For the better part of three years Macau slumbered, its public squares subdued, its major shopping streets shuttered. On two occasions the entire city locked down on orders from Beijing. For a city of 713,000 that makes all its money selling the luck of the draw, the consequences of reduced tourism were severe. Annual gambling revenues for 2022 were $5 billion, down from a pre-Covid high of $45 billion.

Recovery coincided with the elimination of China’s Zero Covid policy. More people visited Macau in the first nine months of 2023 than in the preceding three years combined. Today, the city is on pace to earn over $30 billion by the end of 2024. Las Vegas, by comparison, has annual gaming revenues of $8.9 billion.

When I visited Macau on a weekend near the end of 2023, jetfoils packed with Hong Kong Chinese were pulling into the ferry terminal every 15 minutes. One mile north at the land border with China, new arrivals were elbowing their way toward customs checkpoints in a hall longer than a football field. By 9:00 p.m. visitors were arriving at the rate of 16,000 an hour. Few carried much luggage since most planned to stay less than a day and spend almost every minute gambling.

Beyond the immigration checkpoint stands a modest arc de triumph built by the Portuguese in 1870 that once served as the main border crossing. But few Chinese glance at the colonial remnant, now dwarfed by China’s massive new facilities. Their eyes are focused on dozens of hospitality buses that stand by around the clock to whisk new arrivals to one of the city’s 31 casinos.

Outside the Wynn Macau, an artificial lake is roiling with bursts of flame and “Luck Be A Lady Tonight” echoes through the porte-cochère. Inside, however, it’s clear this Wynn resort is no Vegas clone. There are no scantily attired waitresses serving drinks. Refreshment mainly consists of mango nectar and lemon squash served off a trolley by middle-aged women in brown pantsuits. Neither can you find lounge singers or comedians. At the Wynn, Macau the main attraction is gambling.

Macau is the only entity on the Chinese mainland where gaming is legal.

The Venetian Casino, hotel, shopping center and exhibition halls are on the Cotai Strip, a 2-sq mi piece of reclaimed land between Taipa and Coloane islands. Photo by David DeVoss

It’s almost midnight when I leave the casino, but outside the night sky glows in neon twilight. In the distance, dozens of buses crawl slowly across three massive suspension bridges to entertainment hotspots on islands that were largely rural three decades before. Below a subterranean expressway, pedestrian tunnels and parking garages, all recently carved out of land reclaimed from the South China Sea, hum with activity.

The streets are full of Chinese, few of them old enough to remember Mao’s decade-long Cultural Revolution. These are the grandchildren of Mao, pampered products of one-child families raised under a capitalistic form of communism.

Across the street at the Galaxy casino, statuesque Asian models in cheongsam miniskirts hired for their flawless beauty and abnormal height greet gamblers walking through the door. Nearby, a knot of revelers flush with winnings from the MGM Casino throw strings of firecrackers in celebration. Ahead looms the Bank of China. Clad in granite and guarded by two snarling stone lions, the bank symbolizes the communist party of China’s rigid central planning. Yet here the Bank of China stands right in the middle of Party Central next to the giant lotus casino, just one of Macau’s many ironies.

Everybody feels welcome after a Galaxy Casino greeting. Photo by David DeVoss

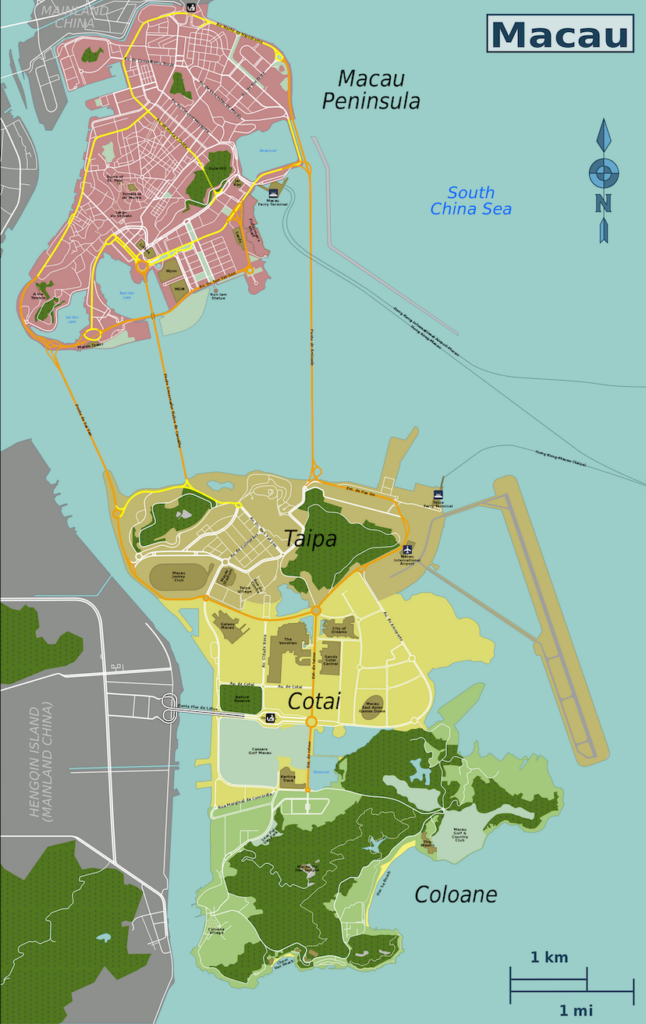

I first came to Macau 45 years ago to report a story about organized criminals called triads, who were responsible for much of the city’s violent crime and loan sharking. Macau was tiny, consisting of a peninsula one could walk across in 20 minutes plus two small islands called Taipa and Coloane. The city was built on seven hills, each topped by a church or fortress, all of them connected to a colonial town square by cobbled sidewalks inlaid with images of cathedrals and caravels.

Unlike Hong Kong, where development trumped history, Macau seemed dipped in amber. Brightly painted shops that once served as brothels ran the length of Rua da Felicidade. Around the corner on Travessa do Ópio stood an abandoned factory that once processed opium. The early 19th-century mansion built by British merchants of the East India Company was still there, as was the rocky grotto where Portuguese poet Luis Camões in 1556 began composing Os Lusiadas, an epic tale of Vasco da Gama’s explorations of the East told in a manner similar to Virgil’s Aeneid.

Brightly painted shops that once served as brothels ran The brothels are closed on Macau’s Rua da Felicidade, but the red doors and windows remain in a nod to the city’s storied history. Photo by David DeVoss

Macau usually was described as “a decaying bastion of Portuguese colonialism.” Residents charitably described it as “sleepy.” The colony’s only exports were fish and firecrackers. In 1975, Lisbon had walked away from its territories in Angola, Mozambique and East Timor. Portugal also tried to give Macau back to China but was rebuffed by Beijing, which declined to accept it. In theory, Portugal still remained in control of Macau, but the Portuguese priests, civil servants and army officers living there seemed content to take long lunches and allow their colonial enclave to drift aimlessly.

Most of what I first knew about the place came from the movie Macao, a campy knockoff of Casablanca starring Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell that I’d seen on a vintage film night in college. The Europeans wore white linen suits; the Chinese threw knives; Jane Russell breathed deeply and depended on the kindness of strangers. I remembered the movie only because of its tagline: “A sultry chanteuse, a hunk on the lam and a fortune in stolen gems.”

Incense swirls throughout the day at the A-Ma Temple in Macau. Photo by David DeVoss

Macau’s Portuguese police, who wore trench coats, rolled their own cigarettes and acted a lot like Robert Mitchum, allowed me to tag along on what was described as “a major triad sweep.” But after several desultory brothel inspections they grew tired of the game and headed for the Lisboa Casino, a refurbished but still seedy place where men in stained singlets placed bets alongside chain-smoking prostitutes from China.

The Lisboa belonged to Stanley Ho, the richest man in town thanks to his government-sanctioned gaming monopoly and his control of the ferries linking Macau with the outside world. According to British authorities, Ho’s rise to power was aided by a Hong Kong gangster named Yip Hon. Macau’s triads even had a nickname for Ho, Sun Goh, which translated as New Brother. But Macau’s police had no interest in pursuing Ho, who had used his wealth to become the city’s leading benefactor.

Two decades later, on the eve of the territory’s 1999 return to China after 443 years of Portuguese administration, the city remained much the same. Despite the presence of 11 casinos, annual arrivals numbered only seven million. Hotel occupancy barely exceeded 50%. Gangland murders occurred with numbing regularity. Macau had a GDP lower than Malawi.

In 2002, the dynamics of Macau finally began to change when China ended the 40-year-old gaming monopoly and allowed five outside concessionaires, three of them American, to compete with Ho to build mega resorts and casinos reflective of China’s new wealth and power. Beijing also made it easier for increasingly affluent Mainland Chinese to enter Macau and other special administrative regions and economic zones operating under the “one country, two systems” philosophy.

Religion is discouraged throughout most of China, but in Macau Catholicism is allowed to exist. The Holy House of Mercy flanks Senate Square, the obvious location for a political rally were any ever held. But having watched recent events in nearby Hong Kong, Macanese know to keep their opinions private. Photo by David DeVoss

So many Mainland Chinese flocked to Macau to see the opulent American casinos that 12 months after its opening, the Las Vegas Sands Corp. had recouped its entire $245 million investment and earned enough profit to start building the $2.4 billion Venetian Casino and Resort Hotel on the Cotai Strip, the two square miles of landfill linking the islands of Coloane and Taipa.

Today Cotai is home to 13 of Macau’s most elegant resort properties. The largest is a $4 billion development the focal point of which is The Londoner Hotel recognized by its Houses of Parliament facade and scale replicas of Big Ben and Lord Nelson’s Trafalgar Column. It has a casino, but families will spend most of their time in the 3,000 sq. meters Harry Potter exhibition with interactive Hogwarts portraits, enjoying refreshments served by Alice in Wonderland impersonators or watching a Changing of the Guard in the Crystal Palace with dancing Beefeaters, twirling Bobbies and soldiers in bearskin hats.

Once the children are exhausted, parents can sneak off for a Victorian afternoon tea followed by a virtual tour of London in a Black cab accompanied by a David Beckham hologram.

Alice in Wonderland comes alive at The Londoner on the Cotai Strip in Macau.

Slightly north of The Londoner is The City of Dreams where you’ll find The House of Dancing Water Show, a $250 million production that features gravity-defying stunts and costumed acrobatics performed in, on and above a pool holding 3.7 million gallons of water and 239 jets shoot water. Initially, the show seems akin to an aquatic Cirque du Soleil, but the sheer audacity of the breathtaking stunts quickly set it apart.

Macau is a small place (just 12.7 sq mi) with excellent public transportation. Over a long weekend, it’s possible to see all of the museums, old temples, churches and fortresses. But don’t forget the Macau Tower, a slender spire soaring 338 meters above the city.

Yes, cities from Seattle to Shanghai have “Space Needles” with revolving restaurants and 360-degree photo platforms. But in Macau, tethered brave hearts can go outside and walk around a narrow Skywalk that has no handrail. If this fails to get the adrenaline pumping, for a few dollars more it’s possible to bungee jump off the deck and plummet to earth at 200 km/hour before being jerked back

Chinese Madonna and Child. Jesuits won early converts in Macau by changing traditional Christian iconography into more identifiable images. Photo by David DeVoss

The Portuguese once called Macau “The City of the Name of God in China, No Other More Loyal,” after the Ming Dynasty Emperor Shizong allowed them to set up an outpost here in 1557. Jesuit and Dominican missionaries arrived to spread the Gospel, and merchants and sailors followed.

The Jesuits opened the College of Madre de Deus in 1594 and attracted scholars from throughout Asia. By 1610, there were 150,000 Christians in China, and Macau was a city with Portuguese mansions in the hills and Chinese living below.

In 1630, the Portuguese completed St. Paul’s Church, a massive house of worship that became the grandest ecclesiastical structure in Asia. St. Paul’s accidentally burned in 1835 leaving little beyond its façade, but by then Macau was largely a Chinese city with concerns other than Catholicism.

“Every night Macau sets out to have fun,” French playwright Francis de Croisset observed after visiting the city in 1937. “Restaurants, gambling houses, dance halls, brothels and opium dens are crowded together, higgledy-piggledy.”

“Everybody at Macao gambles,” he noted. “The painted flapper who is not a school girl but a prostitute, and who, between two brief spells of dalliance, wagers as much as she can earn in a night; the beggar who has just managed to cadge a coin and now, no longer cringing, stakes it with a lordly air; and finally, the old woman who, with nothing left to wager, to my astonishment took out three gold teeth, which, with a gaping smile, she staked and lost.”

Macau’s economy still is dominated by gambling, but the casinos have no claim on the city’s soul. “Once this was the most beautiful building in Asia,” says Macau historian Jorge Cavalheiro, as he guides me past the remains of St. Paul’s church. “It had relics and treasures, but most were removed over the centuries because of typhoons and fires.”

Facade of St. Paul’s church. Photo by David DeVoss

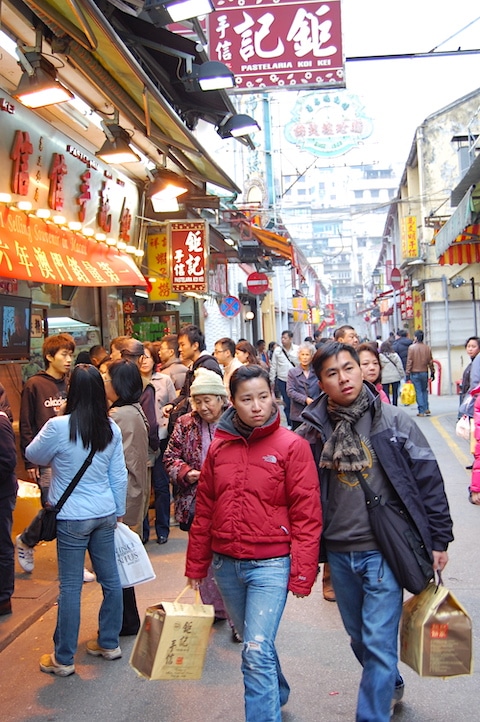

It’s Saturday afternoon and we’re surrounded by thousands of tourists as we stroll through the middle of Portuguese Macau. At St. Dominick’s Church, we veer to the right and enter Senate Square where black and white cobblestones are arranged to resemble waves arriving onshore. Located in the center of Macau and dating back over 400 years, the square is surrounded by colonial buildings only two of which dominate: the Loyal Senate, which was the seat of secular authority, and the taller, more elaborate symbol of Catholic charity, the Holy House of Mercy. “Prior to the transition I worried about the fate of Portugal’s patrimony, but it seems China intends to protect our old buildings,” Cavalheiro smiles.

But as we walk toward St. Joseph’s Church, where a purported fragment of St. Francis humerus is enshrined, it’s apparent Portugal’s real patrimony can be found in the Macanese people, who have faces reflecting a diverse Asian heritage and surnames like Gomes, Lourenco and Oliveira. Indeed, Macau retains the spirit of the past in ways seldom seen in Ho Chi Minh City or Jakarta where one searches in vain for signs of France’s mission civilisatrice or Amsterdam’s burgher mentality. St. Francis never got to China, but his spirit lives on in Macau.

Macanese shoppers near Senate Square shop for Chinese New Year gifts. Photo by David DeVoss

Not all Macau residents are pleased with their city’s transformation. When Henrique da Senna Fernandez, an 84-year-old lawyer, looks out the window of his office building on what once was Macau’s Pria Grande, he sees a forest of casinos and banks, not the languid quayside. “The sea used to be here,” he sighs, looking at the sidewalk below. “Now all the fishing junks are gone, and Macau is just a big city where people only talk about money.”

In Macau glitz rules whether it’s the solid gold bars embedded into the acrylic lobby floor of Macau’s Grand Emperor Hotel or the Wynn Casino’s Tree of Prosperity. The tree is covered in 24-karat gold and surrounded by gilded boulders. The 33-foot tree appears twice an hour on a pedestal that rises from beneath an atrium floor to bathe the gold in laser light.

The Tree of Prosperity at the Wynn Casino embodies the average citizen’s hope for wealth and security. Photo by David DeVoss

Next to the Tree of Prosperity is a hallway lined with shops selling luxury goods. Those shops with monthly sales in the millions may be the most profitable commercial real estate in the world. Says one Hong Kong-based foreign diplomat who travels to Macau regularly: “Westerners who come here cross into China to buy fakes while the Chinese come here to buy the real stuff.”

Macau is improving its infrastructure to make it easier for visitor arrivals. The airport that opened in the 1990s has doubled its capacity. An elevated bridge linking Hong Kong, Macau and Zuhai means tourists in Hong Kong can Uber to Macau if they don’t want to take a jetfoil. And with 2.4 billion people living within a five-hour flight of Macau, it’s a certainty that people will continue to come. Says Correia da Silva: “Macau should sell itself like the Muslims sell Mecca: a city that must be visited at least once in a lifetime.”

_____________________

David DeVoss is editor & senior correspondent of the East-West News Service.