An Arab dhow, a Shia mosque, and traditional waterfront architecture hug the harbor of Matrah, the commercial port for Oman’s capital, Muscat. The area immediately behind the mosque houses Oman’s Lowati community, of Indian origin. Photo by Charles Cecil.

By Charles Cecil

It was 5:25 AM when the voice of the muezzin from the mosque next to my hotel woke me. I lay there, listening, waiting for the line I knew was coming: “As-salaat khairin min an-nom.” “Praying is better than sleeping.” I lay there, momentarily debating the issue.

I had arrived the night before, directly from the States with a brief airport layover in Europe, so the idea of extra sleep was appealing. I wasn’t Muslim so I wasn’t going to go to the mosque. But I was where I wanted to be—in a small Muscat hotel overlooking Oman’s Matrah harbor. I shifted in the bed and in a triumph of resolution placed my feet on the floor. The towns are interesting, but it was the countryside I wanted to see. Oman’s scenic terrain, combined with its peaceful internal security, is like nothing else on the Arabian peninsula.

In recent years Oman has become known for its luxurious beach hotels or its five entries on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, one of which is the traditional, historic system of irrigation channels called aflaj that carry water from high mountain aquifers down through narrow valleys, irrigating agricultural fields in its descent. Less well known than the beaches or numerous historical forts are mountain valleys called wadis, narrow canyons penetrating the Omani mountain chain that reaches an altitude of just under 10,000 feet. Some are densely populated, wide, and easily entered. Others are narrow and steep, with little perch for settlements. Each has its own character and personality.

The pleasure of driving or hiking in Oman’s wadis is one no other country on the Arabian peninsula can equal. Though Yemen has higher mountains it has been in a state of civil war since 2014 and has never had the money available to build tourist infrastructure meeting the needs of Western travelers. Jordan has historic Roman, Nabatean, and Christian sites but its highest mountain barely reaches 6,000 feet.

Into the Countryside

After breakfast, I postponed any thoughts of shopping for frankincense or buying jewelry in the Matrah market (suq) and contacted my pre-arranged guide, Yahya Al-Harasi. I lived in Oman almost twenty years ago while working at the U.S. Embassy. I came back, interested to see how Oman was preparing itself to exploit its great potential for tourism. The government made Yahya, an employee of the ministry charged with promoting tourism, available to me for several days of my stay. We were soon on our way out of town, headed for the interior.

We drove westward from Matrah, Muscat’s commercial port area, first about 45 minutes along a four-to-six-lane divided highway, then turned inland (southwards) another 40 minutes on an excellent, wide two-lane road gently rising up a wide dry water course to a turn-off at the village of Al-Awabi.

An irrigation canal or falaj, comes down the distant mountain providing water for the terraced fields of Wadi Bani Kharus. Photo by Charles Cecil

Now we were entering Wadi Bani Kharus, one of Oman’s many dry stream beds (probably the best translation for “wadi”), curving and weaving into the interior of the Jabal Akhdar, or “Green Mountain.” The height of the mountains draws moisture out of the air, making this area the best-watered portion of Oman. As one rises in elevation temperatures fall, assuming a milder Mediterranean quality.

Twenty years ago, this had been a rutted road, advisedly entered with four-wheel drive. Today a good asphalt road heads up a flat gravel outwash toward the mouth of a canyon. These mountains form a long chain inland, parallel to Oman’s northern coast, giving the country a special character unlike any of its Persian Gulf neighbors.

Maintaining the Water Flow

Almost as soon as we entered the mouth of the canyon—perhaps 200 yards wide at the opening—we encountered a work crew about to open up a shaft leading to a falaj, or water channel, some 20 feet below the surface of the ground. Authorities do not agree on the origin of these aflaj (the plural form of the word); some postulate a Persian origin. Omani aflaj are known to have been in use as far back as 500 A.D., but archaeological evidence suggests that they may have been introduced as far back as 2500 B.C. They channel and conserve scarce water resources, leading mountain springs to cultivated fields or small settlements. Underground channels are connected about every 50 yards with a vertical shaft to allow periodic entry for cleaning.

Young man removing dirt and salt deposits from an underground water channel, or falaj, in Oman’s Wadi Bani Kharus. Photo Charles Cecil

As limestone deposits build up, they restrict the flow of water. The crew was chipping large slabs of salt-like encrustation into rectangular chunks and moving them up to the surface, restoring the underground channel to its original size. This is just one of the aspects of daily life you can see when you drive into an Omani wadi. Finding people at work in the fields is another. Weavers, both men and women, can be found in some villages, and are happy to sell their fabrics. Tracing water to its source always ensures an interesting outing.

First Encounter with Omani Hospitality

Khalid, the foreman of the work crew, insisted we sit with him for coffee and dates. The aroma of cardamom often added to coffee in Oman, alerted me to its subtle taste. After three thimble-sized cups (etiquette says three is the customary limit) we returned to our car and continued on our way for the 16-mile ride to the village of Al-Ulya, at the end of the paved road. Though we were in a four-wheel drive SUV there was no need for extra traction, but the high clearance of an SUV offers flexibility if you want to explore off-road trails leading to Instagram-able vantage points. Along the way, we passed several settlements where footpaths led into irrigated fields under a canopy of date palms.

Khalid, the foreman of the falaj cleaning crew in Oman’s Wadi Bani Kharus, pours coffee for unexpected guests. Photo by Charles Cecil

The fact that many roads into Oman’s wadis are asphalted shouldn’t make you feel that you’re on some tourist circuit. Wadi Bani Kharus, an easy two-hour drive from Muscat, is known for its beauty and easy accessibility, but during my all-day foray I didn’t encounter another non-Omani. Oman’s good road system is evidence of the government’s efforts to improve the quality of life of its people by making it easier to get to markets or hospitals in larger towns. But up to now the traditional ambiance one finds in these narrow mountain valleys is undisturbed by large numbers of visitors. Foreigners still seem to prefer visiting the numerous restored castles (Bahla is on the World Heritage list) or enjoying the beaches or the desert experience of the Wahiba Sands, a smaller version of Saudi Arabia’s “Empty Quarter.”

The valley narrowed as we progressed “upstream”, if that’s the right word to use when the flow is completely out of sight underground. Occasionally I could see long concrete channels snaking down canyons, invariably disappearing from view into a mass of date palms near the valley floor. These cement channels are the higher portion of the aflaj, picking up water from small mountain springs and carrying it downward to lower, inhabited areas where every drop is carefully directed to terraced plots on hillsides, eventually reaching the plots under the date palms. This centuries-old system of conserving and directing water enables residents of mountain valleys to cultivate fruits, vegetables and fodder for their livestock (usually sheep and goats).

Omani schoolboys getting onto the school bus. Photo by Charles Cecil

Along the way, we passed the single-story elementary school. The school follows a split-session system, girls in the morning, boys in the afternoon, so we saw numerous young boys playing soccer or other games as we worked our way up the wadi. Around noon the boys began to gather in groups, wearing their white dishdashas and carrying book satchels on their backs, as they waited for the small vans that serve as school buses to pick them up.

Human nature, I thought, must be formed through a process of interaction with natural surroundings. The inhospitable, barren mountainside seemed to produce a people overflowing with warmth and hospitality as if to compensate for the harshness of the terrain. It’s as if residents realize what hardships the traveler must have endured to reach them and instinctively offer shade and refreshment.

More Hospitality….

Al Ulya’s old residential housing overlooks the wadi floor of Oman’s Wadi Bani Kharus. Photo by Charles Cecil

After reaching Al-Ulya I asked permission to photograph a group of schoolboys as they waited in front of a house for the school van. Permission was quickly given, and I was then just as quickly invited to have halwa, the traditional Omani sweet, and coffee with the family’s Omani males on a terrace overlooking the hillside on which the house was built. Oranges then quickly appeared and were cut into quarters. I had been in the Wadi 18 years earlier, enjoying one of many weekend outings to familiarize myself with the country and its people, and to enjoy the scenery. I commented on the improved quality of the road, the number of new houses, the electricity power lines and the school. What more did they want from the government, I asked. “Better phone service” replied one young man, Hamoud Thalib, an army soldier home on a week’s leave, waving his cell phone at me. There are no phone lines into the wadi and the sides are so tall that Oman’s excellent mobile coverage barely reaches the wadi floor. Other than that, residents say they are satisfied with their quality of life.

Wadi Bani Kharus, Oman. Arab Hospitality: coffee, halwa (sweets), and oranges for a foreign guest. Photo by Charles Cecil

With some difficulty I declined an invitation to stay for lunch, stressing my interest in finding the main source of the wadi’s water. Unwilling to let me escape from Arab hospitality that easily, Hamoud offered to lead me to the spring, an offer Yahya and I gladly accepted. We drove a short distance to the end of the road and began an ascent, first through date palms, then fields of onions, garlic, and beans, pomegranates, apricots, and oranges, soon rising above the terraced, cultivated plots.

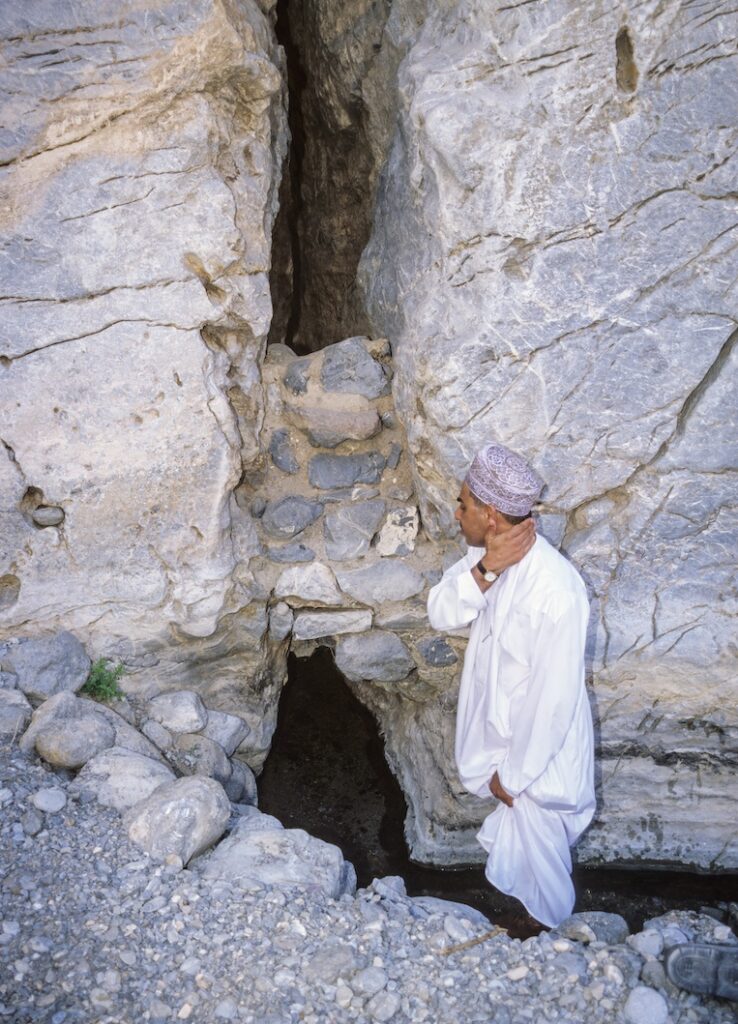

Open Sesame!

After a 45-minute climb, we reached the spring. It was almost a Biblical scene. A two-foot-wide cleft in a sheer rock wall face provided a steady flow of water from inside the rock. It was as if a genii had smitten the rock with a magic sword, commanding the water — “Iftah, ya Simsim!” (“Open Sesame!”) — to flow from the large chamber within.

An Omani refreshes himself with cool water issuing from a cleft in the rock in the narrow mountain valley of Wadi Bani Kharus. Water from such springs flows by gravity through a series of canals and channels, called aflaj (singular, falaj), to terraced gardens farther down the mountain valley. Photo by Charles Cecil

On our descent we followed a falaj along the wadi wall opposite the one we had ascended, stopping briefly at a man-made collection basin useful for watering livestock before following the channel on downward. Villagers still use the sun and a series of vertical markers—a kind of sundial called athar—to regulate the division of water, stopping certain channels periodically with rags and earth to direct the water down a different way.

On another day, in the settlement of Bani Bu Ali, I met an old man, Abdallah, who had driven in his pick-up to the athar to check the length of the shadows. Since I judged him to be older than I was I addressed him as “Ammie Abdallah “or “Uncle Abdallah”, a polite form of address to an older man. When I asked him why the farmers didn’t simply check their watches and apportion the water by the clock, he shrugged and said, “We’ve always done it this way.” Yahya agreed. “Tradition is slow to change,” he said. “The old way still works for these people.”

A Wealth of Wadis

Oman’s wadis are one of the great scenic resources of the country. Each has its character. Wadi Tiwi, on the coastal road about 45 minutes north of Sur, is narrow yet densely settled, with a narrow but graded and sometimes paved road going some 6-7 miles up the canyon. In his account of his travels, the 14th-century Moroccan Ibn Battuta praised Wadi Tiwi’s bananas when he passed through in 1368.

Wadi Shab, a few miles farther north, has no permanent settlements but is so well-watered that deep pools entice you to swim, especially if you are there on a hot day. The wadi contains many cultivated fields, whose owners walk in from houses near the mouth of the wadi.

As we made our way back down Wadi Bani Kharus, headed toward Muscat, I reflected on Oman’s wadi irrigation systems, which are on the World Heritage list. To make its interior more accessible to outdoor enthusiasts, Oman has developed a series of well-marked trekking trails. Many Muscat travel agencies can provide a car and driver-guide to any of the wadis.

Canal carrying water to agricultural terraces at the base of Wadi Bani Kharus. Photo by Charles Cecil

With two cars (or one car, with a separate driver and guide) you can arrange a traverse on foot across the eastern Hajar Mountains, entering up Wadi Tiwi, then connecting with Wadi Bani Khalid for the downward trek. This is a two-day, 20-mile hike cresting at about 7000 feet before exiting through Wadi Bani Khalid on the interior side of the mountains. Husaak Adventures can provide all camping equipment and food, setting up a campsite mid-way. Either Sur or Muscat can serve as your base for starting and ending this expedition or, if you want to head west afterward rather than back toward Sur, there’s an adequate small hotel, the Oriental Nights Rest House, where the road from Wadi Bani Khalid joins the main east-west road. Once reaching Wadi Bani Khalid you are also near the Wahiba Sands, a totally different terrain with touring and lodging options also available.

For serious and casual hikers plus those who prefer exploring in four-wheel-drive comfort, Oman’s wadis have something to offer everyone—but choose the cool months of the year, October-March, before the 100+ temperatures arrive. I went in February on my most recent visit and could easily have spent ten days exploring one wadi after another, with no fear of duplication or boredom. The annual Muscat Festival, a celebration of Oman’s rich cultural heritage attracts Omani families as well as foreign visitors, offering attractive demonstrations of Omani music, cuisine, traditional dance and handicrafts.

Safe, Peaceful, and Stable

Oman is an island of stability in an otherwise turbulent Middle East, ruled by a benevolent sultan, Sayyid Haythem bin Tariq Al Said, since January 2020, following the death of his predecessor, Sultan Qaboos. Prior to becoming sultan Sayyid Haythem was Minister of Heritage and Culture for 18 years and is committed to preserving and promoting Oman’s rich cultural heritage. The country has suffered only one terrorist incident in its modern history. This occurred in July (2024) when three Omani brothers, adherents of the fundamentalist Islamic State group, opened fire on Shia Muslims gathered to celebrate the Shia holiday of Ashura. Six died—an Omani policeman, an Indian, and four Pakistanis. The assailants were killed.

Omanis are warm and friendly by nature. They are conscious of their own security needs but not so obsessed with it that they regard foreigners as objects of suspicion. The country is stable, safe, and clean, and deserves to be better known. A wide variety of hotels and guest houses exists throughout the country, and travel agencies stand ready to provide guides and transport to any point in the country. Because of the relatively high standard of living, tourists are not hassled by would-be guides or vendors of trinkets as is the case in many other countries.

As a tourist destination, Oman is one of the world’s best-kept secrets. The government is now working to raise its profile. Go before it gets crowded!![]()

Charles O. Cecil is a retired U.S. Ambassador whose 36-year diplomatic career included assignments in ten Muslim countries, including Oman. His submissions for EWNS include a Featured Photography essay on Bhutan and a guide on what to observe when visiting a mosque.