Most of Hinohara is in the beautiful Chichibu-Tama Kai National Park. Photo by Beth Reiber

By Beth Reiber

I went to Japan some 40 years ago to write travel articles but ended up staying a couple of years, first as editor of a travel magazine published in Tokyo and then to write the first of several guidebooks on Japan. My Frommer’s Japan guidebook alone ran more than 600 pages and covered about 65 destinations, all of which I visited more than a dozen times over several decades for updated editions. Add the other villages, hot-spring resorts, islands, and places I’ve visited over the years, and I think I can rightly call myself an expert on Japan.

Writing about Japan for so many years also allowed me to witness change, including the migration of young people from rural Japan to the cities for employment and the gradual climb from a dearth of international visitors to over-tourism in some places. My interest now lies in exploring overlooked communities, mostly rural, that want tourists and offer something unique.

That’s how I came to the mountain village of Hinohara, located on the outskirts of Tokyo, where cypress and cedar have been the mainstay of the local economy since the Edo Period (1603–1868). As young people moved to the city or had fewer children, Hinohara lost population, down from 6,000 inhabitants in 1960 to fewer than 2,000 residents today. Salvation might just lie in those ancient trees, continually replanted by past generations so that their progeny might reap the rewards.

Today those benefits include grassroots initiatives such as guided hikes to connect city folk to nature and cypress products like essential oils and the world’s first cypress-distilled liquor. These initiatives are based mostly on the concept of shinrin-yoku (“forest bathing”), scientifically proven to reduce stress, increase energy, and boost mood due to chemicals called phytoncides. Turns out, evergreens are the largest producers of phytoncides.

Tokyo And Kyoto: Japan’s Most-Visited Cities

Since the pandemic, Japan has become a tourism hotspot, fueled in part by a weak Japanese yen that makes foreign currencies go further. During the first three months of 2024 alone, Japan received 8.5 million international travelers, about the same number it received in all of 2010 and putting it on track to exceed 2023’s 25 million visitors.

Tokyo’s Skytree towers over the rest of Japan’s capital. Photo by Beth Reiber

Because many are first-time visitors, Tokyo and Kyoto are on their bucket lists. Why not? Tokyo is so wired and electric you can feel it in the air. There is a thrill of excitement, the anticipation of discoveries both weird and wonderful, whether it’s a neighborhood shrine or Godzilla’s head peering above buildings in the nightlife district of Shinjuku. It is surreal to see the sprawling metropolis from Tokyo Skytree, the world’s tallest free-standing broadcast tower, but the world’s most extensive collection of Japanese art and antiques at the Tokyo National Museum is reason enough to visit the Japanese capital.

Kyoto is Japan’s most beautiful city, sometimes achingly so: the shape of a willow tree as it arches over a narrow canal; a glimpse of the white-dusted neck of a geisha apprentice as she disappears around a corner, her hair coifed perfectly above. There are gardens shaped to perfection like heaven on earth, most attached to Kyoto’s 2,000 temples and shrines that might have histories stretching more than a thousand years.

But like Venice, Paris, and other popular destinations, Tokyo and Kyoto have an overabundance of visitors. Kyoto is especially hard hit, with buses so crowded that authorities recently launched express shuttles that take tourists directly to major attractions and keep them off local conveyances. Kyoto’s Gion geisha district once had few outsiders, but snap-happy crowds chasing after geisha and their apprentices have become so overwhelming that access is now restricted in some areas.

The approach to Kyoto’s Kiyomizu Temple is crowded year-round. Photo by Beth Reiber

Even Mount Fuji is suffering from a stampede of hikers, causing authorities to cap visitors at 4,000 a day and charging a climbing fee. Officials in one town near Mt. Fuji became so exasperated with foreign tourists taking photographs of a convenience store with Japan’s most famous mountain rising behind it, ignoring parking restrictions and leaving behind litter, they recently erected a massive barrier to block the view.

Beyond Tokyo And Kyoto

But just as New York and San Francisco can’t define the United States, there is more to Japan than Tokyo and Kyoto. One of the most striking characteristics of Japan is that it stretches about 1,800 miles in an arc from Okinawa in the southwest to Hokkaido in the northeast, with varied topography, climates, and even cultures.

Most visitors stick to the main island of Honshu, home to major cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and Nagoya, but the island’s northern Tohoku region doesn’t get near the international recognition it deserves. It begins about 150 miles north of Tokyo, spans six prefectures and offers remote hot-spring spas, rugged wilderness and many historic sites.

Hokkaido, Japan’s second-largest island, accounts for 22% of the nation’s landmass. It has six national parks but just 4.2% of the country’s population. Then there’s Okinawa, which wasn’t even officially part of Japan until 1879 and has a distinct culture, not to mention killer beaches and scuba diving.

What Guidebooks And Social Media Have Wrought

It’s no secret that instant news and social media have vastly changed the world of travel. That agonizing decision to thwart crowds by obliterating views of Mt. Fuji? The whole debacle erupted after a foreign social media influencer posted a photo in 2022 of the convenience store, with Mt. Fuji seemingly perched on top.

The Frommer’s guides to Tokyo and Japan have necessarily funneled travelers to the same places. In the 1980s I recommended Tokyo’s former Tsukiji fish market for its tuna auctions. Crowds inundated the market, eventually forcing authorities to impose a lottery, and, in the end, close the market to visitors altogether It has since moved to a new location that separates visitors behind glass.

Crowds also have changed Ogimachi, formerly a delightful hamlet of 600 residents living in thatched-roof farmhouses beside the Shokawa River in the Japan Alps on Honshu. In the 1980s, day-tripping Japanese were the only visitors. Since being declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995, the transformation has been dramatic. On the eve of the pandemic, Ogimachi was a sea of jostling tour groups being led by guides with yellow flags and bullhorns.

Ogimachi in the Japan Alps now has visitors even in winter. Photo by Beth Reiber

A Mountain Town Reinvents Itself By Returning To Its Roots

Which is why I appreciate Hinohara. Ask Tokyoites and most probably have never heard of it. It doesn’t have a famous shrine or a natural wonder that draws tourists. It’s not so much what you’ll see as what you won’t. No noisy tour groups. Not many visitors.

Hinohara is Tokyo Prefecture’s sole mainland village (the other villages are on remote islands), less than two hours from downtown Tokyo. With little flat land, the mountain town is strung along a valley following the contours carved by the Akigawa River that is fed by countless mountain streams. Its star attractions are its waterfalls, but its twisting roads also attract cyclists and motorcyclists. As much as 75% of Japan is mountainous, and this town is hemmed in by steeply wooded hills. In fact, 93% of Hinohara is covered by forests and 80% lies in Chichibu-Tama-Kai National Park.

Here guided walks on secluded forest paths introduce visitors to trees, bushes, medicinal herbs and the phenomenon of forest bathing. Hinohara’s long history with trees has morphed into something that might save it. It isn’t the only place in Tokyo Prefecture where you can hike, forest bathe, and get away from it all. But it is one of the least visited, in contrast to Mt. Takao, a popular and therefore often crowded hiking destination an hour away from Tokyo.

A Walk In The Woods

There’s a Japanese word for it: komorebi, the play of dappled sunlight filtering through leaves. Komorebi’s presence all around me is just one of the things my guide, Kazuhiro Kobayashi, asks me to notice.

“The important thing is to feel the five senses,” Kobayashi says, “so be sure to take deep breaths.”

We’re in Hinohara’s Tomin no Mori (Forest of Tokyo Citizen), which is located halfway up Mt. Mito in Chichibu-Tama Kai National Park. It’s autumn and brilliant colors of red, yellow and orange are interspersed among the evergreens. There are many long and beautiful hikes. One is a 4.7-mile trek that climbs 1,640 feet to the top of Mt. Mito, once a center of ascetic mountain worship that sometimes offers views of the elusive Mt. Fuji. But we are taking the gentle, one-hour Mito Otaki Falls route, named in 2007 as a Forest Therapy Road.

Observing komorebi, our attention turns to sounds–rushing streams, wind in the trees, and leaves crunching underfoot–and smells of a forest. Kazuhiro gives me a leaf from the Japanese katsura tree, which emits a sweet caramel smell but only in autumn after the color change. Kuromoji (spice bush), used for making toothpicks as well as essential oils, has a smell that changes with the location of the tree.

But evergreens are the stars of the show. Most of the evergreens in Tomin no Mori are sugi (Japanese red cedar), native to Japan and the country’s national tree. Sugi is often planted around Shinto shrines, reflective of this indigenous religion’s deep-seated connection to forests in ancient times. With its straight grain, durability and natural resistance to decay, insects, and fungi, cedar has long been used for building temples, shrines and traditional Japanese homes.

But Hinoki (Cypress) is King

“Hinoki” was one of the first Japanese words I learned, because any inn that had a traditional wooden bathtub always proudly points it out. Like sugi, hinoki is revered for its beautiful and durable wood resistant to splitting, warping and rot. It feels good to the touch and grows stronger as it ages, making it valuable construction material for buildings, tools, machinery, civil engineering, and ships. Well-built structures made with hinoki can last 1,000 years or more, with the prime example being Horyuji Temple in Nara, the oldest wooden structure in the world, built sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries.

Our short hike ends at Mito Otaki Falls, one of 50 waterfalls in Hinohara that are somewhat accessible and well-known to villagers who love waterfalls.

Dating from the 7th Century, Horyuji Temple, the world’s oldest wooden structure, is made of hinoki. Photo by Beth Reiber

Forest Bathing

“Walk slowly through the forest for forest therapy,” Kobayashi explains early on our walk. “It lowers the blood pressure and reduces stress. But the effect is that it helps you relax.”

When I first heard about “forest bathing,” I dismissed it, wondering why Japan would lay claim to something we all know intuitively: that being in nature is good for us. I was especially skeptical because forest bathing, or shinrin-yoku, was coined in the 1980s by the Japanese government. It seemed like public relations to me.

But research in the 1990s proved that shinrin-yoku provided not only emotional or spiritual benefits but also physiological ones. Even the U.S. Forest Service advises, “Exposure to forests strengthens our immune system, reduces blood pressure, increases energy, boosts our mood and helps us regain and maintain our focus in ways that treeless environments just don’t.”

That’s because plants produce chemicals called phytoncides, essential oils plants use to ward off insects, bacteria and fungi. The article on the U.S. Forest Service website went on to say that phytoncides improve our immune system by increasing natural killer cell activity that responds to virus-infected cells and tumor formation. Phytoncides also increase anti-cancer proteins and reduce heart rate, stress hormones, anxiety, depression, anger, fatigue and confusion. Not only that, but the increased natural cell activity can last for more than 30 days after a forest visit.

Evergreen forests are the largest producers of phytoncides. They come floating down as you walk under them, making me think it isn’t forest bathing as much as forest showering.

“The smell of the forest is very important for human beings,” Kobayashi says.

All I know is that being in the woods makes me happy.

Mito Otaki Falls in the Forest of Tokyo Citizen is one of 50 waterfalls in Hinohara. Mito Otaki is especially beloved by Hinohara residents. Photo by Beth Reiber

More Immersion In Hinohara’s Forests

My education in Hinohara’s forests continues at the Tanaka Forest Company, the corporate name of a family engaged in forestry since the Edo Period. After Chiyoko Tanaka married a 15th-generation Tanaka forester, she immersed herself in plants, including plant-based products and guided medicinal tours. At her disposal are the Tanaka family’s 500 hectares of mountain forests behind her home.

Participants learn how to make teas or medicated baths using wild grass, mugwort and kuromoji. Tanaka says kuromoji–the toothpick wood–grows naturally near water under cypress and cedar trees and is considered to have analgesic, sedative, and anti-inflammatory properties, as well as calming the mind and supporting sleep. Added to baths, it’s said to be good for neuralgia, rheumatism and joint pain, while mugwort reportedly helps reduce colds, lower back pain and rough skin.

Tanaka also offers seven guest rooms in a house built by her father-in-law from fallen trees in their forest. It’s mindboggling to contemplate what it must take to cut and remove trees on such dense, steep hills inaccessible to machinery.

“Trees are always being replanted because it takes about 70 years for a tree to grow,” Tanaka says, “so we’re doing it for progeny. Because we know the age of the tree, we know who planted it. Trees harvested now were planted by the grandfather.”

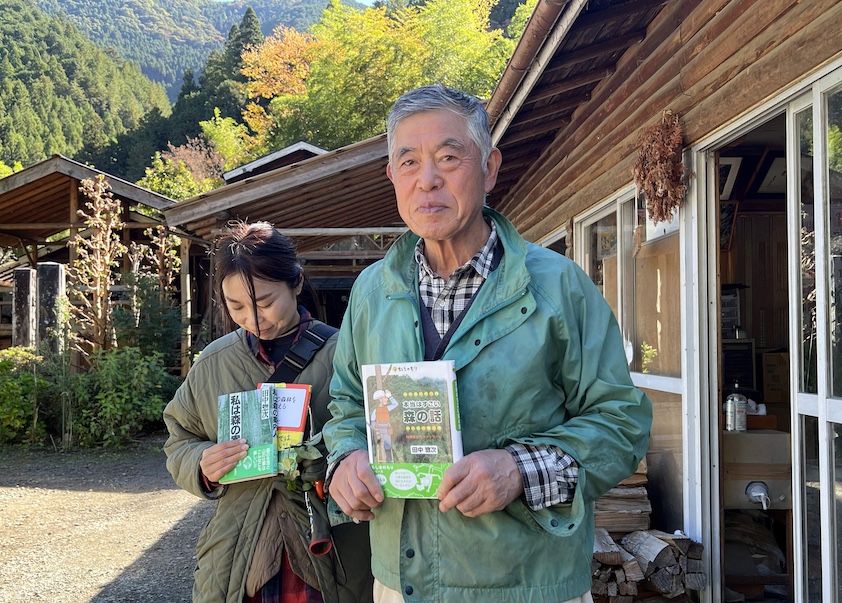

Soji Tanaka and his daughter-in-law, Chiyoko, with books Tanaka wrote for children during the 54 years he worked in Hinohara’s forests. Photo by Beth Reiber

My favorite walk in Hinohara is to Hossawa Falls near the center of town. In keeping with Japan’s penchant for naming the best of everything, Hossowa is rated one of Japan’s Top 100 Waterfalls. But it’s not the waterfall itself that captivates me, but rather the 15-minute walk to get there. Passing a quirky café and a former post office now operating as a souvenir shop, I follow a stream as it winds past moss-covered boulders. Komorebi streaking through the trees gives the woods a mysterious, primeval atmosphere. It’s not surprising there’s a legend about a serpent that lives here.

Kabutoya Ryokan

Kabutoya Ryokan’s thatched roof is said to resemble a warrior’s helmet. Hinoki groves and soothing waterfalls are visible through the windows of their guest rooms. Photo by Beth Reiber

Other things to see in Hinohara include the village’s public hot-spring baths and a toy museum made, naturally, of wood. As for places to spend the night, Kabutoya Ryokan is a Japanese inn with a 400-year history. The inn’s name stems from the shape of its thatched roof, said to resemble a warrior’s helmet (kabuto), but equally fascinating is what was once a family mainstay under that thatched roof—silkworms, raised until World War II.

Keiyu Okabe, the 19th-generation caretaker of his family home, takes mesmerizing drone videos of Hinohara’s natural wonders. He says that before the war, every home was thatched. Now only four remain.

Okabe serves dinner beside a traditional irori hearth sunk into the floor, a feast that includes local specialties like uncoiled fronds of boiled leafy ferns, noodles and tofu, as well as chicken, beef and vegetables cooked over glowing charcoal. An impaled river trout is placed to bake beside the hot coals. Dessert is potato ice cream, which, like most Japanese desserts, is not overly sweet and tastes more like ice cream than potatoes. Hinohara is so proud of the potatoes it has grown since the Edo Period, that its village mascot is a potato.

Sleep comes easily on a futon laid upon tatami, serenaded by one of Hinohara’s ubiquitous waterfalls and surrounded by a forest shedding phytoncides.

Hinoki Essential Oils And Distilled Liquor

Discarded hinoki leaves are collected by WOODBOX for the production of essential oils. Photo courtesy of WOODBOX INC.

One of Hinohara’s most successful hinoki-related stories is of WOODBOX, a company that began manufacturing its products in 2018 and now has six employees. Under the joint guidance of engineer Yuji Yamaguchi and distillation technology expert Mitsuyo Yoshida, WOODBOX produces hinoki essential oil, mist and air freshener, all derived from discarded boards, leaves and sawdust resulting from cypress trees felled for the lumber trade and produced using homemade steam distillers.

The essential oils can be added to bathwater or sprinkled onto shavings of hinoki to place beside your pillow, while mist can be sprayed in the air or applied to small pieces of cypress wood to be placed wherever you like.

“You can use the leaf or wood of hinoki because the scent is different, “Yoshida says of the company’s oils and mist. “With the leaf, you can sleep deeply. With the trunk, you can relax and activate the brain.”

After succeeding in essential oils, WOODBOX then turned its attention to producing shochu, a traditional Japanese distilled spirit, made uniquely from Hinohara’s famous potatoes and hinoki. With a slight bite and earthy smell when consumed straight, it becomes smoother on the rocks or mixed with water or soda.

WOODBOX sells its brand, “shin rin yoku from Hinohara,” at its Hinohara Factory store, with essential oils and mists also available on its website and at SF76 in San Francisco. Each product sold, with a portion of proceeds going toward forest regeneration, comes with a QR code that shows its place of origin and provides information on Hinohara.

With WOODBOX products, therefore, the scents of Hinohara’s forests can be recreated at home. Hinoki trunk, thought to be both calming and invigorating, is considered good for recharging energy and focusing attention. But it’s hinoki leaf which is recommended for rest, relaxation and a sense of peace.

Hinohara products include hinoki essential oils, potato cookies, and shochu made from local potatoes and hinoki. Photo by Beth Reiber

Back home I tucked a packet of cypress shavings sprinkled with leaf essential oil inside my pillowcase. The smell ignited my memory, launching me into Hinohara’s woods, reeling me in, and then launching me out again, until, finally, the scent let me be. Now it just gently takes me back to a happy place, the walk to Hossowa Falls. And just as Koboyashi suggested on my guided walk in the woods, Hinohara taught me the power of a forest’s smell.![]()

Beth Reiber, a freelance journalist based in Lawrence KS, is the author of eight guidebooks. Recently, EWNS published her exploration of the ancient Roman resort of Herculaneum. For links to more of her articles, go to bethreiber.com.