Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes in Idaho | Photo by Lisa James | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

By Alexander Eisman

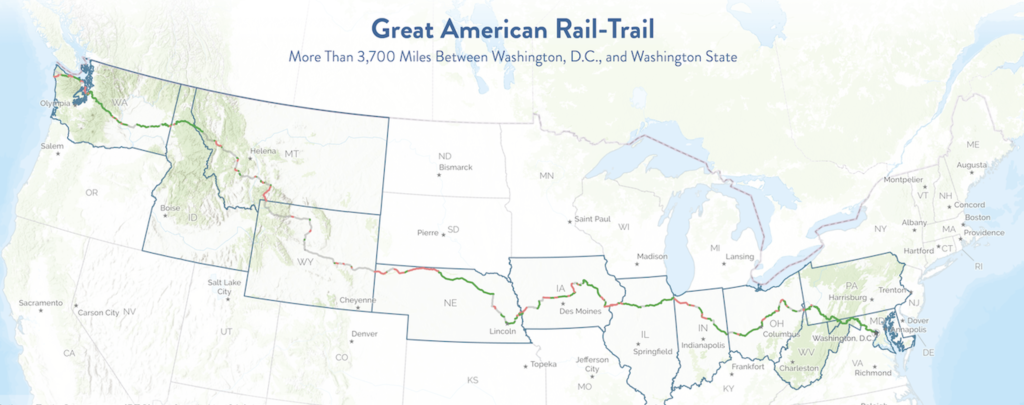

America’s first traffic-protected, coast-to-coast biking and hiking trail will link both sides of the North American continent with an uninterrupted pathway extending 3,700 miles across 12 states and the District of Columbia.

More than half of the pathway was already finished when the Rails to Trails Conservancy (RTC) launched the Great American Rail Trail project two years ago. That’s because a major percentage of the existing trail system consists of abandoned railroad corridors where tracks have been removed and the right of way covered by pavement or crushed stone. These existing trails are currently available to be ridden by the public.

Supported with $18,400,000 in public and private financing, the RTC completed an additional 50 miles in 2020 completing just over 53% of the route.

Despite the progress made over the past few years, more than 95 gaps totaling around 1,700 miles remain as the project is expected to take over a decade to complete. Most of the gaps exist in Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska which lack existing railroad rights of way. The Conservancy is working to solve the problem by looking for financing to advance specific state priorities. Many of the existing gaps in Montana will soon close thanks to fast track funding from Montana officials. “The Paradise Valley in Montana is the northern entrance to Yellowstone National Park, a major draw for people heading down the trail from Livingston,” says RTC Manager of Trail Planning Kevin Belanger. “That corridor just seems like a no brainer to us for active transportation recreation.”

Segment under construction on the Montour Trail in Pennsylvania | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

Is there really a need for an expensive trail of this magnitude? Yes, says RTC President Ryan Chao, pointing to what has transpired over the past year. “I think that we’ve learned through the pandemic that safe, convenient access to the outdoors isn’t just a fun thing to have. It’s vital for individual mental health and for community wellness.”

The numbers don’t lie. There was a 200% surge in trail usage at the start of the pandemic followed by a 50% increase throughout the entire year of 2020, according to the RTC. Aside from stress relief the trail will also bring economic and environmental benefits.

Most car rides in the US each day are short trips that could be accomplished on a bicycle, notes Chao. If the 50 million people living within 50 miles of the Great American Rail Trail used bicycles more often, vehicular emissions could plummet.

Echoing Chao’s sentiment, RTC Vice President of Communications Brandi Horton says the towns and communities connected by the trail are destined to enjoy very tangible economic benefits. States like Wyoming and Montana whose economies once relied on the railroads, or extractive industries like oil, coal or natural gas, now can augment their economy with revenues from tourism and outdoor recreation. Says Horton: “This trail will be a catalyst to do all of that.”

For example, businesses along the Great Allegheny Passage corridor in Maryland and Pennsylvania are seeing growing portions of their total annual business attributed to the trail, according to the latest Business Survey Report for the Great Allegheny Passage trail. The study concluded that restaurants, campgrounds, hotels and outdoor recreation providers attributed 41% of their total business directly to the trail.

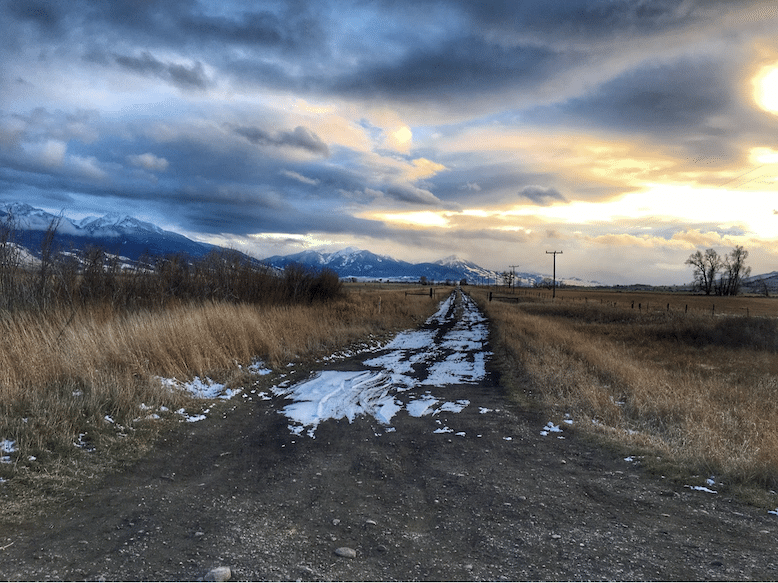

Future Great American Rail Trail in Park County, Montana | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

Because of the numerous benefits the RTC identified, Horton says that states are buying into the ambitious aspirations of the trail and offered Indiana as an example.

“When we went to Indiana, people told us they wanted as many trail miles as they could get,” says Horton, noting the tremendous enthusiasm to show the essential beauty of America. “They worked with us to define a preferred route that would maximize Indiana’s exposure to the Great American Rail Trail.”

These meetings culminated in a trail plan through Indiana that will travel diagonally across the state, aided by a $1 billion infrastructure program that Governor Eric Holcomb announced in September 2018. The planned trail moves from the northwestern border of the state just outside of Gary, and travels 220 miles southeast to Richmond on the Ohio border.

From Olympic National Park in Washington to Cuyahoga Falls National Park in Ohio to the numerous national monuments in Washington DC, the Great American Rail Trail will allow travelers to hike and bike along uniquely authentic byways. The Conservancy highlighted existing “gateway trails” that will allow travelers to capture the essence of every state along the route. “We don’t want this to be an entirely uniform experience because this country is not an entirely uniform place,” says Belanger.

The trails are as follows: Capital Crescent Trail from Silver Spring, MD to Georgetown, DC; C&O Canal Towpath from Cumberland, MD to Georgetown, DC; Panhandle Trail from just west of Pittsburgh, PA to Weirton, WV; Ohio to Erie Trail from Cleveland to Dalton, OH; Cardinal Greenway from Marion to Richmond, IN; Hennepin Canal Parkway from Bureau Junction to Colona, IL; Cedar Valley Nature Trail from Evansdale to Ely, IA; Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail from Norfolk to Valentine, NB; Casper Rail Trail in Casper, WY; Headwaters Trail System from City of Three Forks to Missouri Headwaters State Park, MT; Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes from Mullan to Plummer, ID; and Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail from Smyrna to Cedar Falls, WA.

Extending from the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State 3,700 miles across the country to Washington DC, the Great American Rail Trail is 53% complete. Eighty miles are under construction with more on the way. Segments in green are complete, planned segments are in red and unplanned segments in grey. | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

Chao pinpoints the Ohio to Erie Trail and the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail as notable existing trails that bikers, hikers, and travelers will surely enjoy. “Within a few days we went through pastoral, rural farmland to industrial city and then back into a national park in terms of the Cuyahoga Valley Park just south of Cleveland,” he says. On the Ohio to Erie Trail it’s possible to safely bike across just about all of Ohio. Indeed, with a little planning it’s entirely feasible to ride or walk at a pace you deem comfortable through the state capital of Columbus before rolling onto rural areas that contain Amish settlements. Once rested, it’s easy to peddle east to Akron, the hometown of NBA player LeBron James.

The RTC website points out that travelers on the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail “will experience many landscapes: mountains, dense forests, irrigated farmland, arid scrubland, and the rolling hills of the Palouse region.”

Many of the majestic gateway trails run through or will end up running through what Chao calls “trail towns.” These towns will reap the greatest commercial benefit from people traveling on the trail. In return, they will provide travelers the opportunity to interact with local people from diverse backgrounds.

Cardinal Greenway in Indiana | Photo by Tony Valainis | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

There are towns along the routes that have been there since the dawn of the railroads. Many of them need fresh investment to upgrade bed and breakfasts, restaurants, other tourist amenities. “I rode the Great Allegheny Passage [in 2019] and it was fun to enjoy all the scenery,” says Chao. “But it was just as enjoyable to stop in the towns and get to know people, stay overnight, and just enjoy the local atmosphere.”

Some of the existing trail towns along the Great Allegheny Passage include Meyersdale, PA, where the annual Pennsylvania Maple Festival is held; Ohiopyle, PA, home of the Ohiopyle State Park, and Boston, PA known for Dead Man’s Hollow nature reserve and the blue Boston Bridge.

Horton’s favorite route is a relatively unknown trail in Glen Rock, Wyoming called Al’s Way. It’s named after local track coach Al Finch, who often took his team running along the abandoned railroad line. The community took initiative to turn it into a trail for the track team to have a dedicated space to run. Horton says stories like this are what makes the Great American Rail Trail so special.

Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail in Washington | Photo by Gary Toriello | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

“When you talk about exploring the country from the seat of a bike, or in your sneakers, you’re going to find these personal stories. You’re going to meet the ‘Al’s’ all along the way and hear about their experiences and why they love their community. When all of this work started years ago progress relied on volunteer activism,” Horton says. “A lot of these trails come from people like Al.”

The Great American Rail Trail can be used by people with differing abilities. Since trains don’t travel on steep inclines, the trails lend themselves to relaxing strolls, people in wheelchairs, or those seeking long distance biking. Public trails are known as some of the safest recreational sites as well, so for whatever a person is looking to get out of the trail they will be able to do so in peace. What’s unanimous among Belanger, Horton, and Chao is that this trail will offer the people who use it an entirely different view of America.

“This trail is for the locals, it’s also for those with a [broader] idea of what this cross country trail can be. This trail is a vision, a lifelong goal and a bucket list item,” Belanger says.

Capital Crescent Trail, located in Maryland and Washington DC | Photo by Hung Tran | Courtesy of Rails to Trails Conservancy

Horton pointed to the trail’s historical and cultural significance, mentioning the Raccoon River Valley Trail. Built in the 1870s, it originally was a railroad built to carry passengers and cargo from Iowa to the Great Lakes States. Other trails such as the National Mall Trails in Washington DC take travelers through significant historical landmarks including the Lincoln Memorial, Constitution Gardens, Washington Monument, and Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site– a road rich in history from presidential inauguration parades to the Women’s Suffrage Procession in 1913.

“It’ll be incredible to go from the east coast where you have deep revolutionary history to the Midwest and Iowa, where the Raccoon River Valley Trail takes bikers through incredible farmland. And then as you move to the Mountain West you’ll see and experience different geographies and cultures of the United States,” Horton says.

“[The Great American Rail Trail] spans pristine forests, preserved public lands, rural areas, big cities and small towns. But the real benefit is that you experience everything more intimately by walking and biking,” says Chao. “When you slow down you see things differently and achieve a more meaningful connection with the environment.”![]()

Alex Eisman is an Ann Arbor, Michigan native majoring in Broadcast and Digital Journalism with a minor in Sport Management at Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications.