By David DeVoss

The greatest journey in life is the one we all take to the grave. It’s a trip where getting there is all of the fun. Along the road travelers encounter luxury hotels, memorable dinners, historic athletic contests and a bucket list of exciting experiences. For those who invest wisely and are prudent with their savings, the last leg of life can be filled with glamping safaris and Disney cruises with the grandchildren. Yet travel writers rarely ponder humanity’s final steps toward the ultimate threshold.

Iowa journalist and Society of American Travel Writers member Lori Erickson is the exception for in her new book, Near the Exit, she explores what lies at the end of the road and discovers that the specter of death is more human than horrid.

Her travels take her from the subterranean tombs of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings to the necropolis in Rome with intermediate stops at a Day of the Dead celebration and New Zealand, where she learns the relationship the islands’ Maori have with their ancestors. She even attends a cocktail party in a graveyard.

To her credit, Erickson does not shy away from hospices and nursing homes, which she calls “God’s Waiting Rooms.” She finds the one where her mother lives “surreal, poignant and amusing, all at the same time.”

Americans today over the age of 65 have about a one-in-four chance of spending their final days in a nursing home, which Erickson concedes can be more warehouse than home. But in a society where grandchildren and daughters no longer have the time to care for the elderly, nursing homes are necessary. “To do what the nursing home staff provides for my mother, I’d have to quit my job and still hire additional help,” she concludes. “Visiting her, I’m struck by how amazing it is to have twenty-four-hour care facilities for the elderly.”

Erickson largely avoids theosophical issues, preferring a lighter narrative that focuses on travel to places we all will pass through eventually. As a deacon in the Episcopal Church, she often is asked to give eulogies at funerals, events she describes with the insight of a trained observer, arguing that people shouldn’t go gently into that good night.

“After my death, I’ve toyed with the idea of having a send-off inspired by my Viking ancestors,” she writes. “I do like the idea of having my corpse and my most precious possessions put into a longboat, which would be set out to sea and then set afire by a flaming arrow fired by one of my sons from shore. The expense of this is daunting, however, as well as the fact that live more than a thousand miles from an ocean.”

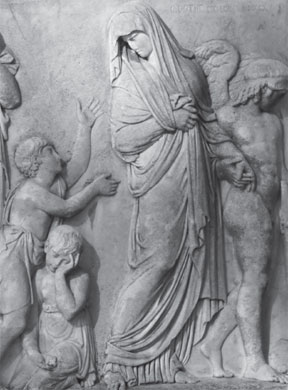

In Italy, Erickson travels to place you probably never have been. She begins with a search for the remains of St. Peter, said to lie beneath his eponymous basilica. Spending a sunny afternoon in an underground Necropolis is not the way most tourists envision their visit to Rome. But walking past small crypts many bearing images of Egyptian gods and Roman frescos certainly evokes images more central to Roman identity than sidewalk cafes and three-hour lunches.

“At last, we came to our destination: the place where Peter’s remains are kept in a clear box tucked into a crevice in the rock wall,” she confides. “All that was visible was a small glimpse of bones”.

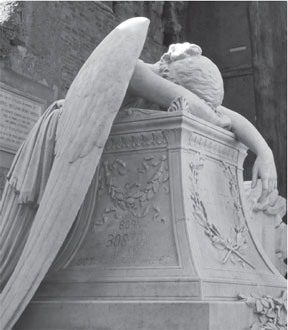

Erickson encounters images of death in almost every place she goes in Rome: at the Vatican, inside the Coliseum, astride the Appian Way and across the Protestant Cemetery where nineteenth century poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats are buried. “Rome is so comfortable with death because it’s steeped in Christianity, a religion that emphasizes resurrection,” she surmises.

“Standing by his grave, I thought of all the ways people try to ensure that they’ll be remembered, from long epitaphs and grand mausoleums to commissioned portraits. I had read many markers with variations of “Never Forgotten,” a statement made with the best of intentions but nearly always thwarted by the passage of time. Keats teaches us that earthly

immortality isn’t something we can orchestrate. Even if we place our tombs next to busy thoroughfares and have our likeness sculpted in marble, the odds are good that we’ll be forgotten. ’Tis best to let time sort out who gets remembered and who doesn’t.

When Oscar Wilde—ever a fan of extravagant gestures—visited this cemetery in 1877, he prostrated himself at Keats’s grave, calling it “the holiest place in Rome.” Forget the pagan temples, the Vatican, and the many churches in the city—instead, he found the sacred here, at the grave of a young man he’d met only through his words, which turned out to be immortal after all.”![]()

Near the Exit

Lori Erickson

Westminster John Knox Press

2019, pp. 171

ISBN-13: 9780664265670

David DeVoss is editor and senior correspondent of the East-West News Service