Outside the capital of Tunis lie the ruins of Carthage, a Phoenecian entrepôt destroyed in 146 BC by the Romans in the Third Punic War.

By Susan McKee

Roman ruins surrounded me as I stood, looking out at the clear blue expanse of the Mediterranean. Yet, I wasn’t anywhere near Rome. I wasn’t even on Italian soil. I was on the south coast of the sea – the north coast of Africa — standing amid the remains of an enormous Roman bath on the site of ancient Carthage.

Now surrounded by upscale suburbs of the capital of Tunisia, filled with boutiques, atmospheric restaurants, elegant town houses, and walled villas, this UNESCO World Heritage Site was the second largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire by the first century AD

I had looked at the map before I set off for Tunisia, and I was surprised to see how small the Mediterranean actually is. There are only about 100 miles of water between Sicily and Tunisia – easy to motor across these days, but sometimes treacherous in ancient times. The seabed is said to be littered with the remains of wrecked Roman transport ships and their cargos of amphorae filled with wine and olive oil.

Now, it’s a mere two-hour hop by jet from Paris to Tunis. It’s simple to see how this small country hugging the seacoast has become popular with European tourists in search of sand and sun.

The Phoenicians, who dominated Mediterranean Sea commerce from their homeland centered where modern Lebanon is now, established Carthage in about 800 BC. Virgil wrote that Aeneas – the mythic founder of Rome – spend time here on his way from the Trojan War. In the third century BC, Hannibal launched his elephant-led invasion of the Roman Empire from his hometown of Carthage.

But it was Rome that eventually triumphed over Carthage, transforming it from enemy lair into one of the most important cities of the empire. The ruins I explored were reminders of imperial power and wealth – the extensive bathing complex (with hot springs, cold water pools and more, spread over 4-1/2 acres) was completed in the second century AD under the direction of the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius.

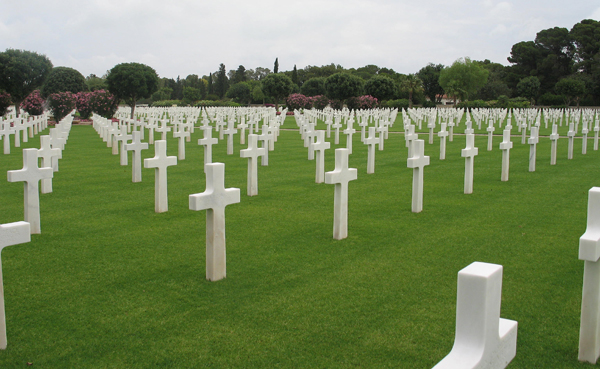

It’s easy to spend time wandering in the Archeological Park, but all of Tunis awaited me. Who knew that there was an American cemetery and memorial in this North African country! Some 2,841 men and women who died during World War II are buried here, and an additional 3,724 of the missing are memorialized. Mosaic tablets tell the story of the fighting in this part of the world.

Colorful plates reflect the color of Tunis’ Arab souk

Historic mosaics also are the stars at Tunis’ Bardo Museum. I spent an afternoon in this former Ottoman palace filled with both Roman and Carthaginian examples ranging from tomb memorials to entire floors constructed from tiny squares of colored stone.

The next day, I headed to the medina (old town), an oval-shaped warren of narrow alleyways packed with all the traditional delights of an Arab souk, including brass tea sets, ceramic tiles, and colorful scarves. Although the city walls that once enclosed it are gone, a few of its iconic gates remain. The oldest, Bab Djedid, was erected about 1276.

All the posh shops are on nearby Avenue Habib Bourguiba, named after the first president of the country, who served from independence in 1956 to 1987. At its northern end, just before the medina, is Place de l’Indépendance, dominated by the massive neo-Romanesque façade of the Cathedral of St.-Vincent-de-Paul. It may seem odd that a Roman Catholic cathedral built in 1882 still serves its congregation, but tolerance is a mantra in Tunisia, long a crossroads of cultures.

Tunisia is an Arab country with a Muslim majority now, but it once had a significant Jewish population. Nazi occupation during World War II, emigration to Israel, and riots during the Six-Day-War propelled most Jews out of the country. For the 1,500 to 2000 who remain (primarily in Tunis and, 325 miles to the southeast, on the island of Djerba), there is no bigger holiday than the relatively obscure religious festival of Lag B’Omer.

Taking place on 18th day of the Jewish month of Iyar, it celebrates spring (and, like most festivals at that time of the year, includes hope for fertility as the land “returns” to life”, and plenty of hens’ eggs as symbols). Although the number of year-round Jewish residents is shrinking (perhaps 1-1,500 all told), several thousand pilgrims, primarily those whose families once lived in Tunisia, still descend on the island of Djerba each year.

Although its current building on the island (just off the coast at Gabès) is less than a century old, a synagogue has been on this site for more than 2000 years. There are many legends around El Ghriba Synagogue. One says that a “holy stone” (probably a meteorite) fell to earth exactly here (it’s housed in a niche behind the sanctuary). Another says the stone is from the altar of the First Temple of Jerusalem, which was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC.

During the festival of Lag B’Omer observant Jews gather at the El Ghriba Synagogue. Did these young women write their names on hen eggs? That’s confidential, they smile

Perhaps most surprising is its name: El Ghriba refers to a “wonder-worker”, a specific woman whose body survived a fire unscathed, and is said to grant fertility to female petitioners. During Lag B’Omer, women hoping to become pregnant write their names on hens’ eggs and place them in the niche alongside the holy stone, along with prayers to El Ghriba. Details of the ritual over the centuries are up for debate, but when I visited the synagogue, there was a long line of young women waiting to place their signed eggs in the niche.

The festival, which originated in the Sephardic community of Jews who lived in Spain and other Mediterranean lands, draws both the religiously observant and the spectator to El Ghriba. A key part of the celebration is the procession of the menorah. Unlike the rather sedate candelabra seen in most Jewish households and temples, this is an over-the-top wedding cake of a wooden candelabra mounted on a pushcart.

During the festival of Lag B’Omer there’s plenty of shopping. But be sure to put on a scarf if you enter the synagogue

Not that anyone can see it after the first block or so of its progression through town on Lag B’Omer. The tradition is to throw scarves on it. Masses and mounds of wisps of silk are collected on the menorah, and hundreds of people – men, women and children – walk behind the mound of colorful fabric as it makes its way back to the synagogue. (Since head coverings are required of women entering the synagogue, this huge accumulation of scarves is put to good use throughout the year – bare-headed female tourists are each handed one when they enter.)

The whole day is filled with celebration and feasting (the most amazing food comes out of the rather primitive kitchens in the complex across the street from the synagogue). Prominent Muslim politicians come from Tunis to speak to the crowds, and (at times) the security personnel almost outnumber the visitors. There was a terrorist attack in 2002 that killed more than a dozen German and French pilgrims who’d come to celebrate Lag B’Omer, and the Tunisian government is determined to prevent a recurrence by stationing sharpshooters on rooftops, mandating police checkpoints, and other security initiatives.

The market town of Houmt Souk, which also serves as the capital city of the island, contains a welter of shops and open-air booths filled with the specialties of the region, including pottery, jewelry and baskets. Be sure to ask one of the vendors for a demonstration of the “magic camel” – a pitcher with holes in both the top and the bottom as well as a spout. The vendors love to show tourists that if they pour water into the hole in the bottom, then flip it over, the water doesn’t come out the bottom, but is “magically” poured out through the camel’s head spout.

The lively cooperative fish auction is something you’ll not see in other markets, where the wares are typically sold by individual vendors.

Fine dining and great places to stay are available in the larger tourist-oriented towns of Tunisia. Near the capital city, you can’t go wrong with one of the eateries in the posh suburb of Sidi Bou Said (for example, Au Bon Vieux Temps). On the island of Djerba, try Fatroucha, near the town of Middoun. Along the Tunisian coastal road between Tunis and Djerba, any of the seaside restaurants around Sousse are good choices.![]()

Writer and photographer Susan McKee travels the world from her base in Indianapolis, Indiana