Tourists visiting Bergen flock to Bryggen’s colorful waterfront, gable-roofed buildings filled with shops, galleries and restaurants. Photo by Richard Varr

By Richard Varr

It doesn’t take long for a sense of history to overwhelm you when walking through the narrow passageways of Bryggen’s wooden warehouses. Yes, the building facades are immaculate, swashed with muted red and brown earthen hues, but every step on wooden plank floors and stairwells seemingly comes with a creak or two, like the infrastructure is grunting with old age.

Bryggen, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a must-see in Bergen; if you’re down by the waterfront, you can’t miss it. The colorful warehouse district, now teeming with galleries, restaurants, boutiques, and no shortage of tacky tourist shops, dates back to the Middle Ages when Bergen was a booming trade port supplying dried fish from Norway’s northern coastline to many cities in Northern Europe. The district was a working hub for the German-based Hanseatic League trading company.

If you ask the locals, that history has resulted in the shifting foundation with creaks and groans, and with obvious cracks under constant repair. And why is this?

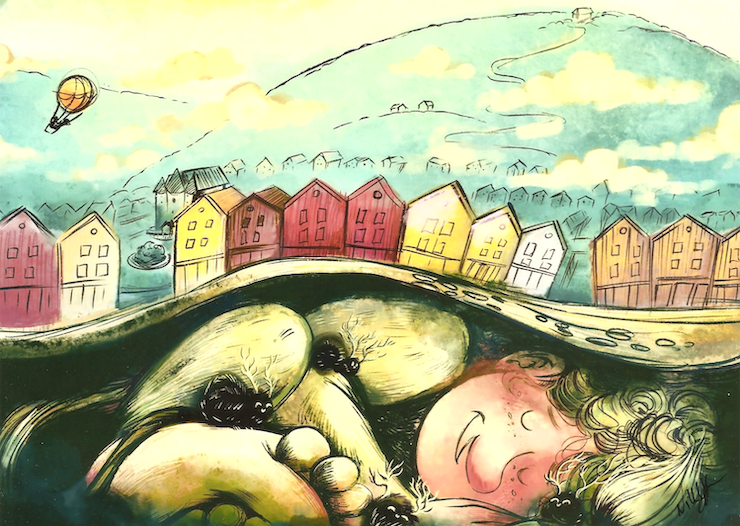

A Bergen artist revealed her thoughts in one of her drawings – a smiling troll sleeping snuggly under the waterfront. “What’s the story with the crooked houses?” asks artist Nille Horgen whose paintings and drawings hang in her gallery HUG Bryggen. “It’s because a sleeping troll is underneath and when he turns over the houses tend to move.”

Her humorous theory highlights what those who work here have experienced through the years. “Because when you have a gallery here, you notice changes with every season,” says Horgen. “You look at the frames; they continuously move. So, with the sleeping troll, I thought it would be entertaining and historic as well.”

Bergen artist Nille Horgen created this drawing showing a sleeping forest troll under Bryggen as the reason why the buildings creak and shift. Drawing courtesy of Nille Horgen.

Centuries of Fires and Rubble

The real reason for the unstable foundation, however, is that multiple fires have razed the warehouses over the centuries. With each blaze, waterfront rubble was pushed into the water with the warehouses rebuilt on top of the new and added shoreline. “It rains a lot on the wood and that’s why everything is so squishy,” adds Horgen.

“The waterline and harbor used to be farther back,” explains Celine Weisenfeld, a guide with the Hanseatic Museum and Schøtstuene. “Every time Bryggen burned down, they rebuilt it the same way as it was before but slightly farther into the water,” she adds while pointing out an actual foundation crack in one building façade.

The latest Bryggen reconstruction dates back to after the Great Fire of 1702, with some of those original buildings remaining today. Colorful waterside gabled facades front the long rows of wooden warehouses called tenements that sit side by side, with some entrances leading to the narrow alleyways between them.

In warmer weather – especially when cruise ships are in port – visitors flock to the outdoor cafes and the tables and bars of adjoining restaurants facing the harbor. The facades are reminiscent of Copenhagen’s idyllic Nyhavn Canal, especially popular for its Christmas markets, or even Curacao’s string of Dutch colonial waterfront homes in Willemstad with their brilliant blue, yellow and pink hues aglow in the Caribbean sun.

Long narrow corridors and alleyways now lined with shops separate the restored and rebuilt warehouses at the Bryggen waterfront. Photo by Richard Varr

A Powerful Medieval Trade Alliance

The Hanseatic League established trade routes among Scandinavian and Northern European ports from the 12th to 17th centuries, peaking from the 13th to 15th centuries, and stretching from modern-day England to Russia. Formed to strengthen trade and protect against pirates, German merchants established the league, creating trading posts at upwards of 200 cities and medieval settlements.

Bergen was a key port for shipping stockfish and cod liver oil from the bountiful fishing grounds of northern Norway in return for commodities including grain, cloth, furs, metal ores, spices and beer, to name a few. The plentiful cod was easily dried and preserved, making it safe for shipping long distances.

The Hanseatic merchants’ way of life in Bergen comes to life at Bryggen’s Hanseatic Museum and Schøtstuene. German merchants came and went, living and working at Bryggen for several years at a time before returning home. At a different location than the waterfront museum, the Schøtstuene comprises mostly what were administrative buildings with four assembly rooms and two cook houses painted in red and brown earthen colors. A few of the original structures date back to 1703 and 1709, while the others are reconstructions from 1938 with dates marked on each building. Inside, simple wooden benches and tables line the assembly rooms providing a glimpse of how they looked during their use, while pots and utensils hang from kitchens with makeshift food displays.

The museum building along the waterfront has been closed since 2018 and will likely stay closed until 2027, itself a victim of a wavering wooden foundation which is being replaced. “It sank into the ground and they have to lift the whole building up again and fix the foundation,” says Weisenfeld.

Medieval shoes in the Bryggen Museum are in surprisingly good condition. The shoes were unearthed after a fire destroyed the harbor-front buildings in 1955. Photo by Richard Varr

A Window to Bergen’s Medieval Past

A modern day fire opened a window for a close-up look at life in medieval Bergen. The blaze ripped through the harbor area in 1955, resulting in a 13-year archeological dig unearthing thousands of artifacts. They’re housed in the Bryggen Museum built atop where some of the oldest buildings once stood. The foundation ruins of those buildings make up a key exhibit on the museum’s lower floor. Glass and steel walkways stand above stones and splintered wooden floorboards dating back to the 1100s.

Glass cases housing ceramic jugs and cookware testify to the extent of the Hanseatic League’s European and Middle Eastern trade routes. Metal spoons, forks and plates fill other displays along with medieval half-penny and English sterling coins. Combs, well-preserved shoes and centuries-old jewelry round out the collection. A key artifact is a sturdy wooden beam believed to be from the hull of a more than 100-foot-long merchant ship.

When the port was key in supplying fish to Northern Europe, hungry locals once flocked to the city’s Fish Market established in the 1500s. Today, a string of eateries now stands on the same spot at the harbor’s base where tourists and locals dine in tent-like settings serving up the likes of salmon burgers, fish soups, cod plates and reindeer sausage.

Bergen’s main square is centered with the Seafarers’ Monument which pays tribute to sailors from the 10th-century Viking era up to Norway’s modern-day seamen. Photo by Richard Varr

A short walk from the fish market, the Seafarers’ Monument sits at the start of Bergen’s main square. Statues atop the block-like monument pay tribute to sailors from the 10th-century Viking era through colonial exploration and whaling, and up to Norway’s modern-day seamen. Viking and other model ships fill Bergen’s Maritime Museum, while the Norwegian Fisheries Museum further explores this seafaring heritage.

Bergen and the Great Outdoors: Mountains, Waterfalls and Fjords at Every Turn

The dramatic sweeping view of Bergen’s harbor and waterways as seen from atop Mount Fløyen. The peak is reached by riding the Fløibanen Funicular, a short walk from the waterfront. Photo by Richard Varr

A good way to see the dramatic waterways and towering mountains around Bergen is from above. A ride up the Fløibanen Funicular, just a short walk from the waterfront, shoots up more than 1,000 feet to the top of Mount Fløyen for stunning views of the city and harbor. Hiking trails weave through the surrounding forest and provide a path down the mountain and back into town taking about 45 minutes. For lunch or dinner, the upscale Fløirestaurant next to the funicular offers menu choices including Norwegian oysters, yellow beetroot tartar, venison and fish soup. No charge for the sweeping views.

Bergen is the launching port of call for both Hurtigruten and Havila Voyages cruises navigating north in and around the islands and fjords of Norway’s dramatic west coast. It’s also the starting point for the so-called Norway in a Nutshell day tour which includes taking trains through mountainous terrain and a boat ride on the twisting Nærøyfjord. A visit to the village of Flåm with its tumbling waterfalls and narrow valleys occurs about midway through the tour.

About 70 miles to the north is Norway’s “King of the Fjords,” Sognefjord, which meanders deep into the countryside. Several smaller fjords branch out from the waterway through the mountainous snow-peaked landscape dotted with waterside villages. The “Queen of the Fjords,” Hardangerfjord, flows 112 miles southeast of Bergen. Day trips include boat cruises and hiking trips.

Oslo: Art and Culture

Interactive screens detailing the lives of some of the most notable Nobel Peace Prize awardees in Oslo’s Nobel Peace Center’s key exhibit room, The Nobel Field. Photo by Richard Varr

Oslo hugs the eastern shores of lower Norway, a seven-hour train ride from Bergen through some of the country’s most scenic landscapes. While Bergen’s fishing heritage and natural wonders give it a more traditional feel, Oslo’s art and culture give Scandinavia’s progressive capital an edgier, cosmopolitan vibe.

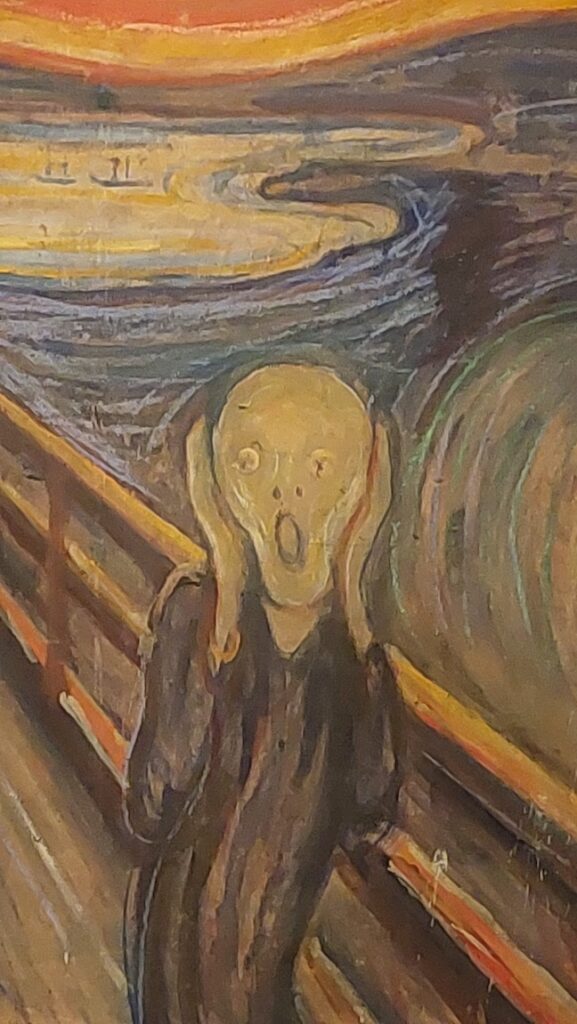

The Scream helps define Oslo’s cultural soul. It’s the world-renowned painting by native son Edvard Munch and the centerpiece of Oslo’s 12-story Munch Museum. In fact, the museum has several versions of the artwork of a seemingly hysterical figure with mouth agape against a swirl of bright hues depicting a dramatic, red-toned sky. The museum houses about 1,200 of Munch’s paintings, many portraying themes of anguish and isolation.

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s The Scream in Oslo’s National Museum. Photo by Richard Varr

Other city locations fronting his works include the University of Oslo, the National Museum and Oslo City Hall which houses his painting titled Life. “This painting has very bright colors with a happy theme and celebrates life and different generations coming together, while other paintings by Munch have darker colors and darker themes like illness, death and depression,” explains City Hall guide Victoria Nunes Finstad.

Close to Oslo’s harbor with its bustling waterfront is the Nobel Peace Center. Located in a former train depot, it pays homage to the world’s 1,000-plus Nobel Peace Prize recipients. In the museum’s main exhibit room, hundreds of interactive screens resting atop thin poles detail the lives of some of the most notable awardees.

The actual ship Fram on which arctic explorer Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole in 1911 sits inside Oslo’s specially designed Fram Museum. Photo by Richard Varr

Norway’s seafaring past and traditional lifestyle are also celebrated in Oslo. From the harbor, a ferry chugs across the Oslofjord bringing passengers to the tip of the Bygdøy peninsula with its prominent maritime-themed museums. Most notable are the Museum of the Viking Age with its seemingly ageless Viking ships and the Fram Museum which displays the actual ship on which Roald Amundsen began his exploration of Antarctica. The race to the Pole ended in 1911 with Amundsen being the first to arrive.

Trolls: Myth and Folklore, Right?

A troll clutching a walking stick stands at the doorway of a Bryggen tourist shop. He’s maybe two feet tall with a long nose, a drooping gut and oversized hands and feet. He seems friendly enough, catching the eye of curious passersby. Of course, the troll is just a prop, modeled after what Norwegian folklore dictates.

But if you look diligently you’ll find that trolls are all over Norway. Their faces appear on mysterious rock formations on cliffs, in paintings and on book covers. Figurines with contorted body shapes are for sale as trinkets. So maybe it’s not so hard to imagine a troll could be sleeping under Bryggen and causing the buildings to creak and shift.

A wooden troll figurine outside a tourist trinket shop along the Bryggen waterfront. Trolls and fairies are a popular part of Norwegian folklore. Photo by Richard Varr

“As a local, I would say it’s more of a tourist thing,” says Ronja Valaker, a guide with the Hanseatic Museum and Schøtstuene. “Trinket shops have found it appeals to tourists, so they’ve created troll souvenirs.”

“Yes, rocks do have faces as they were once trolls who turned to stone,” she smiles. “But they can wake up again.”![]()

Richard Varr is a former newspaper and television reporter who lives in Houston, Texas. His previous stories for EWNS examined Mérida Spain’s Roman ruins and Captain James Cook’s exploration of Australia.