Detroit Emerges from Bankruptcy, but Recovery will take Years

Detroit’s young workers gather at Campus Martius park at day’s end to network before heading home to downtown lofts and apartments.

For close to a century the Forest Arms apartments was one of the most prestigious addresses on Detroit’s near Westside. But by the start of this decade Detroit’s declining population, municipal mismanagement and foundering economy had left the building reminiscent post-war Berlin

The city ordered the structure demolished, but 48-year old local contractor Scott Lowell objected and eventually won the right to renovate the decimated 1905 Edwardian with 70 eco-friendly apartments, many with stunning views of the city.

The Forest Arms is the third blighted building Lowell has transformed and like the previous two it will be fully occupied the day it opens.

“I regard myself as a steward of this city and buildings like this are worth preserving,” Lowell says as he walks up a once majestic staircase in the process of being repaired. “Young people without the baggage of the past are moving to Detroit and they want to live in historic buildings close to where they work.”

In the nine months since Detroit emerged from a 16-month Chap. 9 bankruptcy, the mood of the city has shifted from stoic despair to guarded optimism. Weekly openings of new restaurants, galleries and designer shops are creating a buzz that’s impossible to deny. The streetlights are back on along Woodward Avenue, where track is being laid for a light rail commuter train 90% financed by private investors. Ambulances and police cars now respond when summoned. Midtown Detroit recently acquired the sine qua non of gentility: a Whole Foods market.

Many factors contribute to the upbeat mood but perhaps the biggest is the revival of the auto industry. Over 17 million vehicles will roll out of dealer showrooms this year, no doubt increasing the $7 billion in collective net profits the Big Three earned in 2014. Recently, the United Auto Workers and General Motors began negotiating a new contract which likely will result in new hires and higher wages.

Despite impressive progress, Detroit still has plenty of problems. The downtown area may have a 98% occupancy rate but residential neighborhoods look as if they’ve been winnowed by 1,000 tornados. There are so many vacant lots that the houses that still exist almost seem like homesteads. Derelict but still habitable houses still can be bought for as low as $600, but there are few buyers among the 680,000 people (down from 1.85 million in 1960) who still call the city home. Bargain hunters often are deterred by blight. Of Detroit’s 380,000 homes, some 114,000 have been razed with an additional 80,000 scheduled for demolition. “Blight is a cancer,” Detroit’s Blight Removal Task Force noted in a 2014 report. ”Blight sucks the soul out of anyone who gets near it, let alone those who are unfortunate enough to live with it all around them.”

Detroit hit its nadir under Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick who resigned in 2008 after pleading guilty to legal, sexual and administrative malfeasance that included perjury, obstruction of justice and the diverting of $10 million of city money to hide an extramarital affair with his chief of staff. Despite using a city credit card to buy $210,000 worth of restaurant meals, wine and spa massages during his first term, Kilpatrick managed to remain in office more than six years by exploiting the prejudices separating suburban whites from inner city Afro-Americans. Ordered to repay the city $1 million, Kilpatrick was sent back to jail for attempting to hide assets from the court. In 2013 he was sentenced to an additional 28 years after being found guilty of mail fraud, extortion and racketeering.

Ironically, heavily Democratic Detroit owes its resurgence in part to Republican Gov. Rick Snyder, who in March 2013 declared a financial emergency, appointed an experienced manager to take control of the city and told him to file for bankruptcy so Detroit could get out from under liabilities in excess of $18 billion.

One immediate problem confronting Detroit was a $290 million debt to Bank of America, Merrill Lynch and UBS resulting from risky investments made by Kwame Kilpatrick. Instead of investing in extra police, fire protection and road repairs, the city was using 5% of its shrinking budget to service the debt. The banks initially agreed to accept $230 million, then dropped their demand to $165 million after intense negotiation. But when the federal mediator presented the compromise to Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes, he rejected the deal, saying the price was too high for a debt that was likely illegal. Chastised by Rhodes, Detroit’s negotiators returned to their creditors and threatened to sue, at which point the banks caved and agreed to settle for $85 million.

Unfunded pension liabilities constituted the most troubling hurdle since the only municipal assets large enough to secure them consisted of paintings valued at $816 million at the city-owned Detroit Institute of Art (DIA). Detroit’s art was saved thanks to a “Grand Bargain” in which foundation pledges of $366 million were matched by $350 million from the State of Michigan and $100 million from private DIA benefactors.

To make any deal work, however, pensioners had to accept cuts and promise not to sue. In the end non-uniform former employees did just that, agreeing to accept a 4.5% cut and forego future cost of living adjustments. Police and firemen retained full pensions but gave up half of future cost of living increases.

“Bankruptcy allowed the city to eliminate liabilities, clear its balance sheet and achieve a different narrative,” says Eugene Driker, a Detroit attorney who served on the federal mediation team. “It was a near death experience from which the city emerged with a well-founded optimism that didn’t exist before.”

After decades of mismanagement, Detroit finally has competent leadership in the person of Mike Duggan. A white politician elected Mayor by a city that’s 82% black, Duggan’s popularity soared when after taking office in January 2014 he promised to double the number ambulances, create an affordable car insurance program, reopen 220 parks and crack down on thieves stealing metal from abandoned homes. His most notable accomplishments, however, are replacing more than 35,000 broken streetlights and hastening the removal of blighted homes from 200 a year to 200 a week.

One of Duggan’s biggest supporters is billionaire Dan Gilbert. “If a white country elects a black president why can’t a black city have a white mayor, asks Gilbert? “It’s a great thing for America. Now we have a Democratic mayor who actually talks to the Republican governor. They work together to solve problems.”

Politicians working together may have enabled the city to escape bankruptcy but it is the private business community that is bringing Detroit back to life. Detroit native Gilbert, who is the founder and chairman of Quicken Loans and Rock Ventures and majority owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers and some 110 other companies, started the movement back to the city in 2010 when he moved 1,500 employees downtown from offices in five suburbs. Within six weeks he realized the city was where he and his young employees wanted to be.

“You could feel the energy,” he remembers. “Detroit had a real urban core where young people wanted to work and live. A revived Detroit meant that graduates from Wayne State, MSU and Michigan wouldn’t have to relocate to Chicago or New York to find a good job. They could come here and be part of history”

Gilbert certainly has made staying closer to home more attractive. This year 20,000 students applied for 1,800 internships at Quicken.

It did not escape Gilbert that most of downtown could be purchased at fire sale prices. Architectural gems by designers like Albert Kahn, Minoru Yamasaki and Daniel Burnham, co-author of the city-shaping Chicago Plan of 1909 and architect of New York’s Flatiron Building, were available for as low as $8 per sq. foot. Today, Gilbert owns 75 buildings, most of them filled with 12,500 Rock Ventures employees and 130 corporate tenants to whom he leases space.

Downtown Detroit looks like an enormous construction site. Stately old buildings are gutted and rehabbed beside trenches being cut for fiber optic cable that will bring high-speed internet to the entire Central Business District. Sofas and coffee tables sit outside office towers so Millennials can eat lunch in the sun. Were it not for the jackhammers, Detroit would feel like a campus during pledge week. The kegger vibe continues after work when hundreds of young professionals head to Campus Martius, a downtown park where they flirt and network before going home on streets with surveillance cameras monitored 24/7 in the Quicken control center.

“Great things are happening here,” beams Bruce Schwartz, the self-styled “Detroit Ambassador for Quicken Loans. “What these young people are doing will be written about in history books.”

The most significant factor shaping the city’s future is the revival of manufacturing in the form of companies like Shinola, a storied brand once famous for shoe polish that today makes bicycles, leather goods and wristwatches priced from $450 to $600 at the entry point of luxury. Located behind the old GM headquarters, Shinola’s factory employs 300 Detroiters, half of whom assemble the only watch made in America. “We believe in the beauty of industry, the glory of manufacturing,” the company says on its website. “We know there’s not just history in Detroit, there is a future. It’s why we are here. Creating a community that will thrive through excellence of craft and pride of work. Where we will reclaim the making of things that are made well. And define American luxury through American quality.”

When Shinola’s first 2,500 watches hit the market in 2013 they sold out in eight days. This year the company expects to sell between 150,000 to 180,000 watches through its eight retail outlets and stores like Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom.

“Shinola’s goal is to reestablish the Made in Detroit brand,” says Bridget Russo, the company’s chief of marketing. “We take enormous pride in the fact that our products look great and are made here.”

A number of factors limit Detroit’s speedy recovery. Though Michigan’s out migration has been reversed, Detroit continues to lose population. Thirty-eight percent of its residents live below the poverty line and are plagued by murders that occur in numbers close to New York’s, a city 12 times larger.

Equally problematic is what to do with all the vacant land after blighted structures are carted away. Detroit covers 139 sq. miles, an area large enough to accommodate Boston, Miami and San Francisco combined. Some state economists believe the land should stay fallow or be used for urban farms, rainwater catchment basins. Dan Gilbert disagrees. “I’m not a big believer is downsizing,” he says. “If you are downsizing you are dying.”

Gilbert believes cleared residential lots have tremendous value because sewers and utilities already are in place. He advocates bundling vacant property into greenfield neighborhoods that can be given away free to developers willing to build a $5 million police substation and $20 million public school on part of the land they receive. “This development model worked in Brooklyn and can succeed here,” he says. “I see no reason why Detroit can’t have a 1,000,000 population in the near future.”

Already there are signs that suburban attitudes about Detroit are changing. “People are driving down from places like Bloomfield Hills to have bridal showers and rehearsal dinners here,” says Carolyn Howard, owner of the Traffic Jam restaurant close to the historic buildings being renovated by Scott Lowell. Adds Howard: “The suburbs want to be part of the new Detroit experience.”

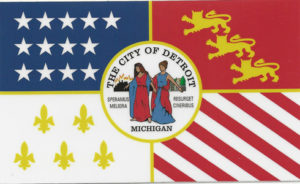

Two centuries ago, Detroit leveled by the great fire of 1805. The seal of the city that arose from the ash depicts two women: one standing before a heap of cinders, the other astride a skyline of tall buildings. Both are bracketed by the words, Speramus Meliora. Resurget Cineribus. We hope for better things. It will rise from the ashes. Citizens of Detroit are hoping that the determination of the past can be the dream of the future.![]()