By John Gottberg Anderson

Angkor is a city that haunts the imagination. For those of us who knew of its mysteries before it was discovered by Hollywood, Cambodia’s crown jewel is one of those rare world destinations — like Peru’s Machu Picchu or the pyramids of Egypt — that forever commands our wanderlust.

From the start of the 9th century to the early 15th, Angkor (a name that means “city”) was the capital of the Khmer empire. It is said to have been larger than modern Paris, home to several hundred thousand people, supported by a remarkable system of canals and reservoirs. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it sprawls across about 75 square miles of forest and farmland.

Upon this landscape stand six dozen major temples and several hundred minor temples. Iconic Angkor Wat (“city temple”), perhaps the world’s single largest religious monument (alternately representing both Hinduism and Buddhism), was built in the first half of the 12th century. The fortified Angkor Thom complex, 3 kilometers square, was constructed later in the 12th century just north of Angkor Wat.

After the Siamese captured Angkor in 1431, the capital was abandoned — save for Angkor Wat itself, which continued to be revered as a spiritual site. The ruins were briefly rediscovered by Portuguese missionaries in the late 16th century and by Japanese immigrants in the 17th. Mostly, though, Angkor was swallowed by the forest. Not until the mid-1800s, when French priests and scientists arrived in Cambodia at the vanguard of colonialism, did the ancient city arouse any kind of interest elsewhere in the world.

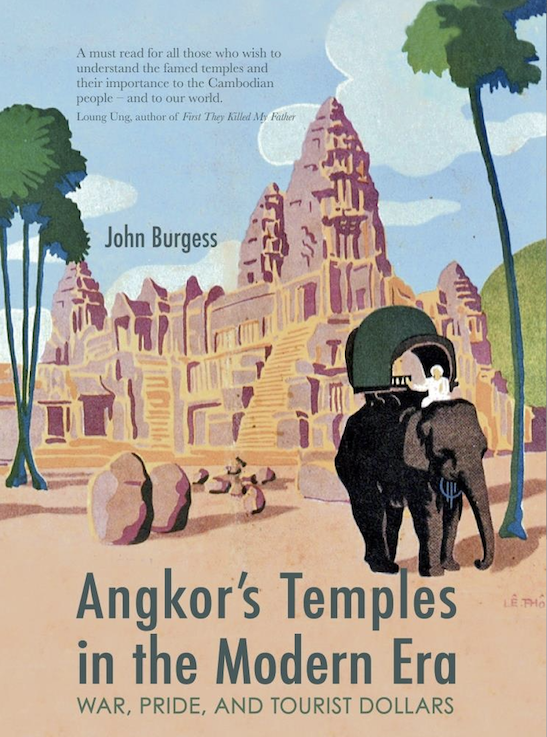

Angkor’s Temples in the Modern Era:

War, Pride and Tourist Dollars

John Burgess

ISBN: 978-6164510463

Author John Burgess begins his exploration of modern Angkor with an acknowledgement that although Angkor’s ancient history has been extensively studied, its modern tribulations are often conveniently ignored. And in the years between 1860 and 2020, there have been trials galore — remarkable conservation work, of course, but also government corruption, massive theft, war and outright brutality. Through it all, Angkor has been Cambodia’s citadel. It is a symbol of the nation that appears on its flag, its currency, its postage stamps.

As an American with deep experience in Southeast Asia, Burgess has written four previous books about Angkor, including two novels and two nonfiction works. But this may be his most personally felt account. A variety of sidebars and a fine selection of art, from historic prints to the author’s own photographs, support a breezy book design.

Scheduled for U.S. release on April 21, 2021, the book begins with the first foreigners who helped to introduce Angkor to the West — young French Catholic priest Charles-Émile Bouillevaux, who visited in 1850, and scientist Henri Mouhot, who spent two weeks at Angkor in 1860 and dubbed the ruins superior to “all the art that the Greeks or Romans ever built.” His journals, published in 1863, ignited a flame of interest in Europe. Others followed, visiting Angkor by elephant or oxcart; their descriptions, drawings and photographs furthered European curiosity.

Archaeologist Louis Delaporte conducted the first detailed survey of Angkor in the 1870s. After eight years in Asia, he returned to France in 1881 with 27 oxcarts full of stolen sculptures for European museums. His mission, along with Mouhot’s diary, enabled France to rationalize its colonization of Cambodia — to glorify its past while enforcing the “civilizing” influence of modern Europe.

Angkor Wat as depicted in an image detail from the first publication of Henri Mouhot’s journal, in Le Tour du Monde (1863). Photo from Bibliothèque Nationale de France. (page 9 of book)

At the end of the 19th century, the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), or “French School of the Far East,” took a lead role at Angkor. In its mission of clearing the monument of overgrowth and recovering sculptures, the Saigon-based research institute stumbled upon one of the fundamental conflicts between the well-meaning French and cultural heritage: Many families (farmers, fishers, market vendors) were uprooted in the name of preservation.

One of my favorite parts of Angkor’s Temples in the Modern Era is the description of work by late 19th-century linguists who deciphered and transcribed stone inscriptions in ancient Khmer, Cham and Sanskrit. These laid the foundation for rediscovering a long-lost history. The story was, in fact, the subject of a previous Burgess book, Stories in Stone.

Beguiled by the romance of the ruins, the French nonetheless struggled with an urge to rebuild them. Should they merely administer palliative care, or make a greater effort to reconstruct the monuments as they perceived it had once looked? There was also spiritual tradition to consider — to the enlightened, Angkor was a supernatural realm, best not disturbed.

That didn’t stop adventurous tourists, including travel writers, from seeking it out. As early as 1872, when women rarely journeyed solo, British writer Theresa Yelverton visited Angkor and wrote about her 12-day stay for The Overland Monthly, whose other contributors included Mark Twain and Jack London. To accommodate new arrivals, a 10-room guest house, The Bungalow, opened in 1909 beside the temple’s western moat. By the 1930s, the place was renamed Hôtel des Ruines and enlarged to 21 rooms with white linens and intermittent electricity. Even then, well-to-do travelers felt entitled to complain about the “primitive ordeal” of their experience. That improved in 1932 with the opening of an airport and a major new hotel in Siem Reap, the gateway town, 5 kilometers distant.

The 20th-century history of Angkor was mostly about war … and Norodom Sihanouk (1922-2012). Only 19 years old when he assumed the Cambodian throne in 1941, he became — as Burgess describes him — “a seminal, willful figure in the country’s modern history as well as Angkor’s,” trading domestic and international alliances as he found politically expedient. He even staked his claim to fame as a filmmaker, producing at least six movies in the late 1960s as director, screenwriter and actor. Angkor was his favorite filming location. As an elder statesman in the 1990s, he worked with UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) in its preservation efforts.

My greatest disappointment in reading this book was Burgess’s failure to flush out the personalities of many of the major characters instead of merely recounting their accomplishments. Sihanouk was a fascinating individual and I now find myself craving a good biography. Angkor’s Temples in the Modern Era is meticulous in its recounting of the ancient city’s last century and a half, and the level of research that went into the project is remarkable. But it occasionally reads like a textbook, without the soul that a sometime-novelist might have injected.

Angkor remained safe from warfare through World War Two and the Vietnam War. Japanese troops stationed at Siem Reap between 1941 and 1945 were never attacked. When the American war in Vietnam began spilling into eastern Cambodia in the 1960s, Angkor remained distant and Sihanouk began promoting tourism there. Indeed, at the peak of the Vietnam War, about 50,000 foreigners a year were visiting the ruins, and a new generation of Cambodians earned livelihoods as guides, cooks, drivers, elephant keepers, conservation workers and vendors.

The flamboyant and unflappable Prince Norodom Sihanouk poses in front of Angkor Wat in a 1973 visit. Photo courtesy of Documentary Center of Cambodia Archives. (page 181 of book)

The blessed isolation changed with the emergence of the Khmer Rouge, a homegrown insurgency movement that allied itself with the North Vietnamese. Angkor’s darkest decade began when Vietnam sent an occupational force in 1970 and the monument became a refuge for thousands of ordinary Cambodians. Military attacks destroyed The Bungalow and damaged temple walls and sculptures. After the U.S.-backed Lon Nol administration collapsed in April 1975, the Khmer Rouge flew an image of Angkor on their flag to exalt their glorious past and heroic future. But this was “The Killing Fields” era. Mass executions eliminated anyone sympathetic to the old regime. Others, including conservation workers, were forced to labor in fields and live in poorly supplied communes. Bats and tropical foliage moved back into the temples.

After the Khmer Rouge were driven from power in 1979, preservation workers returned. Burgess himself was invited as a journalist for two weeks in April 1980: “Angkor was again a home, not just a heritage site,” he noted. But the pillaging of artifacts, which had abated in the late 1970s, remained evident.

Two years after the final Vietnamese troops pulled out of Cambodia, UNESCO declared Angkor a World Heritage Site in December 1992. Today China is at the forefront of reconstruction work. Aerial mapping and computer imaging helped chart the location of former residences, canals and reservoirs, leading to a greater understanding of size and population as one of the great world cities of the pre-industrial era.

In three decades, Siem Reap has emerged as a classic Asian tourist town. Construction is seemingly nonstop. “The noise and diesel fumes that can appall foreign visitors are to many Siem Reap residents welcome signs of peace and prosperity,” Burgess writes. Tourists can view the temples from the city’s 85-meter-tall Ferris wheel, the Angkor Eye, or take a sunrise hot-air balloon ride over Angkor Wat, avoiding the throngs who fight for photos in the pre-dawn light. Foreign hotel chains include Raffles’ Grand Hotel d’ Angkor and the ultra-luxury Amansara (in Sihanouk’s former villa). There are also museums, international cuisine, classical dance shows and a gaudy Pub Street. A new Siem Reap International Airport is being built 28 miles (45 kilometers) southeast of the city. Tour guides are fluent in Khmer culture and a great many foreign languages.

Annual tourism numbers climbed from 200,000 in 2001 to more than 2 million in 2013. They maintained that level until the arrival of the coronavirus in early 2020. As Burgess notes in a postscript, it will be hard to forecast post-COVID-19 numbers. Until a spike in new cases in March and April 2021 (including the nation’s first recorded deaths), Cambodia had impressively staved off the virus. But other countries have not, and it is unlikely foreign tourists will be widely welcomed until the disease is under better control.

Annual tourism numbers climbed from 200,000 in 2001 to more than 2 million in 2013. They maintained that level until the arrival of the coronavirus in early 2020. As Burgess notes in a postscript, it will be hard to forecast post-COVID-19 numbers. Until a spike in new cases in March and April 2021 (including the nation’s first recorded deaths), Cambodia had impressively staved off the virus. But other countries have not, and it is unlikely foreign tourists will be widely welcomed until the disease is under better control.

When widespread tourism returns to Angkor, it will again be embraced as a boon to the economy, bringing hope for financial stability, education and general advancement. It also will bring new challenges for the temples’ physical and spiritual integrity, along with the region’s water resources. As Burgess suggests, the COVID years finally may offer Angkor the opportunity to reconsider how it manages tourism and conservation efforts.![]()

John Gottberg Anderson is former editor for The Los Angeles Times, France’s Michelin Guides and the Singapore-based Insight Guides. He lives in Vietnam and writes a blog, www.travelsinvietnam.com.