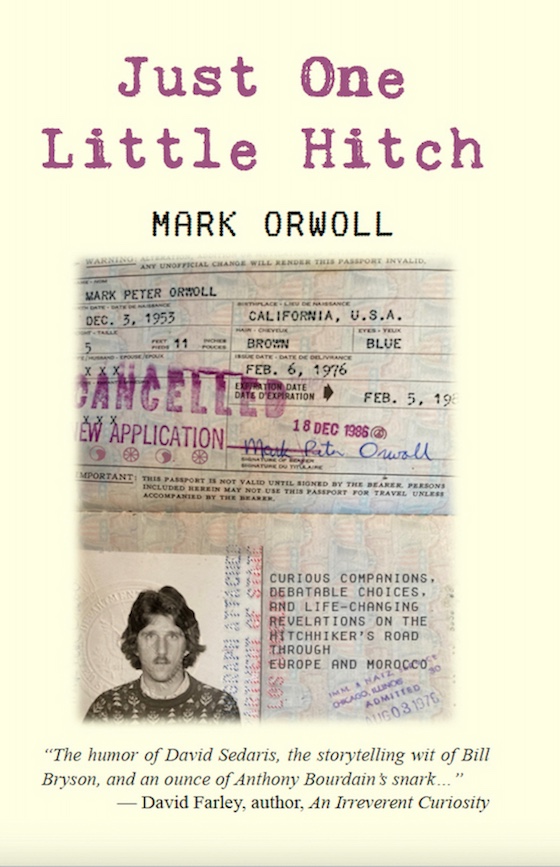

Curious Companions, Debatable Choices and Life-Changing Revelations on the Hitchhikers’ Road Through Europe and Morocco

What was it like to be young, carefree, and on the road a half-century ago? A new book excerpted below by author Mark Orwoll explains how hitchhiking, hippies and hostels all came together – temporarily – for a 1970s college dropout who decided to thumb his way through Europe and Morocco.

European Dreams, La Mirada, California, February 1976

In my mind, Europe was a mixture of Brothers Grimm cottages, imposing stone castles, Sherlock Holmes, American expatriates at Paris cafés, hot chocolate on the snowy decks of Swiss ski chalets, and, possibly, bosomy Bavarian barmaids proffering liters of strong Swabian beer on a silver tray. It’s a pretty picture. And yes, feel free to write in the margins, “What an idiot” as you see fit. I probably would if I were you.

The author and girlfriend, Marin County California, circa 1974. Collection of Mark Orwoll.jpg

At last, only weeks before leaving, I buckled down. I boned up on my Baedeker, prepped my clothing and gear, and made potential itineraries with enough latitude for kismet to sprinkle stardust in my path and guide me where it might.

Nothing left to do now but go.

Skirting Serious Crime: Frankfurt, Germany, March 1976

Germany was a country that had been defeated in a world war just thirty years earlier, then carved into East and West, one Communist, one democratic. Unemployment and inflation were ravaging the economy in the mid-Seventies. The Baader-Meinhof Gang, a terrorist group, blithely assassinated, kidnapped, bombed, and possibly shoplifted their way from Cologne to Munich in their fight against “global capitalism.” To top it off, Frankfurt was the gangster capital of Western Europe.

The Germans had bigger fish to fry than the egregious width of my blazing-white tie.

An Unplanned Museum: Trier, Germany, March 1976

When the Romans invaded in 15 b.c. the Germans considered them uncouth arrivistes. Trier had already been inhabited for thirteen hundred years.

That didn’t stop the conquerors from making the city their own. They built a twenty-five-thousand-seat amphitheater, a four-mile-long city wall, temples, baths, palaces, massive city gates, and other evidence of hard-charging, in-your-face cultural imperialism. Emperor Constantine authorized the building of a cathedral, now the oldest Christian church in Germany, in 326.

All that Roman activity set a precedent. Everyone in charge of Trier from then on felt compelled to leave something behind as an architectural legacy, if only to save face, resulting in grand market squares, statues, imposing civic structures, monasteries, and medieval mansions. Trier, Germany’s oldest city, became an outdoor archaeological museum.

Trier is among the oldest and most architecturally distinguished cities in Europe. Photo by Carlos Teixidor Cadenas

A Beautiful Park: Paris, France, April 1976

Over to the Quai du Louvre I went from where I could see that most charming of small Parisian parks, the Square du Vert-Galant, sitting prow-like at the western end of the Île de la Cité.

I crossed the Pont Neuf and skipped down a flight of stairs to the edge of the park. Lovers dangled their legs over the embankment and listened to a busker strumming a guitar and singing something romantic in French. Elderly people, standing, hands held behind their backs, still dressed for winter, gazed serenely at the river.

The setting sun was now deep orange with a square of bright, bright yellow near the top, leaving a reflection on the water that passed below seven bridges before ending at my poor pair of blue canvas sneakers. The green and spreading chestnut trees sent out clean, rich aromas. Had it been a scene from a 1930s Merrie Melodies cartoon, the flowers would have begun to sing falsetto and dance. I thought I would explode with wonder.

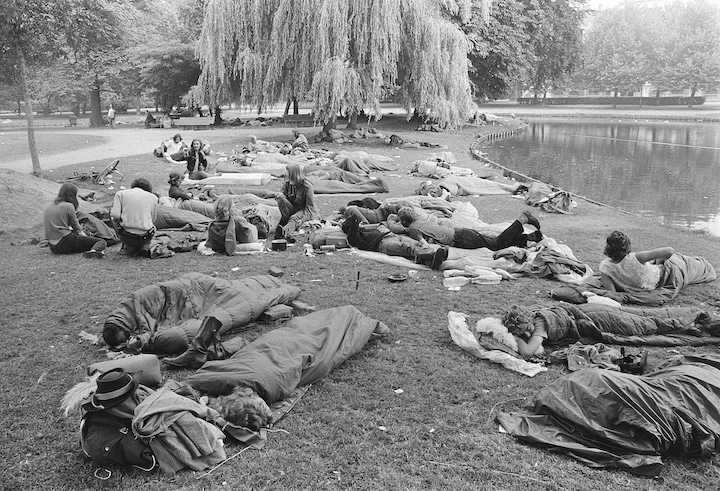

Hippies from across Europe and America would crash in Amsterdam’s Vondel Park to save the $2 cost of a youth-hostel bunk. Courtesy of Dutch National Archives.jpg

A Magical Depot: Paris, France, April 1976

A time once existed, back in the mists of history, when unironic architects designed Temples to Transportation.

The Gare de Lyon was such a place. With its classical façade, enormous clock tower, and the vast plaza out front that allowed you to stand back and soak in the building’s beauty and an almost overwhelming amount of sculptural decoration, the terminal was as ornate as a Dauphin’s chateau. The massive, warehouse-like main hall was bright, thanks to skylights and second-floor windows running the building’s full length. People crossed the interior in every possible direction. I wouldn’t have been surprised to discover some of them were walking in circles if only to linger without loitering.

The clock in the tower chimed ten.

May Day Danger: Barcelona, Spain, May 1976

I sensed trouble afoot after just fifteen minutes of walking around.

Two men picked up a park bench that had not been bolted down, carried it across the street, heaved it through a shop window for no reason that I could fathom, and then jogged away. Not five minutes later, forty or fifty people ran in my direction from farther down the Rambla. When they got to where I sat watching them, they seemed terrified of something. I stood and walked away from whatever might be behind them. Other people, seeing the scared runners, either fled with them or stood motionless against the buildings on either side of the avenue, as if imitating statues would camouflage them from the unseen danger.

A Guardia Civil jeep stopped next to the smashed window. Two uniformed men stepped out and were soon joined by other policemen on foot. An officer spoke to the men, who pulled out their billy clubs and ran as a group down one of the side streets, ready to crack some skulls and kick some butt. Farther down the Rambla I could hear the sound of more glass breaking, shouts, and sirens.

Welcome to Barcelona!

I returned to my hotel and locked the door.

Camel Poop: Fnideq, Morocco, May 1976

We pulled over and persuaded the old man, in exchange for some wadded-up Spanish pesetas, to let us take turns sitting on the camel for photos. He had us remove our shoes—I assumed to avoid hurting the hideous, slobbering brute—commanded the drooling devil to kneel, then demonstrated how to wrap our legs tight against the camel’s rear haunches, lean forward, and hold onto the hump.

How hard could it be to ride a camel?

The butt-ugly ungulate sensed my mastery of the situation. I climbed into position, expertly clamped my legs as instructed, and grabbed a couple of handfuls of camel fur, which was about as pleasant as clutching your father’s weekend whiskers. The spittle-stained Satan of the Sahara turned its head 180 degrees to stare at me with its malevolent, cow-like eyes. With a shout from the camel driver, the varmint rose from its crouch, quicker than I’d expected, and immediately, petulantly, squatted back on its belly.

As if in a bizarre gymnastics event, I rolled backward and did a neat little flip off the camel’s ass. With an oomph! they could have heard at Rick’s Café Americain 250 miles away, and with such precision you’d have thought I was aiming for it, I landed in a pile of camel crap.

Instead of riding the Ship of the Desert, I’d tumbled into the shit of the desert.

‘Mula, Mula, Mula!’: Cordoba, Spain, May 1976

A skinny teenage boy stopped his farm wagon at the roadside when he saw me. His cart, pulled by a mule, carried a half-dozen bales of hay. The wagon wheels were painted bright red, and I saw smears of red paint on the boy’s trousers. A friendly dog was with the boy, walking beside the wagon. The dog hopped confidently over to me and sniffed my ankles curiously.

“No hay mucho tráfico aquí,” the boy said. “¿Adónde va?” There isn’t much traffic here. Where are you going?

When I told him I was on my way to Córdoba, he indicated I should climb aboard, that he would take me to a better place for hitchhiking. “Cinco kilometros, más or menos.” Five kilometers, more or less.

The problem, for me, was that the wagon had no seat. The boy had been standing on one of two poles that extended in front of the wagon and attached to the mule’s harness. I removed my pack and tossed it into the back with the hay, then hopped onto the opposing pole, grasping the edge of the wagon box with both hands. I worried whether the additional weight might be too much for the lone mule, but the road ahead of us was flat and smooth, and the boy himself showed no concern.

The only time I almost fell off my narrow balance beam was when the mule first began to walk, starting with a jerk, but I quickly got my sea legs and even began holding onto the wagon bed with one hand only, as the boy was doing. The boy, of course, had no choice, because in his free hand he held the reins.

A drainage ditch paralleled the side of the road. The dog walked between the cart and the ditch and barked in warning whenever the mule seemed to veer too close to the trench. Some dog.

“Mula, mula, mula!” the boy shouted in encouragement, shaking the reins.

We went on that way for several miles. The boy was bringing the hay to his father’s ranch, he said, which was not far. As we bounced pleasantly along, he began to sing quietly, an unexpectedly somber melody whose words I couldn’t make out. Again, the dog barked a warning, and again the boy shook the reins and called out, “Mula, mula, mula!”

Beware the Moors: Chagford, England, June 1976

At the eight-hundred-year-old Three Crowns Inn in Chagford, where I stopped for a lager after Jack and Jackie dropped me off, I told the young man behind the bar that I planned to hike on Dartmoor the next day. His reaction was to give me a look that I might have expected from a Carpathian shepherd on hearing I was en route to Dracula’s Castle.

“Cor, that’s no place for a walk unless you’re prepared,” he said in a voice like Long John Silver’s, setting the pint glass in front of me. I half-expected him to make the sign of the cross and hang more garlic over the doorways. “You’ve got your ordnance survey, I suppose. You’ve told your friends your route and what time you expect to arrive, I suppose. You’ve got Wellies and a mac, I suppose.”

I don’t suppose I knew what an ordnance survey was. I definitely didn’t know what Wellies were. As for macs, I knew only that bankers didn’t wear them in the pouring rain. I had no friends to whom I could tell my route and arrival time. I wasn’t even sure of that myself.

“Oh yeah,” I replied. “That’s all sorted.”

As he wiped the counter, he surreptitiously looked at my pitiful yellow backpack, stitched together as crudely as Frankenstein’s Monster, and pursed his lips.

“People get lost out there all the time,” he warned. “They get off on the wrong footpath and then you’re readin’ about them in the Western Morning News.”

Stonehenge Free Festival: Salisbury Plain, England, June 1976

Hippies were everywhere.

Small groups of them were coming up the A303 from the west, others from the east. I saw hippies cresting a rise to the north. In the distance, hippies were climbing over the stones of the monument. They were setting up tents and tepees and makeshift shelters that resembled the sort of lean-tos a desperate mountaineer might construct at the last minute in bad weather.

Scattered about the field one could find hogans, hovels, wickiups, and homemade sunshades. Pennants, flags, and brightly colored strips of cloth flapped and snapped from tree-branch poles next to the rude lodgings. The growing colony on the grassland looked like a cross between a medieval fair and an Arapaho village.

And the cars! The vehicles filling up the grounds marked the strangest, motliest collection of transports I’d ever seen. Morris Minors with peace symbols on the doors. VW Beetles in psychedelic colors. More transit vans like the one that had picked us up. Renault Dauphins. Deux Chevaux. Motorcycles with sidecars. We even saw several gypsy wagons that, for all I knew, could have been pulled there by donkeys.

Some of the campers had already set up tape decks and speakers. Rock music blasted from the main camping area, just a few hundred yards from Stonehenge itself (or “the stones,” as everyone called the monument).

In the 1970s, Amsterdam was Hippie Central, and the coolest part of town was Dam Square. Courtesy of Dutch National Archives.jpg

Cough Shops: Amsterdam, July 1976

While making my dinner in the communal kitchen, I met two Canadian young men who said they knew a coffee shop where we could buy hash. A coffee shop, in Amsterdam and elsewhere in the Netherlands, usually referred to a café that openly sold weed and hash, which, while not legal, were tolerated by the authorities. Because people often smoked their purchases right there, the wags called these establishments “cough shops.”

In the coffee house, customers were drinking tea and coffee from the coffee bar, but they were also toking up right at their tables. In the back of the shop, a super-hippie with hair down to the middle of his back, beads and bracelets everywhere, and a serious expression stood at a counter with a bright overhead light. Three or four people had formed a line on the opposite side of the counter, and each in turn spoke softly to the dealer, who would then weigh some dope on a scale and take the customers’ money.

I bought three grams of dark green Moroccan hash, which looked remarkably similar to the camel poop I’d fallen into on the road to Volubilis.

Most Charming Village in Germany: Rothenburg ob der Tauber, July 1976

Rothenburg ob der Tauber is one of the most photogenic small towns in Germany. Photo by Berthold Werner

Rothenburg ob der Tauber could be the most charming, intact, medieval walled city in all of Europe. One can circle the entire town by walking along its crenelated battlements. The block-paved streets swirled and curved and sloped, passed under five-hundred-year-old archways, and intersected at unexpected angles. The homes and the shops slanted to various degrees, their high-pitched roofs stippled with tiny windows and their window boxes bright with flowers. The people of Rothenburg ob der Tauber were perfectly aware of just how agreeable and good-looking their small city was.

Dinkelsbühl, to the south, where I stopped briefly the next day, could hardly compare with Rothenburg. It had an abundance of gaily painted medieval houses, handsome towers, and gatehouses in the city walls, but its streets seemed too wide, its churches too cold and off-putting, and its emotional vibe lacked the joy that seemed to imbue its northern neighbor.

No matter. I hadn’t planned to stay overnight in Dinkelsbühl. I was heading to another classic walled city, Heidelberg. Getting there, though, had proved to be a problem. Rain had been coming down since I left Rothenburg. Few people wanted to pick up a sopping-wet hitchhiker.

The Spookiest Hostel: North Wales, July 1976

Ty’n Dwr Hall, the local hostel, was a falling-down wreck of a once grand mock Elizabethan manor house from the reign of Victoria. Inside, it fulfilled every notion of a haunted mansion or the scene of an Agatha Christie murder mystery.

If there had been other travelers, it might have been amusing to explore the old pile, but the place was too large and spooky to investigate on my own. The nonresident warden left for the night at seven, and I was the only living person in the manor house.

The wide oak staircase creaked like someone moaning. A large dining room echoed even when no one spoke and had atmospheric cobwebs hanging from its dusty glass chandelier. Eerie passageways went either to nowhere or to somewhere I probably didn’t want to go, at least not by myself. A noisy lightning-and-thunder storm raged through the night. Because of the horrible weather, I couldn’t even walk into town, so I stayed in my bunk, reading and trying not to notice any wandering wraiths.

Home Again: Los Angeles International Airport, August 1976

As I waited for my backpack at the conveyor belt, my Dad nodded at some people standing directly opposite, also waiting for their luggage. Frank Zappa, looking bored and smoking a cigarette, waited for his bags along with the rest of his iconoclastic rock band. They had been on my flight home, and I hadn’t realized it.

I was back in Los Angeles, California, USA!

When we arrived in La Mirada, I said goodbye to my Dad and promised I’d come to see him in Downey in the next day or two. Then I went inside and saw my Mom. She was stunningly beautiful, movie star beautiful, and always had been, but never more so than at that moment. She grasped me around the shoulders, pulled me close, and squeezed until it almost hurt. She poured me a cup of coffee. Even though the foul-smelling brew was Folgers Instant, it may well have been the single best cup of coffee I’d have ever had, to this day. It’s certainly the one I remember more than any other.

I was home at last. I sat back on the living room sofa and closed my eyes. But I didn’t have too much time to waste.

I had a career to begin.![]()

The author today, with a Peruvian shaman. Collection of Mark Orwoll

Mark Orwoll, who writes frequently for East-West News Service, attributes his 45-year career in journalism to the hitchhiking trip he took through Europe and Morocco in 1976.