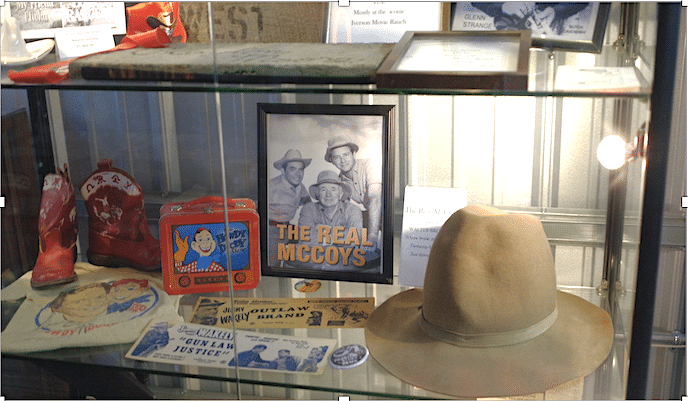

The Real McCoys TV series, which was set in the San Fernando Valley, aired on CBS between 1957 and 1963. Photo credit: Jian Huang

By Jian Huang

When visitors coming to Los Angeles try to imagine Hollywood, most think of award show celebrities, the Hollywood sign above Beachwood Canyon, massive tour buses slowly driving past million dollar homes of long-dead starlets or Marilyn Monroe impersonators along Hollywood Boulevard who will pose for a selfie for $10.

But “Hollywood” is much more than glitz and gossip. For starters, the real Hollywood is not located in “Hollywood” at all. The real Hollywood is actually about 10 miles north of the seedy Walk of Fame in the San Fernando Valley, where major film studios like Warner Bros, Disney, and Universal are located.

If a sightseeing bus tour or a visit to Madame Tussauds does not provide a sufficiently satisfying insight into Hollywood history, then Uber your way to the Valley Relics Museum at the Van Nuys Airport.

Down in the Valley

Located inside two hangars, the museum offers a one-of-a-kind collection of artifacts specific to the San Fernando Valley (also known as The Valley). It is a glimpse into the obscure history of Hollywood and the lives of those who worked in The Business and lived nearby.

Founded by valley native Tommy Gelinas, the eight-year-old museum started initially as a personal collection of rescued neon signs from local businesses that went bust. Eventually, Gelinas brought in Hollywood historian Julie Ream to co-curate and expand the Hollywood section of the museum. She brought in her personal collection, as well as those in her network of famous friends. As they say, “In Hollywood, it’s all about who you know.”

Pee Wee Herman’s famous bowtie suit was worn by James Brolin in Pee Wee’s Big Adventure from 1985. Photo credit: Jian Huang

Today, the gallery space is lined with display cases full of photographs, postcards, colorized advertisements, yearbooks, negatives, clothing, books, jewelry, and novelty items like matchbooks and menus. Visitors will recognize iconic memorabilia like Pee Wee Herman’s bow-tie suit and the bottle from the television show I Dream Of Genie (1963).

“The Valley is a suburb of Hollywood,” explains Ream. “People who worked in Hollywood raised their families in the Valley.” Born in nearby Glendale, Ream has a deep history with Hollywood coming from a family of actors.

Rooted in farming and ranching, today’s San Fernando Valley sprawls across 260-square miles of Los Angeles County. The region covers four independent cities, two unincorporated communities, and 33 distinct neighborhoods within the City of Los Angeles.

Tom Mix, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers

In 1934, studios implemented the “thirty-mile-rule” or “studio zone” for its workers to help reduce labor costs. As a result, much of the abundant farmland in the San Fernando Valley was turned into movie ranches. Visitors may recognize studios like Big Sky Movie Ranch, RKO Ranch, Paramount Ranch, Iverson Movie Ranch, and the infamous Spahn Movie Ranch, which was depicted in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood (2019).

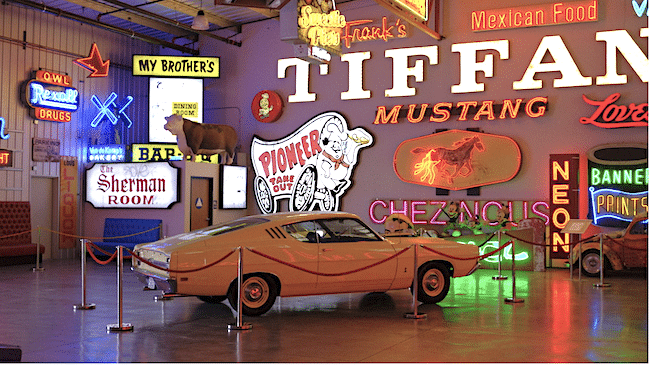

Signs from The Tonight Show with Jay Leno to one of Bob’s Big Boy famous figures holding a giant hamburger adorn the tightly packed wall space of the main hangar. Gelinas’ personal collection of BMX bicycles hangs from the ceiling, memories of a Valley childhood from the 1980s and 90s.

“Living in the Valley, I remember these things,” says visitor Linda Kline. “I love the neon and I miss the old diners, so it’s cool to see that kind of thing.”

Car aficionados will recognize several classic automobiles parked in and around the museum. A Volkswagen bus from Fast Times At Richmont High (1982) is part of the collection, as well as cowboy designer Nudie Cohn’s 1975 Cadillac Eldorado.

For those familiar with industrialist Howard Hughes, who once owned RKO Pictures, or have seen Leonardo Di Caprio in The Aviator (2004), there is a display with photographs and model airplanes from the Valley’s once-booming aerospace industry. After World War II, between 60 to 70% of the American aerospace industry, like Raytheon and Boeing, were located in Southern California. Ream’s husband Bob, a retired pilot and Lockheed Martin employee of 45 years, curates the aerospace exhibit.

From Cowboys to Aerospace

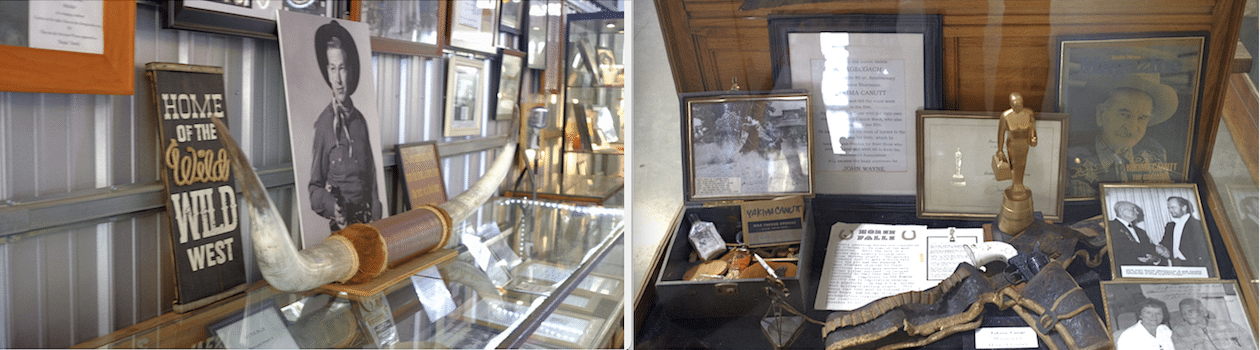

The museum also houses an impressive collection of costumes, and photographs from Westerns like Stagecoach (1939), The Real McCoys (1957-1963), Bonanza (1959-1973), and Gunsmoke (1955-1975). These iconic shows played a crucial role in keeping Hollywood alive during the decades that followed The Great Depression.

Good weather and plenty of space made the San Fernando Valley an ideal place for movie studios to crank out inexpensive Westerns. Photo credit: Jian Huang

In a time of unemployment and financial hardship, Hollywood prospered by offering Americans what they desperately wanted: inspiration at an affordable price. Stories of the lone hero tapped into an American ethos of the time with pioneering protagonists like John Wayne and Gary Cooper.

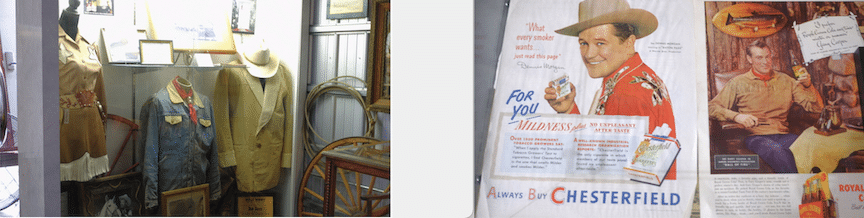

B-Westerns in the 1930s became especially popular because they were inexpensive to make and quick to crank out. Whereas a major Hollywood studio film cost between $100,000 to $1,000,000 at the time, B-Westerns were made for as little as $3,000. Known as Poverty Row studios, the 1930s saw the birth of budget studios like Mascot Pictures, Tiffany Pictures, and Columbia Pictures. Most cranked out profitable B movies exclusively. Corporations also cashed in on this popularized aesthetic with advertisements from cola to cigarettes.

The Western genre saw its rise to fame in the 1930s Depression era. Cheap to make and fast to crank out, this genre became so popular that even big corporations wanted in on the action. Photo credit: Jian Huang

The real star attraction of the museum, however, lies in the adjoining hangar. Frequently rented out as an event space, the second hangar dazzles with multi-colored neon signs from businesses of the Valley’s past. The iconic signs include Mel’s Drive In where George Lucas filmed American Graffiti (1973), and The Palomino Club that made an appearance in Any Which Way But Loose (1978) starring Clint Eastwood.

Before founding the museum, Tommy Gelinas, made a career for himself turning defunct signage into a successful t-shirt business. Visitors who want to take home a piece of the Valley can choose from several options in the museum’s gift shop from Pioneer Chicken to Tempo Records.

The most popular section of the museum is probably the Family Fun Arcade. Visitors are welcomed to play more than a dozen gaming machines for free along the event space wall. There are several pinball machines, as well as games like Neo Geo, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Grand Theft Auto, and even Pac Man.

“It’s like going to a family reunion,” says Ream. “There’s something here for everyone.”

The real star of the museum is its collection of restored neon signs from old San Fernando Valley businesses. Photo credit: Jian Huang

Though there are thousands of items exhibited, only a small portion of the collection is actually on display. Though relatively young for a museum, its reputation for collecting all things Valley is quickly growing. Donations come in all the time and for Ream, curating which objects to show is often the biggest challenge. “There’s not enough room for everything!”

Visual Historiography

A book on the museum is currently in the works that will document the history of its collection and the San Fernando Valley, publication date to be announced sometime in 2022.

The Valley Relics Museum is open most Saturdays and Sundays, from 11 am to 4 pm. General admission is $15 and children under the age of 10 can enter for free. Readers of East-West News Service are welcome to call Ream at (661) 478-1101 ahead of their visit to arrange a docent tour with paid admission.![]()

Jian Huang is an arts & culture writer and winner of the PEN America Emerging Voice award. She has written for several publications including LA Weekly, LitHub, and the Los Angeles Public Library’s ALOUD series.