Dinner in the American Queen’s grand J.M. White Dining Room features flavourful dishes redolent of the Old South. While departing New Orleans, the food reflected Louisiana’s French and Creole cultures. Photo by Toby Saltzman.

By Toby Saltzman

What sounded like a pickup line turned out to be friendly banter from a local who enjoys meeting visitors in his quiet Mississippi River town. Seated on the step of a yellow clapboard house, smile lines wrinkling around blue eyes, he called out, “How y’all doin,’ lovely lady? Are ya off the paddle wheeler?”

“Yes, the American Queen,” I answered, ready to pass him by.

“Oh, the real steamboat,” he beamed. “Prettiest on the Old Muddy. Where ya headed?”

Before I knew it, we were engaged in conversation. He, Christian Morrison as curious about me as I about him.

Turns out, Morrison’s Louisiana heritage is as old as the town. His family migrated from New York to New Orleans in 1856 prior to the Civil War. He grew up on a plantation on the other side of the Mississippi River and eventually raised a family there. He bought this little house in St. Francisville so his kids could attend the local high school. Now they’ve grown and his plantation house feels too big, so he often stays here on riverboat days, keen to meet passengers off the boats.

Inspired by Morrison’s congeniality, I walked on thinking he reminded me of how, over a century ago, former riverboat pilot Mark Twain, in his memoir Life on the Mississippi, portrayed people in riverside towns waiting for steamboats to arrive bearing passengers with money to spend in local stores, restaurants and hotels. Describing the towns’ mood before the boats arrived, Twain wrote: “The day was glorious with expectancy; after they had transpired, the day was a dead and empty thing…the whole village felt this.”

Ol’ Man River Keeps Rolling Along

Of course, life in southern Mississippi River towns has changed since the 19th century. Towns like St. Francisville are far from “dead and empty.” But small communities still depend on Show Boats like the one portrayed in the 1936 Broadway musical of the same name, whose most famous song, Ol’ Man River, still captures the pain and promise of life on the Mississippi.

Soon after embarking on the American Queen for a Mississippi River voyage from New Orleans to Memphis, I realized the symbiotic relationship of this vessel – the world’s biggest steamboat – to locals living beside the river. Along the way, I came to appreciate the river’s power, its impact on the South’s history and the pride it engenders in the 32 U. S. states that comprise its watershed.

Saying Goodbye to the Big Easy

Excitement flew on the breeze as the American Queen revved up her engines at the Port of New Orleans, sending curls of steam skyward from towering smoke stacks as her giant red paddle wheel churned waves into foam. As the brass calliope pipes fringing the top deck began tooting Scott Joplin’s The Entertainer, passengers cheered, excited by the prospect of rolling upriver atop a white gingerbread palace.

Powering America’s Westward Expansion

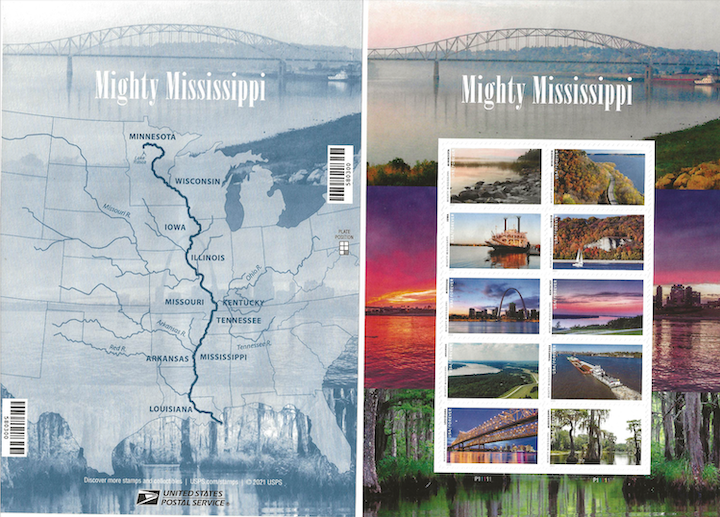

Evocative of historic steamships commemorated in 2023 stamps published by the U.S. Postal Service, the American Queen’s exterior mirrors vessels of the 1800s and early 1900s when steamships plied America’s rivers.

Steamships ultimately facilitated America’s westward expansion. Before steam power, boatmen navigating flat-bottomed keelboats depended on river currents and personal strength to pole boats upstream. When American engineer Robert Fulton launched his steamboat in 1807 to ferry passengers from New York City to Albany, he ultimately changed the course of river transportation.

U.S. Postal Service first class stamps commemorating the Mississippi River.

By then Thomas Jefferson had realized his dream for the westward expansion of America with the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Steamboats traveling the tributaries of the Mississippi River brought pioneers west, and many of them settled in riverside towns.

Steamboat Styling

Reminiscent of historic Victorian and Art Nouveau steamboats, American Queen’s interiors, renovated in 2012 at a cost of $6.5 million, feature wood-carved details and antique furnishings, notably in the Gentleman’s Card Room and Ladies’ Parlor. The long Mark Twain Gallery exudes an aura of intellectual worldliness befitting Samuel Langhorne Clemens, aka Mark Twain. Illuminated by brilliant Tiffany lamps, the gallery houses cabinets filled with first copies of Twain’s books plus memorabilia that includes early maps and navigation tools. I envisioned the author of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer seated in a wing chair, regaling rapt admirers with tales of his life as a river pilot, while mentally penning Life on the Mississippi.

Exploring my home for the next seven days, I realized the American Queen is a veritable museum of art. Its hallways are lined with paintings of Industrial Revolution-era ships. In the Chart Room on Deck 4 an antique wood steering wheel is engraved with Twain’s words: “Your true pilot cares nothing about anything on earth but the river, and his pride in his occupation surpasses the pride of kings.”

Women dressed as they would have been in 1859 before the start of the American Civil War guide visitors on tours of Nottoway, the South’s largest remaining antebellum mansion. Authentically furnished with antique furniture of the era, Nottoway reflects the opulent lifestyles of the era’s cotton barons. Photo by Toby Saltzman

Too Beautiful to Burn

The flush of dawn cast gleaming light on Nottaway, the South’s largest remaining antebellum mansion. Called the “White Palace,” the three-story, 53,000 sq. ft. Greek-Italianate mansion was built in 1859 by sugar magnate John Hampden Randolph for his wife and 11 children. Thousands of elegant plantation homes were torched during the Civil War, but Nottoway’s size and beauty appealed to Federal troops who made the home their headquarters. Immaculately restored in 2008, the antique-filled mansion is the heart of Nottaway Resort, a popular stop-over between New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

Show the Princess Some Respect

That afternoon American Queen passengers broke ranks to participate in various tours. Some explored the bayou on a boat ride through Manchac Swamp, a beautiful wetland filled with alligators. Supposedly, the swamp is haunted by a voodoo priestess who cursed the area a century ago after complaining of insufficient respect. Two villages that scoffed at her pomposity subsequently were destroyed by a hurricane. My tour followed a stretch of the Great River Road National Scenic Byway, which follows the Mississippi River for 3,000 miles through 10 states, from Louisiana to Minnesota.

Adjacent to Houmas House, the Great River Road Museum is filled with maps, historic artifacts and interactive displays that detail the Mississippi River’s role in shaping history and local culture. Photo by Toby Saltzman

The road led to the antebellum Houmas House, built around 1829. Filled with period European and Asian artifacts, plus a Paul Gauguin painting, the Classical Revival style “Sugar Palace” showcases how river trade enabled plantation owner John Burnside’s opulent lifestyle. Nearby, the Great River Road Museum details how the Mississippi River shaped local culture. The lobby accesses The Inn at Houmas House as well as the West Feliciana Historical Society Museum dedicated to ornithologist James Audubon who painted many of his Birds of America series in riverside forests.

Stand Up and Cheer

Early next morning, a thick fog enveloping St. Francisville seemed to lift slightly when passengers were greeted by a high school marching band and cheerleaders waving pom poms. Their rousing greeting signified the importance of the economic boost steamboat tourists bring to the town’s economy.

As the oldest town in Louisiana’s eight Florida parishes that extend east from the Mississippi, St. Francisville was a thriving cotton port a decade before the start of the Civil War. A testament to bygone days, the streets are fringed with antebellum mansions interspersed with humble clapboard dwellings.

Among the local artisans at St. Francisville’s Old Market Hall, Catherine Rouchon is the jewelry designer and owner of Compass Rose. Her items include necklaces and bracelets crafted with original sterling silver-backed compasses used by stray soldiers to find their way. Photo by Toby Saltzman

As in every port, American Queen’s fleet of buses enables passengers to explore independently. The first stop, is the Old Market Hall. Dating from 1819, it was filled with local artisans waiting for visitors. Included among them was Catherine Rouchon, a jewelry designer and owner of Compass Rose. A certified gemologist and silversmith, Catherine mines pretty stones in Louisiana, Texas and Colorado to craft into necklaces and bracelets.

She explained that five generations ago, her ancestor left France for New Orleans. He married a Creole woman, started a vegetable farm on the Mississippi River’s west bank, and sold produce at New Orleans’ French market. In 1980, her grandfather resettled in nearby Clinton to start a dairy. Showing a cluster of tiny, silver-backed compasses, Catherine said she found them while foraging for gems. Made by Stanley of London these “button compasses” were sewn into the hem of a soldier’s clothing as a hidden escape tool in case of capture. Engaged by Catherine’s story, I bought a compass strung on a necklace of tiny stones.

Historic Natchez was spared from destruction during the Civil War, mainly because it sided with the Union. Among the town’s over 600 restored antebellum homes, Stanton mansion is prized for its exuberant architecture and period furnishings. Photo by Toby Saltzman

That evening’s program featured river historian Lee Hendrix who spoke of “living Mark Twain’s dream” as a young deckhand in 1972 before graduating to river pilot. Knowing every turn of the river, Lee explained the challenges of navigating during night, fog or turbulent currents meant learning “to read the face of the water as if it were a book with cherished secrets.”

Returning to my room via the outside deck in the solitude of night, with moonbeams caressing the river’s waves, and the thrum of the paddle wheel the only sound, I imagined the river’s romantic pull over time, captivating thousands of youngsters to ply its course.

Natchez, Mississippi

The first port in Mississippi, Natchez was inhabited by Natchez Indians since the 8th century. Founded in 1716, Natchez was the southern frontier of the old Natchez Trace. This route has evolved to the Natchez Trace Parkway, a 444-mile scenic road marked with historic sites that ends in Nashville, Tennessee.

Natchez history – including its evolution from a plantation economy to civil rights to its rich music legacy – is documented at the Natchez Visitor Center, the Natchez Museum of African American History & Culture and the Forks of the Road Slave Market.

Spared Civil War destruction due to its pro-business Union support, Natchez abounds with over 600 antebellum homes that stand in elegant repose 200 feet above the Mississippi. Before exploring, I sought inspiration from local resident Regina Charboneau. While cultivating the town’s vibrant culture, the famed chef, restauranteur and author – dubbed “Biscuit Queen of Natchez” – had become Culinary Ambassador for American Queen Voyages. Charboneau suggested starting at Stanton Hall. Built by cotton merchant Fredrick Stanton, the 1857 Greek Revival mansion housed Union Troops during the Civil War. Today this National Historic Landmark is an antique-filled museum.

Adjacent to Stanton mansion, the Carriage House restaurant is famed for local specialties, including Creole shrimp salad and Southern fried chicken. Photo by Toby Saltzman

Over lunch of Southern fried chicken and Creole shrimp salad at the adjacent Carriage House Restaurant, I learned Natchez’s diverse history includes the South’s historic Jewish community, founded in 1843, who helped build the town.

A short walk away stands The Big Muddy Inn and Blues Room. This eclectically designed B&B with an attached music hall is owned by Tracy Alderson. Her ancestors arrived in Virginia on the first ship from England and became Daughters of the American Revolution. Musician Amy Allen is the second owner. Her father hails from “at least three generations of Louisiana settlers.” Allen’s rocking musical performances regularly entertain steamboat passengers.

The streets of Natchez appear to have changed little since the Civil War ended 158 years ago. One of the more dramatic sites is the 1830 First Presbyterian Church. It’s easy to imagine Samuel Langhorne Clemens sitting inside its sanctuary, mulling over local characters to describe in his writings.

Vicksburg Remembers

The most historic river port on the lower Mississippi is Vicksburg. Most paddle boats, including the American Queen, stop there, as do most of the motorists on the Natchez Trace Parkway. The first stop for just about everyone is the Vicksburg National Military Park run by the National Park Service. Like Natchez to the south, Vicksburg sits on the bluff overlooking the Mississippi. Originally fortified by Confederates with entrenchments and artillery batteries, the city once called the Gibraltar of the South surrendered to Union forces after a 47-day siege on July 4, 1863. It was the same day Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was defeated at Gettysburg. After the war, Vicksburg lived under federal military rule until 1868. Not until 1945, 82 years later, would the citizens of Vicksburg celebrate American Independence Day.

Among passengers on the “On the Front Lines of the Civil War” tour, a family including three generations hoped to find their ancestors’ graves. Vicksburg Battlefield Visitor Center provided orientation maps.

Entering the park, everyone turned silent, sensing its hallowed grounds honor the sacrifice of 17,000 soldiers. After climbing the steps of the Illinois State Monument for awesome views of battlegrounds dotted with canons, we followed the 16-mile road weaving through 1,300 monuments and markers of both Union and Confederate lines. Along the way, our park guide, Myra Logue described the complex siege of Vicksburg. When someone asked how park organizers knew which turf held Confederate or Union soldiers, Myra said, “Right after the war, soldiers returned to mark their positions.”

While returning to Vicksburg – notable for Mississippi’s finest collection of antebellum architecture – I asked Myra what inspired her to be a guide. “I’m a fourth-generation Vicksburg resident,” she said. “After the Civil War, my husband’s great, great grandfather bought land in Vicksburg for pennies an acre when no one wanted it and started a dairy farm. We sold it, and now I make a living off cruise tours.”

Curator and director of the Old Court House Museum, George “Bubba” Boom engages with visitors to help them trace their genealogy or locate the resting place of a fallen Civil War soldier. Photo by Toby Saltzman

At the river’s edge, floodwall murals illustrate Vicksburg’s history and culture. A short walk from shore, the Old Depot Museum depicts the Siege of Vicksburg in a battlefield diorama.

The Old Court House

Today Vicksburg’s Old Court House, a colossal 1860 edifice which miraculously survived Union army shelling and a 1953 tornado, houses Vicksburg’s history museum. Up a steel staircase, its courtroom is a time capsule of 1880s justice complete with judge’s bench, witness stand and jury seats. Though it evokes movies like To Kill A Mockingbird and Twelve Angry Men it was never a film set.

Downstairs is a book-lined space that turned out to be the private office of George “Bubba” Bolm, curator and director of Old Court House Museum. The books comprise the McCardle Library of original pre-Civil War volumes, maps and images, plus diaries of Union and Confederate soldiers.

Bolm said, “Walking through this building is walking in the footsteps of famous Americans, including Theodore Roosevelt, Jefferson Davis, Booker T. Washington, and Ulysses S. Grant.” He explained people come to trace their genealogy or find a grave.

Heading downhill, I stopped at the circa 1870 Church of the Holy Trinity, considered Mississippi’s finest example of Romanesque architecture. Sitting on a wood pew amid 26 stained glass windows I imagined Vicksburg residents’ stoic resignation that must have followed the South’s defeat.

Lounging on deck the next day – enjoying views of the wooded shoreline, sandbars thriving with birds and long cargo ships navigating tight turns – I reflected on my Mississippi River experiences.

Mark Twain impersonator Lewis Hankins regaled the audience in the Grand Saloon with quips and legends as he told the writer’s life story. We learned Clemens chose his pen name from the steamboat measure that “mark twain” or 12 feet depth of water meant the river was considered safe. Hankins said, “Clemens figured Mark Twain was a good name to hide behind.” Photo by Toby Saltzman

The 436-passenger American Queen had cultivated historic context while showcasing local culture. We had relished New Orleans jazz, tapped toes to guitarist Will Kiefer and his band, heard Clemens’ quips from a Mark Twain impersonator and were awed by legendary Beale Street singer Joyce Cobb. As the red paddle wheeler thrummed upriver toward Memphis, it struck me the Mississippi River flows with sounds and stories emblematic of America’s past and present. Envisioning Mark Twain penning prose as he “mastered the language of this water,” I couldn’t imagine a better way to experience the river than on the world’s largest authentic American Queen steamboat.

American Queen’s forward deck offers vast views of the Mississippi River by day and night. Photo by Toby Saltzman

To schedule a cruise on the lower Mississippi River, visit American Queen Voyages. For a detailed look at Mississippi River ecosystems visit Vicksburg’s Lower Mississippi River Museum. or Tunica’s River Park Museum.

Toby Saltzman is a Toronto-based writer who has won both gold and silver Lowell Thomas Travel Journalism awards.