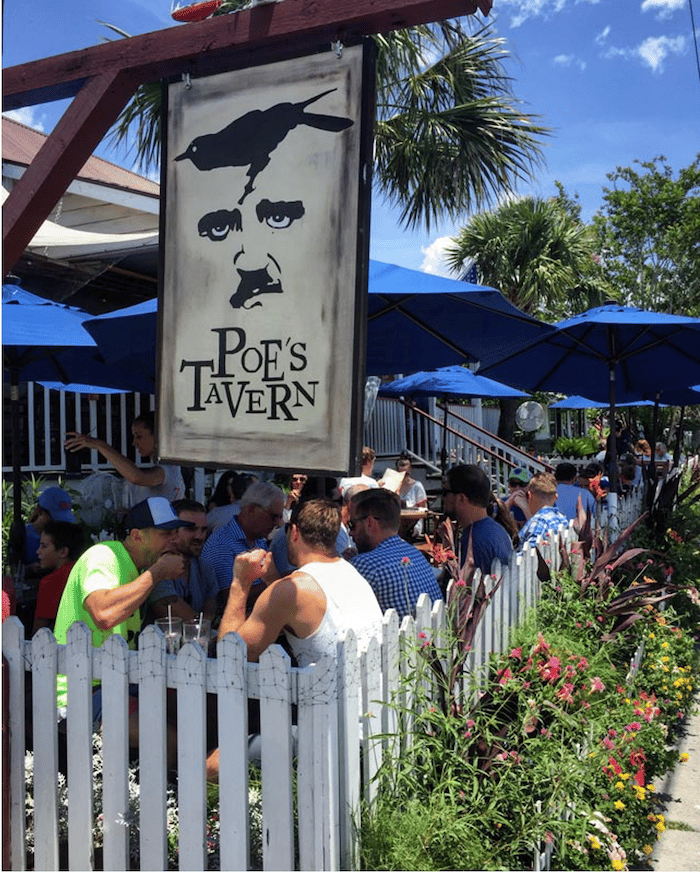

Fort Moultrie in Charleston, SC, takes pride in the fact that Poe served as a soldier here. Across the street from the fort is Poe’s Tavern, a lively pub filled with Poe memorabilia, photos and paintings. Incredibly, Poe was a good soldier. At least for a while. He was even accepted at West Point where the United States Military Academy still honors him with a stone arch, despite the fact that Poe eventually tired of the school’s discipline and deliberately earned enough demerits to be court martialed and expelled.

Poe’s dormitory room at the University of Virginia has been maintained exactly as it would have looked when he was a student here. Poe’s rooms actually never looked much different than this throughout his life due to his poverty.

Despondent, he took to writing poems and stories in Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger. In 1835, Poe published Berenice, his first tale of psychological terror. It’s a story about a man who becomes obsessed with his wife’s teeth. When she dies, he digs up the body, pulls out the teeth and keeps them like jewels in a box. Only later does he discover that his wife was prematurely buried and that her teeth mistakenly were extracted while she was still alive.

Tame by 21st century standards, perhaps, but it caused a sensation in 1835. The magazine’s owner was horrified. After all, when the Richmond Art Museum opened shortly before Berenice appeared, outraged citizens had broken in at night and put clothes on the nude statues.

But Edgar remained sanguine. “This is what people want to read!” he insisted. And he was right. The magazine’s circulation increased sevenfold. Despite the success, Edgar was fired.

Poe’s Tavern on Sullivan Island near Charleston, South Carolina is across the street from Fort Moultrie, where Poe was stationed when he enlisted in the US Army under a false name. Photo by Rich Grant

Raising Eyebrows

But Poe’s outward confidence masked a dark affliction. One drink would make him drunk and often incapacitate him for days. He was also a gambler and suffered from depression and melancholy. And then in Richmond he married his 13-year-old cousin. Even in an era where men married young women, this raised eyebrows.

The museum and most scholars present the case that when Edgar married his cousin Virginia, he was searching for a stable home life. He called his wife “Sissy,” (sister) and no one will ever know their true relationship. Whatever it was, he took his new wife, her mother, Maria Clemm, and a beloved tortoiseshell tabby cat named Catterina and settled into a strange household life in Philadelphia that was to change literature.

The Poe Museum in Richmond, VA. Be sure to look for two black cats that were born here and adopted by the staff. Named Edgar and Pluto (Pluto was the cat in the story “The Black Cat,”) they love to be petted and can be found in the garden and gift shop. Don’t worry, they have a nice home in the evening.

Poe In Philadelphia

If you visit only one Poe site, it should be Philadelphia’s Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site. He lived in this house during his most productive years from 1838 to 1844. At this time, Poe achieved fame from literary critics, including Charles Dickens. But his family lived in near poverty, surrounded by his alcoholism, misfortune and melancholy. While he accumulated thousands of dollars in gambling debts, he received just $10 for one of his most famous short stories, “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

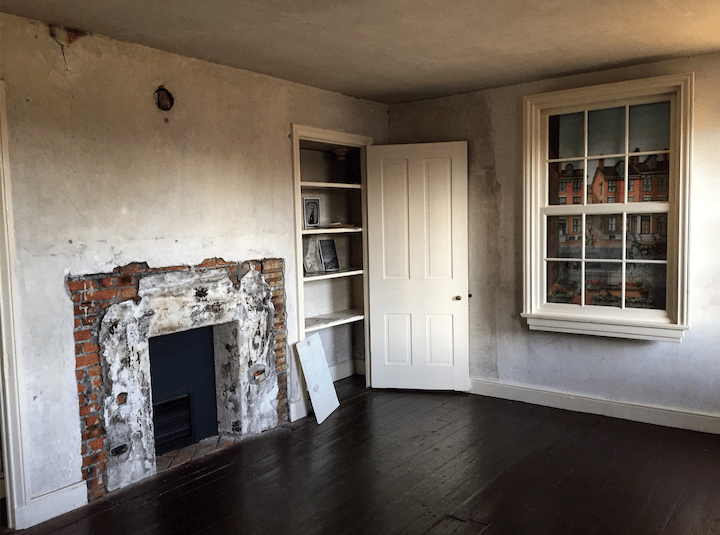

The brick house you see from the street was actually the house next door; Poe lived in the house behind it. But there’s no mistaking the large black raven statue in the yard, which casts an eerie shadow of spread black wings on the building every day in the late afternoon sun. Inside, on self-guiding or ranger-led tours, you tread the same floorboards as Poe and enter the depressing little rooms where he lived and worked.

Multi-media exhibits, timelines, photos and paintings try to create the atmosphere and desperation in which Poe wrote. Sadly, his wife Virginia developed tuberculosis and was ill for much of their time together. Poe at times sank into alcoholism and possible drug use. Which makes it hard to explain his productivity. Working 14 hours a day over a period of six years he wrote the first modern detective story, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, for which he was paid $56, and a number of classic tales of horror that include The Pit and the Pendulum (paid $38), the Tell-Tale Heart (paid $10), and “The Black Cat,” for which the Saturday Evening Post paid him a paltry $20.

The Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site in Philadelphia has preserved the room where Poe most likely wrote most of his stories. The window simulates what he would have seen looking across the street at this time.

Bedtime Reading

Poe’s The Mask of the Red Death still evokes gut-churning terror. The story centers on the rich king of a land beset by plague. The king takes 1,000 followers and locks them in a castle with special bolts and thick doors to keep away the disease. In the castle, they continue to party and ignore what is going on outside, until the last event – a masquerade party – where at midnight the revelers reveal their faces and to the horror of everyone present — one of them has the blood red spots of the disease.

For anyone who has not read Poe recently, The Black Cat is a good place to start. It is a haunting, horrible and unforgettable tale. The narrator is a man condemned to be hanged in the morning. He confesses that at one time, he was a loving husband with a black cat named Pluto who adored and followed him everywhere. But then he sank into alcoholism. One night, after coming home drunk in a rage, the cat bites him. In a fury, he seizes a penknife and cuts the cat’s eye out. And then the story becomes dark.

The tale, which Poe said was inspired by his Philadelphia house, ends in its basement with “a cry, at first muffled and broken, like the sobbing of a child, and then quickly swelling into one long, loud, and continuous scream, utterly anomalous and inhuman – a howl – a wailing shriek, half of horror and half of triumph, such as might have arisen only out of hell, conjointly from the throats of the damned in their agony and of the demons that exult in the damnation.”

Don’t miss the opportunity to go down in the basement and see what, and where, it happened.

Elfreth’s Alley, a historically preserved street in modern Philadelphia, gives some idea of what Philadelphia would have looked like in Poe’s time. The buildings here were constructed from 1728 to 1836. Photo by Rich Grant

It’s hard to imagine how thrilling his stories were to a public who had never read anything like them. The Black Cat came out the same year as Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. His dark stories of murder and madness were reprinted over and over, but in a day before copyrights, Poe was often not paid a penny beyond the initial sale.

Modern writers who are asked to write for “exposure” instead of cash will understand his frustration when in the 1840s he was given the exact same option. Some of his letters asking publishers for some payment other than a few copies of the book, are on display in the house. They are heartbreaking.

Despair and a Cottage in New York

As Virginia’s illness became worse and Poe’s instability increased, he decided they should move to the country north of New York for clean air. He rented a cottage for $100 a year in the village of Fordham in what was then Westchester. Poe’s Cottage is still there, and now a museum. However, it is no longer in the “country,” but is instead in the middle of the Bronx, across the street from a subway station and surrounded by high-density housing. It is just as interesting to visit the cottage to see how much New York has changed, as it is to continue Poe’s story.

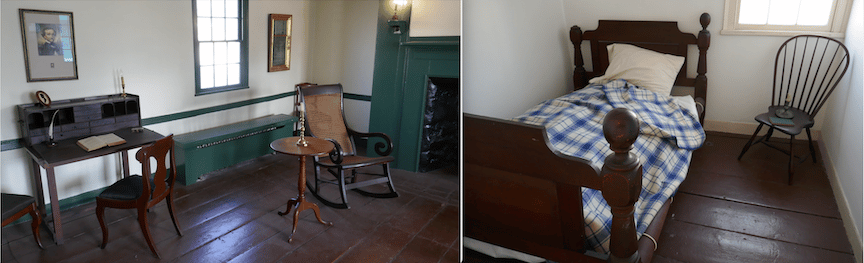

The cottage gives perhaps the best look at the poverty in which Poe lived. As you walk through the small rooms and up the creaking narrow stairs, the museum has three incredible Poe artifacts to ponder – Virginia’s poor rope bed, the plain rocking chair in which Poe must have spent hours sitting and writing, and a gilt-frame mirror – probably their only luxury. A visitor to the cottage remarked that on a cold day, poor Virginia had only Poe’s wool coat from West Point and their cat to keep her warm.

It was here Virginia died and a lonely Edgar Allan Poe slipped into alcoholic oblivion. The Raven was published while he lived here, giving him huge fame, and Poe became a tragic figure, known for taking long solitary walks in the woods around the neighborhood. Though in wretched shape, Poe still produced works such as the poem “The Bells,” inspired by the bells of nearby Fordham College, and short stories like The Cask of Amontillado, and Hop-Frog, the demented fable of a king’s jester that has become a classic of the macabre.

Poe’s Cottage in New York was at one time in the country but is now surrounded by high density housing in the Bronx and across the street from a subway station, showing how much the city has changed. Photo by Rich Grant

A Mysterious Death in Baltimore

Befitting the rest of his life, Poe’s death is a great mystery. He hoped to publish a literary magazine and went to Philadelphia to discuss it, before heading on to Richmond. What happened after, no one knows. He left Richmond on Sept. 27, 1849, bound for New York. On Oct. 3, he was found on the streets of Baltimore, delirious with unkempt hair and wearing soiled clothes that did not fit him and appeared to belong to someone else. Taken to hospital, he died four days later without gaining consciousness. He was just 40 years old.

Various theories, from murder and suicide to cholera, hypoglycemia and alcoholism have been advanced. Baltimore’s oldest operating saloon, The Horse You Came in On, goes so far as to claim it has a stool where Poe sat and had his last drink. Very doubtful, but it is a good story, and the bar’s location in Fell’s Point is certainly the highlight of any visit to Baltimore.

The city makes great claims on Poe. The house he lived in with his aunt Maria and cousin and future wife, Virginia, is here and open as the Edgar Allan Poe House & Museum. Though unfurnished, the house is unchanged and now offers exhibits on the writer’s early life where he first met and fell in love with Virginia.

A short distance away, in the pretty graveyard behind Westminister Church. The three household companions, Edgar, Virginia and Maria, are all buried together, at peace at last.

The USS Constellation in Baltimore Harbor was actually built four years after Poe died in 1853, but is the geographic center of the city. From here you can take a water taxi (small vessel bottom right) to Fells Point, where Poe died under mysterious circumstances. Photo by Rich Grant

Following the Trail

One of the best things about following the Edgar Allan Poe trail is that his life involves nearly the entire Eastern seaboard and he lived near wonderful things to see.

The Poe Museum in Richmond was started in his honor in 1906 by Poe collector and scholar, James Howard Whitty. It is located in the oldest house in the city, in the historic Shockoe Bottom district, near St. John’s Church where Patrick Henry gave his famous “Give Me Liberty” speech. Don’t miss the two black cats that live on the property and love to be petted.

The University of Virginia was designed by Thomas Jefferson and is one of the nation’s most gorgeous campuses.

Fort Moultrie in Charleston was the site of a large battle in the American Revolution. Poe would have absolutely loved the Poe Tavern, one of Charleston’s most popular pubs, that now sits across the street.

Few spots offer as much natural beauty as West Point, which is located at a strategic bend of the Hudson River. Visitors can see the same view Poe saw.

In Philadelphia, the Poe historic site is just two blocks from Yards Brewery, the perfect place to stop and sample 20 craft beers on tap, and a true Philadelphia specialty – the soft pretzel. History lovers will want to try a taster tray of Revolutionary ales: three historic beers made from recipes originally owned by George Washington, Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson.

New York’s Poe Cottage is easy to reach on the D subway, and is only 15 minutes from D subway stops along the western edge of Central Park. From the cottage, it is just a short stroll to Fordham University, where Poe went on many walks.

During the long months of winter, Edgar Allan Poe spent many hours rocking beside the fireplace with the gilt frame mirror behind him the only thing of value in the modest house. The rope bed in the tiny bedroom on the right is where Poe’s wife Virginia died after a long illness with tuberculosis. Photos by Rich Grant

Fells Point in Baltimore, near where Poe was discovered unconscious, is one of America’s most exuberant neighborhoods, filled with historic buildings, taverns, crab houses and cafes. The most picturesque way to arrive is by water taxi from Baltimore’s main harbor. The name of Baltimore’s football team, The Ravens, was selected by a popular vote of the people in 1996, with The Ravens receiving more than four times as many votes as the other choices.

Poe’s grave is as famous for the Poe Toaster as it is for Poe. For 50 years –from 1949, Poe’s 150th birthday, to 2009, his 200th — someone appeared on Poe’s birthday in a wide brim hat and white scarf, have a toast of cognac, leave the bottle and three roses on the grave and then disappear into the night. Despite many attempts to catch him (or her), no one knows who it was. Since 2009, imposters have tried to revive the tradition, but the real Poe Toaster disappeared, perhaps appropriately, about the same time cell phone cameras took off and the world lost some of its mystery.

Some things are best left to legends. Like the basement of the Black Cat, the bar stool where Poe had his last drink and the events preceding his death. Are the night terrors his writing still inspire real or the fevered figments of imagination? Read Edgar Allan Poe on a stormy night and discover for yourself.![]()

Rich Grant’s previous stories for EWNS profiled Deadwood, South Dakota and the Philadelphia of George Washington.