“Three cities, two countries, one region”, remarked former Texas State Senator Jose Rodriquez referring to El Paso Texas, Ciudad Juarez and Chihuahua Mexico, the United States and Mexico. The saying is something you hear a lot in these parts, especially when it comes to El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, the Mexican city just across the Texas border. It’s about a 15-minute walk over a pedestrian bridge connecting the two cities, and the link is both real and symbolic. For the cities have been joined since their inception. Their language, jobs and cultures have been blended since before Mexico and Texas existed.

“Before 9/11 you didn’t even need a passport”, recalled Bernie Sargent, local historian and former chair of the EL Paso Historical Commission.

El Paso and Juarez Are Linked by History

El Paso and Ciudad Juarez were once part of a 17th century settlement founded by Spanish Friars. Even their names were interchangeable. What is now Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, was called El Paso de Norte. Only after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which made the Rio Grande the border between Texas and Mexico, did the two towns fall into different countries. In 1850, the name El Paso was given to what was then a small cattle and railroad town on the north side of the Rio Grande. In 1888, the name Ciudad Juarez was given to what used to be El Paso del Norte.

“El Paso presents a blend of Southwest Texas and Mexico that’s hard to find elsewhere”, notes historian Sargent. In this, the largest border community in Texas, some 80% of the people are of Hispanic heritage. Ciudad Juarez, just over the bridge, is much closer to Texas than it is to faraway Mexico City. And El Paso is closer to the capitals of Arizona, New Mexico and Chihuahua (Mexico) than to Austin. Surrounded by mountains and desert, both towns have a sense of remoteness.

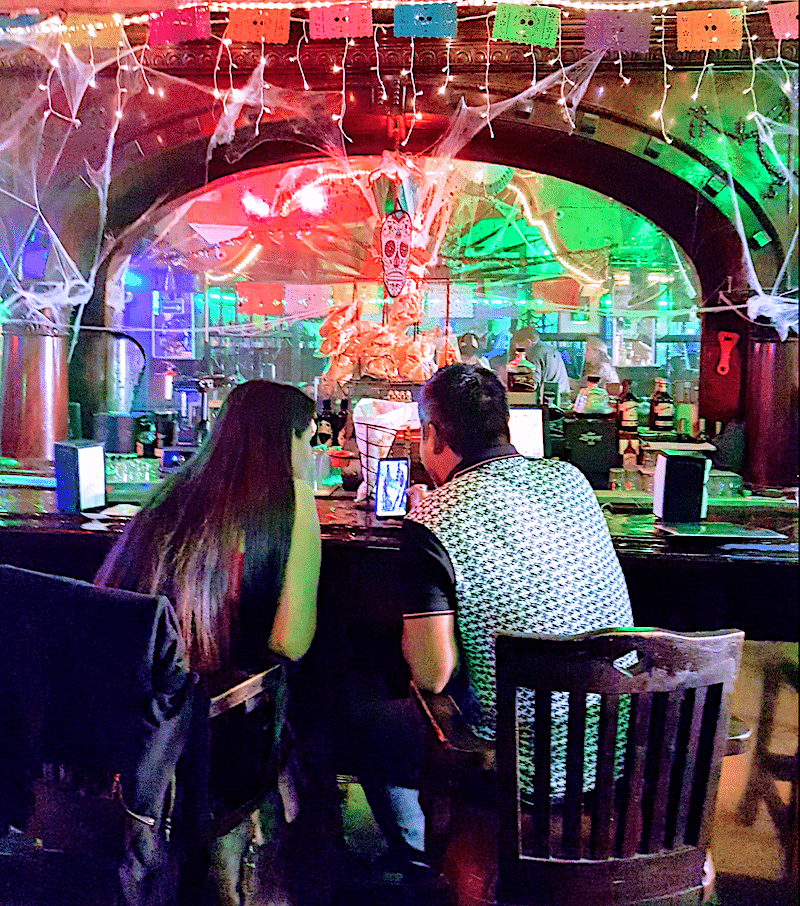

In mid-October, the Kentucky Club is decorated with Dia de los Muertos signage. It’s a great place to escape from Halloween north of the border. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

I pondered this over a Margarita at The Kentucky Club Bar, a ten-minute walk from the bridge entrance to Mexican. I passed pharmacies whose prices intended to lure American visitors. But most of the stores selling clothes, food, and other household seemed geared to residents.

The legendary Kentucky Club opened before US Prohibition and has long been a hub for El Pasoans and a go-to place for visitors, some of them famous: Ernest Hemingway, Frank Sinatra, and Marilyn Monroe all drank here.

The Kentucky Club stayed open even during the dangerous years of 2009-2012 when warring drug cartels gave Ciudad Juarez the highest murder rate in the world. By 2010, some 8,000 businesses were victims of extortion. At that point, the army was called in and Carlos Salas took over. The new state attorney general ordered the Chihuahua State police to create an anti-extortion squad. The city’s police force was purged of corrupt cops and those who did little besides picking up a pay check. The new law enforcement squad was soon rewarded with new patrol cars, weapons and new uniforms. The city even opened a new country club for officers and their families.

The police began patrolling the streets and crime dropped markedly. A few years later, the city started announcing that Juarez was safe for tourists, with the noticeable presence of police on the streets. (In mid-2020, violence erupted again with 90% of the victims involved in gang battles.)

Juarez had a poster boy in former Congressman and presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke, who had his first – and arranged – date there with Melissa Sanders. They had a drink at the Kentucky Club, went on to dinner, and ended the evening with a visit to the Cathedral. Three months later they were engaged.

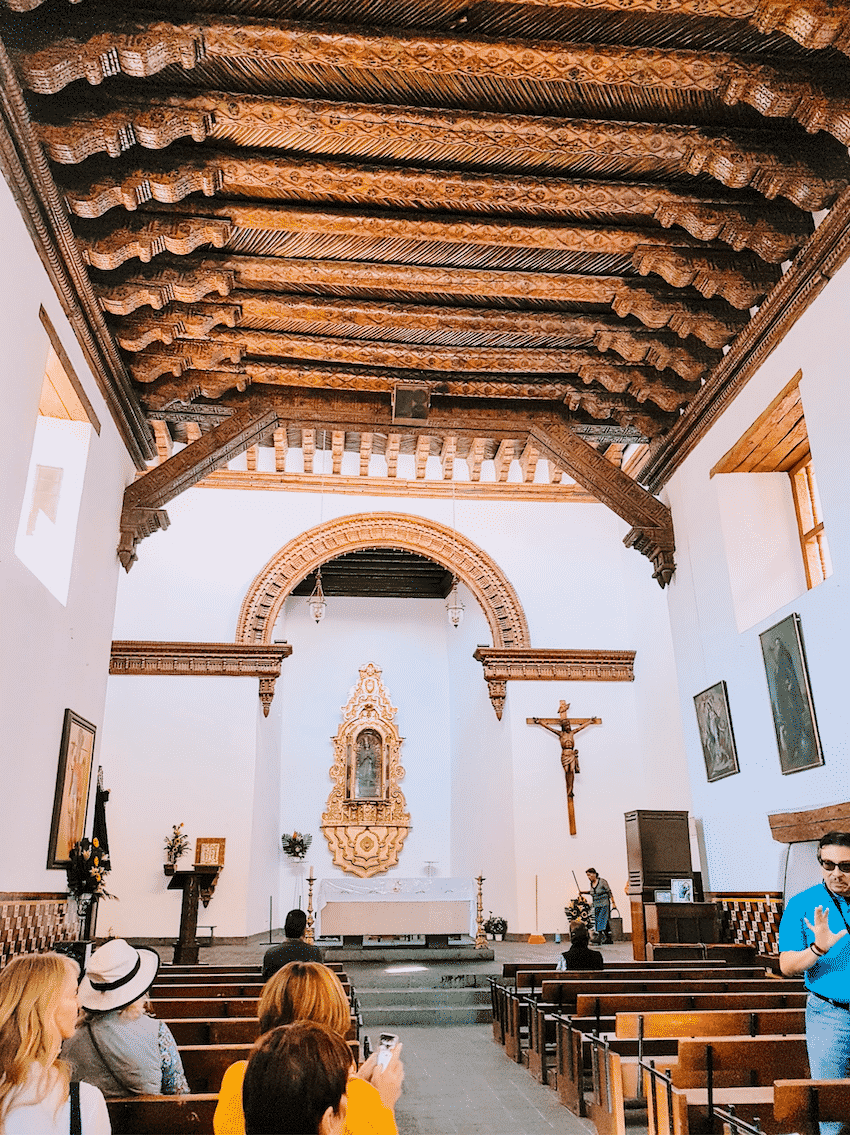

In the city of Juarez, the Our Lady of Guadalupe Cathedral is regarded as a local treasure by the population. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

Our Lady of Guadalupe Cathedral and the Mission next door make it one of the most authentically Mexican border towns. The Cathedral was rebuilt in the mid-20s but the stained-glass artworks are original. The Mission, one of the oldest in the region, was the first building erected in El Paso del Norte in 1659, some two hundred years before it became Juarez. Much smaller than the Cathedral, it has a centuries-old feel and features a carved wood ceiling.

Outside is the Plaza De Armas a delightfully festive park that swirls with food vendors, jugglers and the sound of guitars. Sit next to the bandstand and enjoy the parade of locals strolling past the fountain with a bronze statue of the revered comedian, actor and singer, German Valdes, who portrayed a character called Tin Tan in over 100 Mexican films. Have a refresco and a roasted ear of corn before heading to the nearby Mercado with stalls selling everything from jewelry to food to tourist souvenirs.

The Mercado is not far from a must-visit place, The Museum of the Revolution on the Border (El Museo de la Revolucion en la Frontera). Housed in an artfully renovated former customs house, the museum takes visitors through the pre-revolutionary time of dictator Porfirio Diaz and the opposition to his rule led by folk heroes Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. Displays show drawings and newspaper accounts, songs and paintings of this culturally fertile time in Mexico’s history. There’s an emphasis on photography, and display cases show old cameras and describe the photographers who came to capture Mexico’s struggle.

In the past, just as today, there was a connection to the town just over the border. “El Paso is where the Mexican Revolution was born”, remarked Jose Rodriguez, the Texas State Senator whose district includes El Paso. “Pancho Villa came to El Paso to eat ice cream and buy weapons”, he added.

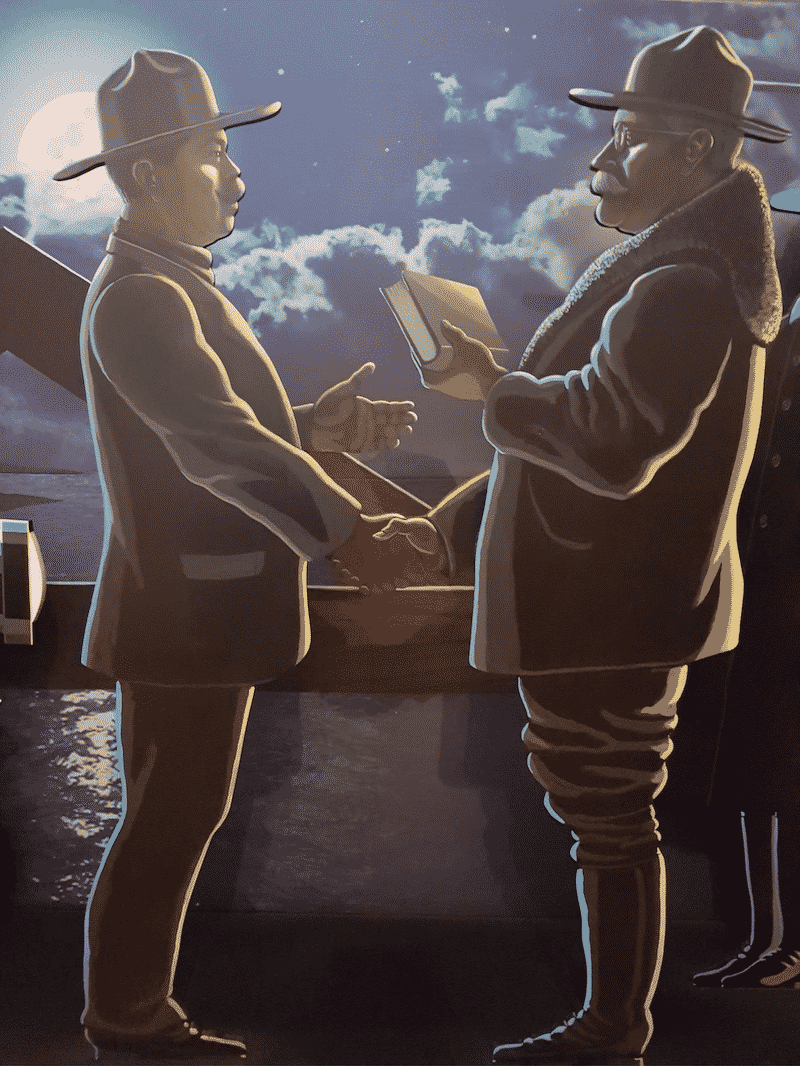

A drawing in the Museum of the Revolution depicts Porfirio Diaz and then US President William Howard Taft shaking hands on a bridge spanning the Rio Grande. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

One stand-out visual in the museum is a drawing of Porfirio Diaz and then US President William Howard Taft. They are shaking hands to mark an historic meeting, the first between a US and a Mexican president. It began on Oct, 19, 1909, in El Paso. After holding a presidential breakfast at the St. Regis Hotel, Taft met Porfirio Diaz for a private meeting at the Chamber of Commerce Building and then together they crossed the border to the customs house (now the Museum of the Revolution) in Juarez. There were lavish gifts, decorations inspired by the Palace at Versailles, and crowds of people outside. No treaties were signed. Perhaps Diaz wanted to shore up his power. If so, the meeting failed, for nineteen months later he was deposed.

I was struck by the hotel in El Paso where Taft began the historic meeting. The St Regis Hotel, built in 1905, was considered one of the finest in El Paso. By the time of the Taft Diaz meeting the railroad town was booming. From glamourous hotels to bordellos, saloons and gunfights, it earned names like sin city and was called the “Gunfight Capital of the World”. Its Wild West origins can be seen in the Concordia Cemetery, where the notorious outlaw John Wesley Hardin is buried.

Twentieth century wealth brought a series of grand buildings that both remind the visitor of the past and offer a hopeful blueprint for El Paso’s’s future. But as the century drew to a close, it was hard to see much of a future for the city. El Paso’s downtown, like many US cities, was largely abandoned, with crumbling buildings and parking lots. The 1994 NAFTA agreement didn’t help. As manufacturing moved over the border, blue collar jobs were lost to El Paso.

Only in the last decade has a well-funded civic improvement movement begun to change the face of downtown. It’s still a work in progress, but there are now improved bus lines and a streetcar – retro in appearance, modern in function. A new baseball stadium next to the Convention Center brings hundreds of thousands of Texas League baseball fans to see the El Paso Chihuahuas. San Jacinto Plaza, the city’s downtown meeting place, with sculptures and festivals, has been refurbished. Nearby, the Plaza Theatre, built in flamboyant Spanish Revival style, and with one of the few remaining Wurlitzer organs in the world, is open for festivals, films and theatrical productions.

Many of the architectural treasures were designed by the firm of Trost and Trost, which deserves to be better known. Architect Henry Trost moved to El Paso in 1903. His work in the Southwest included office buildings, hotels and homes in a multitude of styles ranging from Prairie and Art Deco to Spanish Revival and Moorish. Of the 650 buildings designed by his firm over one third were in El Paso.

“El Paso is a showcase of architectural styles like few other cities,” adds historian Bernie Sargent, who heads the Trost Society, which offers walking tours of El Paso and trips to Trost buildings outside the city.

The Art Deco Hotel Paso del Norte, now 108 years old, welcomed presidents and cattle barons, and was considered the most luxurious hotel between Dallas and Los Angeles. Another treasure, the 1929 Trost-designed Plaza Hotel was one of the first high-rise hotels built by Conrad “Nicky” Hilton, Jr. He and his wife, Elizabeth Taylor, lived briefly in the penthouse.

Dozens of vendors selling clothes, blankets and other souvenirs are located in and around the Mercado in Ciudad Juarez. Photo: Jacqueline Swartz

Sitting on a bench in the San Jacinto Plaza, I watched caterers set up food for an event in a white tent. On the surrounding streets, I saw building sites. But instead of the usual boxy condos, these were classic structures under renovation. I was drawn to a 1920’s Art Deco office building and a striking-looking building designed in an unusual mixture of Art Deco and Moorish styles.

Both buildings – the first is the Mills Office building – were bought in 2019 by oil billionaire Paul Foster. He keeps buying and restoring buildings (he also owns the Plaza Hotel and others) and is helping to save El Paso’s heritage.

The Moorish-looking Kress building opened in 1907 and used to house Kress and Co., a chain of five-and-dime stores. Samuel H. Kress, an avid art collector, donated a collection of 57 European paintings from the 13th to the 18th century to the city on condition that there was a museum to house them. They now make up the permanent collection of the El Paso Museum of Art, which is a few steps from the San Jacinto Plaza. Who could imagine that you can see a Canaletto or Van Dyck in El Paso.

A few yards away is the Museum of History, which boasts the only interactive digital wall in the country. It tells the story of El Paso and responds to specific questions.

When it comes to food, El Paso has plenty of traditional Tex/Mex restaurants. But the downtown area is upping its game, and there’s no better example than the restaurant in the city’s artfully renovated Stanton hotel. The century-old Trost-designed four-story hotel features a four-level light well and moving light sculptures. The restaurant, which is off the lobby, feels part of the hotel. It was created by Chef Oscar Herrara, who is known for the Flor de Nogal Hacienda in Juarez. The menu is Mexican/European fusion, with dishes like a starter of Aguachile, consisting of passion fruit, sunchoke, jalapeno, striped bass, and aioli. Chef Herrera’s artichoke and ribeye tacos already are a fine dining classic. The name of the restaurant, Taft Diaz, speaks to the connection between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez.

Standing on the site of the 1827 Ponce de Leon ranch, the Mills Building was constructed in 1910-1911 by Trost and Trost, who moved their architectural offices there for a decade. The building was the second reinforced concrete skyscraper in the US. Of course at that time, the 154 ft, 12-story building could qualify as a skyscraper. Photo: Jacqueline Swartz

I decided to follow the Trost trail some 220 miles from of El Paso to the tiny ranching town of Marathon, population under 500. This is quintessential West Texas, hot, arid, with long ribbons of highway surrounded by mountains and the Chihuahua Desert. My destination was the Gage Hotel, a theatrical, award-winning boutique hostelry opened in 1927.

The Gage has an adobe courtyard with 20 guestrooms surrounding a pool and fountain. These ground floor rooms seemed to me like a surreal cattleman’s fantasy with cow horns on the walls and leather upholstery. Old doors and window frames come from abandoned Mexican churches.

Both Conde Nast Traveler and Texas Monthly rate the Gage as one of the top ten hotels in Texas. Margaritas served at the hotel’s White Buffalo Bar were named ‘best in Texas’ by Sauveur Magazine.

Outside it was dark, very dark. This is no accident: the hotel has earned a Level I Dark Sky designation. And the darker the sky, the brighter the stars. Forty minutes away Big Bend National Park has the darkest measured night skies of any national park in the country. The “bend” refers to the Rio Grande, as it continues to mark the border.

I visited the Big Bend Museum on the Sul Ross State University campus in Alpine. It’s a modern, well-designed structure that shows the area’s history and is as much about Mexico as Texas. I was drawn to a series of maps spanning five centuries, the oldest dating from 1561. One particularly striking map showed how the region looked after the Mexican American War that ended with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty ceded to the U.S. the Mexican territories of California, Nevada, Utah and Colorado plus half of New Mexico and most of Arizona. In return, Washington paid Mexico $15 million dollars.

The map showing the pre-treaty area underscored the fact that in the mid-1800’s, it was hard to know where Mexico ended and the U.S. began. It made me think of Juarez and El Paso and realize that links forged by a shared culture and language live on despite conquest and compensation.![]()

Jacqueline Swartz has written about travel, culture and health for major publications in Canada and the US.