Goreme’s residents live in homes with all the modern amenities. But from the outside, Cappadocia’s “modern” neighborhoods still reflect the area’s colorful past. Photo by David DeVoss

Today’s visitors to Turkiye’s Cappadocia, a three-hour drive from Ankara or a 75-minute flight from Istanbul, come for two reasons – spectacular sunrise ascents over the rugged terrain in hot air balloons and stooped-over descents underground into retreats that protected residents, their livestock and possessions from ancient visitors who were far less friendly.

These hand-dug hideouts were elaborately engineered, multi-layered warrens of tunnels and rooms, some of which reached more than 275 feet into the earth. Among the people who hunkered down in them were early converts to Christianity when the faith was spreading across Asia Minor.

The existential threats in the early centuries following Jesus’ resurrection came not only from Roman governors and Jews but also from followers of different ideologies traveling on the Silk Road that passed through Cappadocia. Disputes could be doctrinal, territorial, or simply monetary. Regardless, the early Christians were far from the first to hide underground here.

Between 150 and 200 ancient underground cities lurk beneath the Cappadocian landscape, according to Turkiye’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism. They differ in size, but the largest could accommodate more than 20,000 people. Connecting tunnels linked some communities, permitting people to disappear in one spot and emerge miles away.

Life Below Ground

Elengubu, now called Derinkuyu, is one of the three most visited underground cities (the other two are Kaymakli and Ozkonak), and its scale is amazing. It has 18 interlocking tunnel levels that reach 275 feet under the dusty surface. The culture and tourism ministry operates the nation’s underground cities and has prepared Derinkuyu’s top four levels for visitors. Electric lights shine brighter than the original users’ linseed oil lamps, and directional signs keep visitors from wandering off into dusty dead ends.

Sometimes, a visitor to one of Cappadocia’s hidden cities must climb up before he can walk down. Photo by David DeVoss

Archaeologists and historians believe that the Hittites began excavating Derinkuyu around 1200 BCE. They needed protection from invading Phrygians, who perhaps originated in northwestern Anatolia or as far away as modern Bulgaria, Romania, North Macedonia and northern Greece. Earlier residents of this part of Asia Minor had occupied and probably expanded natural caves that dot the region’s steep canyon walls.

My guide through the underground city of Kaymakli explained how the area’s geology permitted the construction of the intricate complexes. Millions of years ago, volcanoes spewed layer upon layer of ash. Lakes formed and then evaporated. More ash fell. Compression and the passage of time transformed the ash to a porous rock called tuff that is soft enough to be excavated with simple tools such as picks and shovels.

Thank God For Cow Livers

Some small interior tunnels must be traversed in a crouch. A few on inclines are best negotiated while seated as if they were slides on a children’s playground. Photo by Jennifer Broome

The same volcanic and geologic action – plus an overlay of harder igneous rock – created another of Cappadocia’s attractions called fairy chimneys. These are spires of tuff capped with harder, cone-shaped rock that demonstrate the capricious effects of erosion. The phallic fairy chimneys are notable features of the Goreme Open Air Museum near Kaymakli and Derinkuyu.

The builders’ underground engineering prowess is obvious. Vertical ventilation shafts delivered breathable air. Cutouts between levels permitted communication. Access tunnels still feature half-ton boulders resembling the stones of a gristmill positioned vertically so they could be rolled shut inside to block any attackers. Small shafts entered some rooms at ceiling level so hot oil could be dropped on intruders who did manage to enter. In some ways, it appears that the creators of Raiders of the Lost Ark took some ideas from the ancient Cappadocians.

Tourists to Cappadocia at the Goreme Open Air Museum walk past Fairy Chimneys. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Since horses, cattle and sheep went underground too, the aromatic question of waste disposal arises. Author Chris Fitch in a book about underground spaces titled Subterranea, offers this tidbit: “By adding lime to cow livers, residents devised a method for speeding up the decomposition of organic waste, enabling them to dispose of the immense quantities of human and animal excrement that would otherwise overrun the tunnels.”

Christians Expand Older Excavations

Tourism promotion for the underground cities puts much focus on early Christians and their persecution in the first centuries after Christ.

“There are scads of traditions that insist apostles Peter and Paul founded churches in Cappadocia, but there is no way to verify that historically (meaning there is no documentation from that era),” says Bob Ratcliff, a retired editor of theological books and teacher at Emory University in Atlanta and Belmont University in Nashville, Tenn. However, there is an account in Chapter Two of the Acts of the Apostles of Peter meeting in Jerusalem with Christians from Cappadocia shortly after the resurrection of Jesus.

Christianity did spread rapidly, and by the 4th century AD, Ratcliff says Asia Minor had the highest concentration of Christians in the Roman Empire. In some places, Christians were the majority. Constantine became the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire in 312 and established Constantinople, now Istanbul, in 330.

Worthy of note is the fact that 2025 is the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea (today’s Iznik), a gathering Constantine organized for approximately 300 bishops from throughout the empire. One outcome was the Nicene Creed, a profession of faith still is use.)

According to Ratcliff, the Roman Empire persecuted Christians as a matter of policy only twice. “Those were in 247 and 303 AD, and both lasted for only a couple of years,” he says, noting that Cappadocian Christians faced other threats on an ongoing basis, regardless of their faith.

A round stone door weighing half a ton could be rolled shut from the inside to prevent intruders from entering the underground city. Photo by Jennifer Broome

Early Cappadocian Christians expanded the underground cities, and the region became a place of sanctuary and development of Christian doctrine. Early theological thinkers found relative safety here. Ratcliff particularly points to three church fathers and one often overlooked church mother – Macrina, her brothers Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa, and the brothers’ friend, Gregory of Nazianzus – as important Cappadocian figures.

Whether as hiding places or storage spaces in more recent centuries, the underground cities remained in use until 1923, when Turkiye and Greece forced two million people to uproot from their ancestral homes in what was called “a population exchange.” The underground cities seemed to disappear from the collective conscience until 1963 when, as the local story goes, a resident expanding his above-ground house in the village of Goreme broke through a wall and entered another realm. It was a “Twilight Zone” moment.

Christians living in underground cities like Derinkuyu, Kaymakli and Ozkonak in the first and second centuries AD worshipped in chapels such as this. Photo by David DeVoss

‘Discovery’ leads to Tourism

Scores of other underground cities came to light, and the Derinkuyu underground city opened for tours in 1965, according to the Culture and Tourism Ministry. The ministry reported combined visitation at Derinkuyu and Kaymakli to be 1.1 million in 2024.

As the value of underground cities’ tourism became clear, so did the importance of the region’s array of at least 60 ancient Christian churches in the Goreme Valley. Many were built around the year 1000, and the most visited are in the Goreme Open Air Museum, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The museum’s walkways, some fairly steep, lead up the sides of tuff valleys to innocuous church entrances. Inside several of them are brilliantly colored murals of saints and biblical scenes that are the payoff to those willing to climb just a bit.

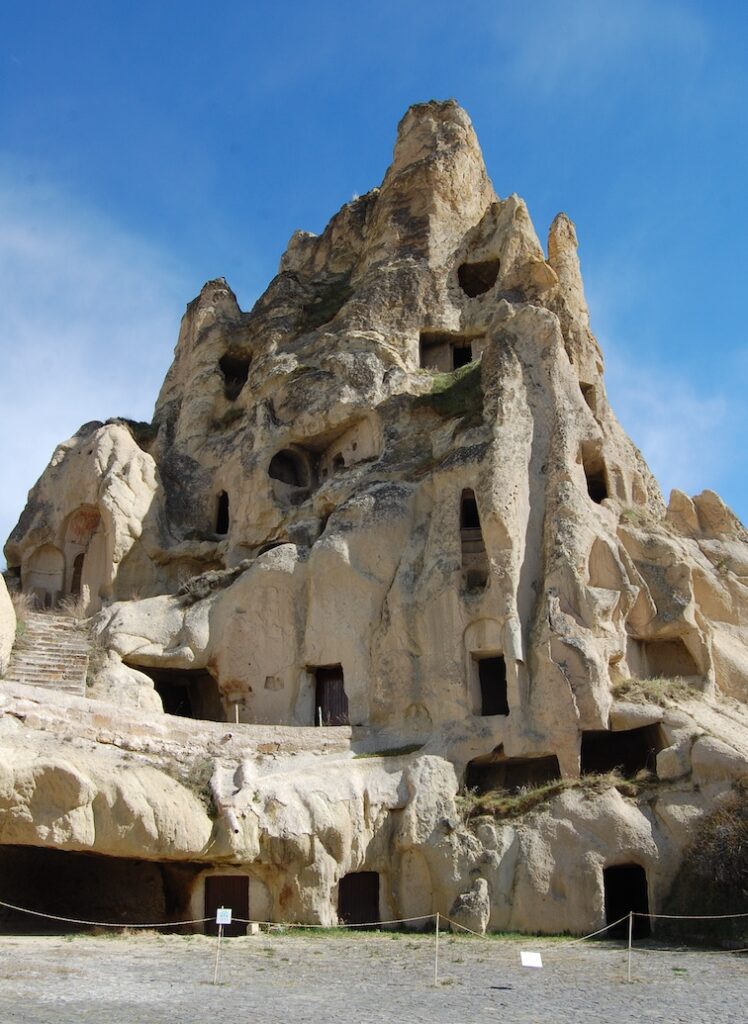

Most hand-hewn apartments in this tufa “highrise” were inhabited well into the 20th century. Today, ground-level enclosures are used to park cars. Those higher up are used as storage units. Photo by David DeVoss

After the underground cities and the historic churches drew international attention, Goreme grew from a rural village tucked into Cappadocian hillsides to a visitor-oriented destination. A “cottage industry” – a cave industry, really – evolved. Residents and developers transformed tufa escarpments into thoroughly modern hotels with all the expected comforts and amenities. The culture and tourism ministry reports that around 850 cave hotels have opened since the early 2000s. Their designs incorporate the adaptive use of genuine cave real estate or take their architectural cues from the Anatolian terrain.

They range from traditional accommodations to boutique properties and even to high-end luxury resorts. The culture and tourism ministry says the first luxury property was the Museum Hotel in Nevsehir. Another example in Uchisar is named the Argos in Cappadocia. Regardless of the price point, guests don’t have to stoop through narrow tunnels or pass by rolling stone security doors.

Dining Room in Cappadocia’s Argos Hotel. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Soaring Above Hidden Cities

Beyond the cave hotels, underground cities and churches, yet another attraction enhances Cappadocia’s popularity – flights over the countryside in hot air balloons.

“Cool and calm mornings here make it possible to fly throughout the year. For my company, that’s around 250 days a year,” said Tolga Eke, flight operations manager at Royal Balloon, one of 21 companies in Cappadocia that together stage dawn launches of up to 150 balloons. Their baskets carry up to 28 passengers.

On those calm mornings, the roar of propane burners inflating 65-foot-tall balloons cuts through the pre-dawn darkness as vans deliver passengers from Goreme, Nevsehir and other towns. The liftoff is from a maze of narrow valleys. The tan and gray landscape looks lunar, but it is deceptively fertile. Vineyards and agricultural fields appear in the growing daylight.

My flight rose to 7,500 feet to watch the sunrise over the horizon, but the most fun came closer to the ground. We glided past fairy chimneys and floated almost at eye level with people on rooftop terraces in Goreme, practically close enough for them to hand off their cup of Turkish coffee.

Hot air balloons preparing to take off on early morning flights over Cappadocia. Photo by Tom Adkinson

While aloft, I tried to imagine the ancient civilizations that occupied the landscape below, scratching their existences from the arid dirt and always wondering when they would have to beat a retreat into their underground sanctuaries.

EWNS contributing writer Tom Adkinson has experienced Cappadocia in a hot air balloon and in the tunnels of an underground city. His other EWNS stories include ones about the man who taught Jack Daniel how to make whiskey and Charleston’s International African American Museum.