The Greatest Show on Earth may be the Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, as seen from the hills around Dawson during the winter.

I’m sitting in the Sourdough Saloon at the Downtown Hotel, in Dawson City, Yukon, about to drink neat gin containing a preserved human toe!

No, I haven’t stumbled into a crazy community of cannibals. But, perhaps crazy isn’t an entirely unapt description of a town that not only embraces the Sourtoe Cocktail, but also offers a Dog Ball High Ball (ingredients obvious) each year in March. This canine cocktail (key component courtesy of the local vet) celebrates the beginning of the spring thaw and is sold to raise funds for – you guessed it – the Yukon Humane Society.

The original toe belonged to Louis Linken, a prospector who lost it to frostbite. He dropped his toe into a bottle of rum to preserve it and then promptly forgot the lost appendage. When the next owner of the cabin found the bottle his friends bet him he wouldn’t drink a cocktail with the toe as garnish. Of course, he did, and the Sourtoe Cocktail was born.

So why would I swallow this drink with its unappetizing contents? Why, to prove that I’m not a Cheechako (incomer to the Yukon) but have the grit to be a real sourdough (Yukoner). And believe me, those first Yukoners, who largely subsisted on sourdough bread, had grit.

Paying $5 to plop a desiccated human toe into a $5 glass of alcohol at the Sourdough Saloon seems like a fun thing to do. But the toe has to touch the imbiber’s lips before sourdough status is conferred.

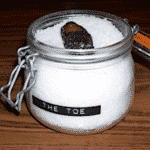

My $5 glass of gin in hand, I approach the keeper of the toe, sitting at a nearby table. The gristly appendage rests on a bed of salt, and for another $5, he indecorously plops it into my glass. The other customers gleefully watch carefully to ensure that I slug down the gin. They chant, “Slug it down!” You see, the toe must touch my lips.

What’s a Sourtoe Cocktail like? Frankly, the neat gin is far more distasteful than the toe, which does, indeed, touch my lips. Yes, I am a sourdough!

The toe used for Sourtoe Cocktails is preserved in salt

But consider this, as of summer’s end, more than 89,000 people had paid $5 each to add the toe to their drink. There’s more than one way to strike gold in the Yukon. And gold is, after all, what created Dawson City.

The story of Dawson begins in 1896, when George Carmack and his wife Kate found the first gold nuggets, sparking the Klondike Gold Rush. Hardy prospectors flocked in, most trekking from Skagway, Alaska along the gruelling Chilkoot Trail, a 33-mile route through the Coast Mountains. By 1898, Dawson City boasted a population of nearly 40,000; it was even known as “The Paris of the North”.

But there’s always been ‘more flannel than Chanel’ in Dawson – both actually and metaphorically. Prosperity didn’t last long, and while most left with empty pockets, a resilient, few remained.

Now, more than a century later, the population numbers fewer than 2,000 during the winter. That’s when the thermometer dips below -30C, and the sky remains stubbornly dark for most of the day. Who are these hardy sourdoughs?

Jackie Olson is a Dawson artist who draws on her indigenous roots and elements of the land – feathers, quills, beads and handmade fibres – to create imaginative 2- and 3-dimensional dioramas. “After busy summers, most of us roll up the carpet for a while,” she says. “But we don’t hibernate for long. There are festivals and events all winter so there’s no chance of cabin fever.”

Dawson artist Jackie Olson enjoy’s the long Yukon winters because of the community camaraderie and the opportunity to get work done.

Olson describes a remarkable community that comes together for music, hockey tournaments, skating, skidoo races – and festivals. The annual winter arts festival – called “(s)Hiver” – celebrates the coldest time of the year (hiver in French).

In February, “Trek Over the Top” brings American snowmobilers from Tok, Alaska over 200 miles of wilderness trail to join in a weekend of fun in Dawson. And in March, Thaw Di Gras replaces Mardi Gras as Dawson’s unique winter carnival. Events include smoosh racing (four team members strapped to a pair of 2 X 4 boards), snowshoe baseball, tricycle racing, and even human curling (instead of a kettle-shaped rock, a team member is pushed down the ice).

The Thaw Di Gras Spring Festival features smoosh racing and other events not yet recognized by the IOC.

“We get visitors from Australia and Asia, and even Mexico in the winter, because they want to experience the real Dawson,” Olson says. Of course, they come for the skiing, the dogsledding, and the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights), but she adds, “They come for the community. They talk to the local characters in the bars, or gossip with the tea ladies who meet at the Downtown Restaurant in the afternoon.”

In fact, getting to know the people seems to make visitors want to stay. Jesse Cooke came here 15 years ago “for the adventure of it.” He never left. “It’s a place where creativity flourishes, and living an alternative lifestyle doesn’t place you on the fringe of society,” he says. “There are so many people here, doing so many different things.”

Cooke lives off the grid with his family across the Yukon River in West Dawson. He runs The Klondike Experience, a tour business. His year-round tours might include a chance to meet local characters who have great stories to tell, or a late night ride into the woods to enjoy coffee round a campfire and watch the magical Northern Lights.

Everyone feels like a winner at the Thaw Di Gras Tricycle Races at The Pit.

Here comes the sun

Summer changes more than the landscape. The sun sets only briefly each night, and seasonal staff and tourists quadruple the population. But Cooke is quick to add, “We aren’t a fake Northern town created for tourists. This is an authentic community. First Nations people lived here for thousands of years before the Gold Rush. Artists and adventurers and free spirits have trickled in. We all live and work together. That’s what makes Dawson unique.”

Dawson City packs a much larger creative punch than one might expect from a town of its size. Seen from the Midnight Dome, a lookout above the town which offers breathtaking views of the Yukon River and the Ogilvie Mountain range in the distance, the town of Dawson below is tiny. It is, in fact, just 11 city blocks by eight and looks as if it could have been lifted straight out of the set of a Hollywood western.

At midnight, as I walk back to the Eldorado Hotel, the sun is just starting to drop, casting a warm glow on the weathered wooden buildings, many unchanged for more than 100 years. On the wooden sidewalks, even sneaker-wearing pedestrians sound like approaching zombies. The scene cries out for John Wayne, striding along the dusty street. But this isn’t the American west. Pierre Berton, one of Canada’s most prolific writers who was born in the Yukon, probably explains the difference most succinctly: “Barroom shoot-outs and duels in the sun have no part in our tradition. We have too few barrooms and too little sun. It is awkward to draw for a six-gun while wearing a parka and two pairs of mittens.”

The best view of Dawson, the Yukon River and the Ogilvie Mountains in the distance is from Midnight Dome high above the city.

With daylight still bright on this late night in August, I’m having a hard time telling myself it’s bedtime. So, instead, I stop into Diamond Tooth Gertie’s for a last drink. The Gold Rush style cabaret is in full swing with a steady clatter coming from the roulette and craps tables. Gertie’s, the first and still only casino in Northern Canada, is named for Gertie Lovejoy, a famous 19th Century dance hall queen. Her nickname is apt; she actually had a real diamond implanted in her tooth.

As one might expect in a town where most of the inhabitants were men, Dawson’s early history is littered with dance halls and brothels. Many working women opened what became known as Cigar Stores. These stores – a row of small houses – still stand in aptly named Paradise Alley. The protocol then was simple: if the blind was up, the customer was welcome to enter and ‘buy a cigar’.

Larger “guest houses” were run by characters like Ruby Scott and Bombay Peggy. Today, Bombay Peggy’s is an elegant Victorian inn with adjacent pub, which has hosted celebrities like Steve Martin and Jack Black.

With a population that fluctuates between 2,000 and 8,000 people depending on the season, Dawson has most of the comforts of a modern city. It’s still waiting for traffic and a rush hour.

It wasn’t until 1962 that Ruby Scott’s brothel – a classic piece of Dawson architecture – finally ceased trade. By then, the good madam had actually become a pillar of the community! Generous to a fault, she supported every charity and good cause, and for good measure, she was known to ‘ring the bell’ whenever she went to the local watering hole.

Ringing the large prominent bell at the Downtown Bar – a signal that the ringer is buying a round for everyone in the bar – is still a Dawson tradition. And it can prove expensive as one hapless visitor discovered when, unaware of its significance, he rang the bell for fun. “The place was nearly empty,” the unfortunate Guy Poitier, lamented. “Suddenly there were dozens of people in the bar demanding their free drink!”

This isn’t surprising; the bell rings loudly enough for the players in the pool hall next door to hear it. It’s a cautionary tale. Never ring the bell in Dawson unless you’ve deep pockets.

Dawson locals break for a smoke outside the Downtown Hotel. Of course, they may be waiting for somebody to ring the bell at the Sourdough Saloon inside.

Find Your Muse

There’s more to Dawson than brothels and bars. This city has always attracted creative people – writers, artists, musicians, and photographers seem to find inspiration in this rugged, tranquil terrain. Indeed, Pierre Berton’s childhood home annually hosts a four-month long Writer’s Retreat program for Canadian writers.

Jack London came here in 1897 and his books, The Call of the Wild and its sequel, White Fang, are set in the Yukon, long passages evoking the magnetism of the ancient forests. London’s original wilderness cabin outside Dawson was dismantled and a replica constructed in town, with half the wood from the original. It’s a museum today. The other half went to Oakland, California, where a similar structure sits in Jack London Square.

Probably no one brings this region to life more vividly than Robert Service, the Bard of the Yukon. A must is a visit to the two-room cabin he once inhabited. Sitting in his rustic wooden chair on the front porch, I open a book of his poetry and read poems which sing the praises of this austere landscape and the larger-than-life characters who inhabited it. How cold is Dawson in winter? One colorful accounting is the epic poem The Cremation of Sam McGee by Robert Service.

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

Dawson is also a Mecca for aspiring artists and musicians. A visual arts college, the Yukon School of Visual Arts, as well as the Klondike Institute for Arts and Culture, offer artist in residence programmes bringing creative men and women to the Yukon to find their muse. And the city also hosts a summer arts festival. The Riverside Arts Festival in August offers exhibitions, workshops, lectures, public art, live music, and an art market with artists practicing traditional and non-traditional contemporary art from the Yukon and abroad.

Indeed, summer has its share of events. The annual Dawson City Music Festival in July is the Yukon’s oldest. Since 1979, it has hosted performers from around the world in Minto Park, and at the venerable Palace Grand Theatre.

When it opened in 1899, the Palace Grand Theatre was an extraordinary addition to a frontier town. Partly luxurious European-style opera house and mostly boomtown dance hall, it was built by Arizona Charlie Meadows, a wild west- style showman who arrived during the Gold Rush. The current building was constructed in 1962 as a nearly exact replica of the original which had become unsafe and had to be demolished. Now run by Parks Canada, take one of the entertaining tours through the building. You might get lucky and meet one of the ghosts that are said to haunt it.

By the way, one Dawson festival is now on my bucket list. The annual Great Klondike International Outhouse Race in August features teams of four, dressed in costumes, racing their outhouse (also suitably costumed) along a 5-km course. Only in the Yukon!

The Great Klondike International Outhouse Race in August brings in Sourdoughs from as far away as Beaver Creek and Destruction Bay. Those who fall short have the entire winter to practice.

Strike Gold!

Dawson grew out of the Gold Rush and in the headlong charge to find the precious metal, individual prospectors soon gave way to machines. It’s worth a visit to Dredge No. 4. I’m in awe as I look up at this huge gold digging machine whose giant buckets devoured miles of rivers, spitting out the gravel and stones, and forever altering the landscape. Built for the Canadian Klondike Mining Company in 1912, this was the largest wooden-hulled bucket dredge in North America. I’m told that on particularly successful day, it sucked up 800 ounces of gold!

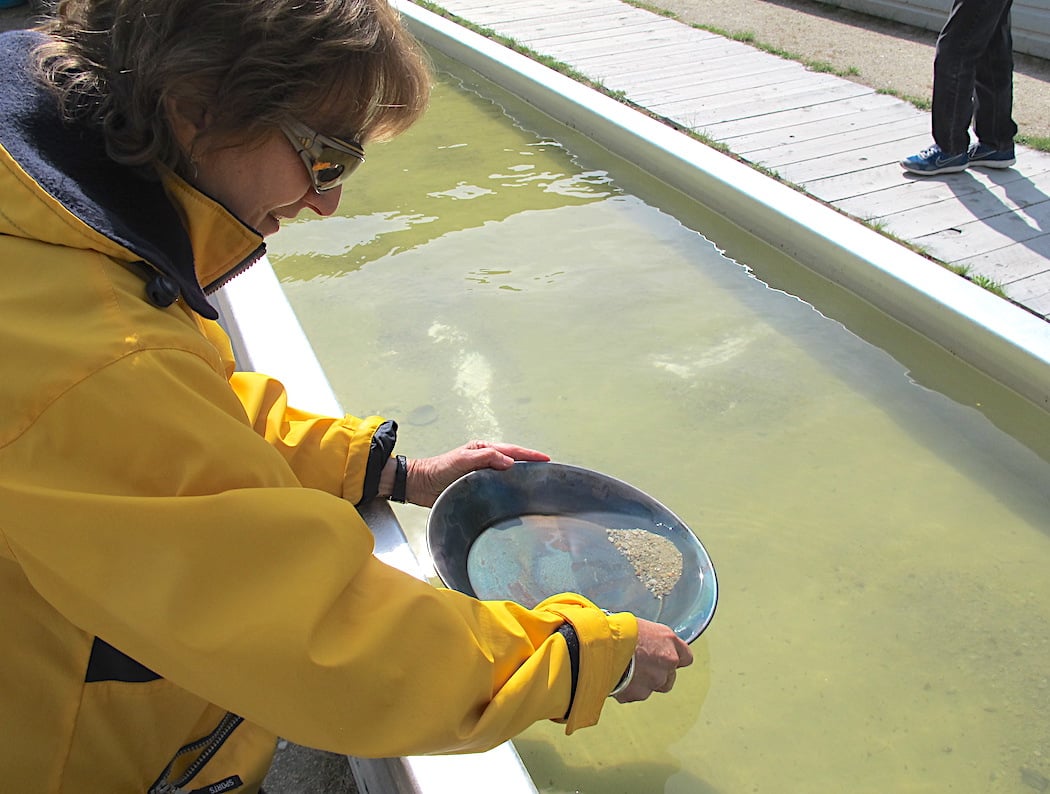

It’s hard to visualize all this fervour and not at least try to find little gold myself. At Bonanza Creek I look hard but alas, none of the pebbles are sparkling. So I head to Claim 33 Gold panning and Jerry Bryde Klondyke Mining Museum, a small family owned and operated business located in the heart of the Klondike gold fields. Here I get clear instructions on how to pan for gold myself – there really is technique involved in doing this successfully.

No trip to Dawson is complete without panning for gold at Claim 33 and the Klondyke Mining Museum. You’re unlikely to strike it rich but you may find gold – if you have the correct panning technique.

I do indeed find gold! Okay, just a few tiny crumbs but it’s thrilling nonetheless. By the way, the company guarantees you will find gold. Make of this what you will, but I’m putting my strike down to efficient panning technique.

Why are shiny stones so important?

If you have time try to visit the Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre to learn more about the heritage of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, a First Nations (Native American) people who have lived around the mouth of the Klondike River for centuries. The Cultural Centre arose from the desire to explain the history of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in apart from that of the Gold Rush sourdoughs.

Interestingly, this is the only building in Dawson which doesn’t meet the by-law requiring buildings to conform to Klondike era structures. Instead its wooden spines rising gracefully in a circle are reminiscent of salmon drying racks and traditional winter shelters.

Displays, films and live performances provide insight into First Nations history and contemporary life. The Gold Rush clearly bewildered them. Caribou and other game were driven away, impacting their way of life, and for what? As one guide put it, “Why were these shiny stones so important?”

Visitors are invited to relax in the rocking chair on the porch of the old cabin where poet Robert Service once lived.

While those important shiny stones built Dawson, the real gold is in the people who live here. Dawson City has a timeless otherness that almost makes it seem like a Yukon Brigadoon. There certainly is nothing ordinary about its people and this special Northern city where they live. Which begs the question: Are you extraordinary? Do you travel to distinctive locales peopled with unique characters? Then do yourself a favour and head north to get to know a few of them living in the Yukon city of Dawson.

Maybe you’ll end up like Robert Service who fell under The Spell of the Yukon:

No! There’s the land. (Have you seen it?)

It’s the cussedest land that I know,

From the big, dizzy mountains that screen it

To the deep, deathlike valleys below.

Some say God was tired when He made it;

Some say it’s a fine land to shun;

Maybe; but there’s some as would trade it

For no land on earth—and I’m one.![]()

Liz Campbell arrived in Toronto, Canada via Burma (now Myanmar), India, and England. She has been a freelance travel and food writer for more than 20 years with stories published in The Globe & Mail, Zoomer, Foodservice & Hospitality magazine and more.