When American lawyer Jamie Bowman took on an overseas contract to build a strife-torn African territory’s new legal framework, she didn’t expect an explosive assignment.

But in the battered town of Juba, in South Sudan, she found herself taking shelter from an ammunition dump blast and sharing the underside of a sink – the most solid hiding place in her sweltering tent – with several lively lizards.

It was 2006, and Bowman was on contract to USAID (the U.S. Agency for International Development). But none of the challenges of her earlier postings equaled the rigors of this region shattered by decades of ethnic strife and instability.

Fortunately, Bowman is difficult to deter, even in the face of broiling temperatures, out-of-control goats, moldy showers, the skin-burrowing putzi fly, unexploded land mines and a devastating attack of malaria.

Worse, she was there at the urging of a boyfriend who had decamped for a better job in wealthy, air-conditioned Dubai.

It was only one global adventure in the life of an international development professional going forth to do good in countries where the rule of law ranged from absent to severely lacking the elements necessary for thriving economies. Her wild ride through territories most travelers fear to tread skirted emotional and physical challenges from an unwanted bribery lesson with rapacious Russian police to a narrow escape from an angry mob in Bangladesh to life in a shipping container in terrorist-plagued Kabul with an irrepressible Argentinian boyfriend.

These and other tales are recounted in Bike Riding in Kabul, a 331-page account of Bowman’s life in international foreign aid development published by Boyle & Dalton and available on Amazon.

Bowman’s wide-ranging travels began in 2000 as a US government contractor working in the uncomfortable and sometimes perilous world of overseas aid, which she found was not for the faint of heart.

The global adventures that followed were often emotionally as well as physically taxing. Bowman’s page-turning memoir is not only an account of travel at the sharp end but a highly principled woman’s journey through a rough-hewn, mostly male-dominated web of bureaucracy, inefficiency and often, indifference to the public good.

Bowman’s overseas odyssey began in deceptively low gear, supporting the work of senators in the Assembly of Micronesia in the remote Western Pacific, where “life moved very, very slowly despite friendly people, fantastic weather and world-class tuna….”

Eager to pick up the pace, she signed a long-term contract for a USAID-funded project in Kosovo, whose bloody war of independence finally ended in NATO’s defeat of Serbia. Bowman’s task: help the former Serbian province find its feet as a newly minted country.

As Bowman’s book progresses around the world it is not only a tale of off-grid adventure but a primer for those who think that wars end when fighting stops and that emerging countries become functioning democracies with a stroke of the pen.

Instead, what follows is the grunt work: painstaking, patience-testing, often mind-numbing toil to construct a foundation of intricate laws that may be stymied at every turn by bureaucracy, political opposition, corruption, criminality, incompetence and even international meddling.

Arriving in Kosovo in 2002, Bowman had her first glimpse of the underside of international development. working with USAID, an organization that touts its humanitarian goals, but often relies on people lacking compassion and a commitment to democratic decision making.

In the years of hardship postings and hard knocks that followed — on contract to USAID, the Asian Development Bank, World Bank, and a British version of USAID – she would encounter enough frustrations to send most workers fleeing for the airport.

But there were also rewards, personal as well as professional. In Kosovo, she succumbed to the dazzling blue eyes of an Argentinian engineer, in a coup de foudre that smoldered through years of hardship postings and disappointment. But Roberto’s intrepid but intermittent presence would help sustain her when the frustrations of the posts were too much to bear.

The affair began inauspiciously when he recruited her to help push a car loaded with cement – and a crying baby – out of a dangerous traffic snarl. After this unlikely first encounter, she writes, “he gave my hand a firm but tender squeeze, leaving a gritty smudge on the back of my hand.”

But even romance could not overcome the irritations of her work environment. And Bowman soon drew the line and set off on the road again. “By staying, I’m giving tacit approval to the bullying and bad management,” she said. “I don’t want to be a part of that.”

Argentinian engineer Roberto joins Bowman for ice cream in Moscow but often disappears in less developed countries.

It was a prelude to years of battling for the public good in foreign countries, taking wins where she could. A journey fueled by an adventurer’s sense of excitement at exploring new cultures and understanding their histories.

Gamely armed with an 880-page history of Ukraine, she touched down at her USAID posting in Kyiv. It was 2003 and Ukraine, just emerging from decades under Soviet control, was on the verge of an Orange Revolution driven by citizens demanding a market economy and democratic government.

Bowman was tasked with training a group of local lawyers, in spite of dampening advice from a colleague who oversaw the project. “There’s rampant corruption,” he told her, “no justice from the courts, high unemployment, poor health care, significant exploitation of young women, crumbling buildings, the list goes on and on.”

A trip to a swimming pool in one of the new luxury hotels gave her a first hand view. After bribing a staffer for an “unofficial membership” she returned to the locker room after her swim to find “two extremely tall modelesque blonds standing naked in front of the mirror,” one wearing Bowman’s clunky snow boots.

“Anywhere else, their youthful appeal would have landed them jobs that would allow them to keep their clothes on,” she lamented. Instead, poverty drove them to make their living “consorting with the fat businessmen who stayed in the hotel. It was heartbreaking.”

If Ukraine’s poverty was dispiriting, the destitution of Bangladesh, Bowman’s next stop, was far worse. Her first view of the capital, Dhaka, was that of a dystopian movie – garbage-littered streets, half-naked children standing by the roadsides, emaciated women chipping bricks into pieces under a broiling sun. And the lowest-caste workers living in shelters “that didn’t even rise to the level of shacks.”

Life for women was even more dire, with misogyny rife and any unescorted female fair game. “If I encountered a man, whether on elevator or stairs,” she was advised, “I should stand to one side, place my arms over my chest and turn towards the wall.”

Most alarming, a picturesque river excursion led to near violence by an anti-American village mob: “We were on a finger of land surrounded by water, so there was nowhere to run. I was terrified by how things might play out.” She narrowly escaped with the intervention of a local man who recalled the kindness of strangers during an agricultural course he had taken in Nebraska.

Bowman landed next in Moscow, leading a World Bank credit reform project. It was 2004, after President Boris Yeltsin’s shambolic reign had given way to tough-talking successor Vladimir Putin, who promised Russians a new era of stabilization.

What she found was an emerging country with a thriving oligarchy, exploding criminality, and rampant corruption that permeated all levels of society. In one too-close encounter she fell afoul of bribe-hungry police who checked her temporary residence permit – and found it two days overdue. Arrested, and threatened with a stretch in a pestilent Moscow jail, she bargained her way out for an agreed sum of $10 in rubles.

Those experiences did not dim her enjoyment of the city’s cultural splendors, even viewed on a backdrop of Chechen terror attacks following Putin’s brutal war against the separatist territory. It was a time when mafia warfare was played out on the streets. Lawlessness spilled into carnage on the roadways, where homicidal driving was the norm.

But the perils of life in Moscow paled beside those of Kabul, her next assignment, where she joined Roberto, who worked on a contract to rebuild schools and clinics. But the dream faded at first sight of Roberto’s living quarters — a shipping container in a gated compound.

“He opened the container door, and I was hit full in the face by a blast of stale air …I silently surveyed the tiny room. There was a makeshift desk, one chair, a steel clothes cabinet and a bed too small for two people. It was horrible.”

The pair survived a near miss from an off-kilter rocket attack aimed at the U.S. embassy nearby. But it was Roberto’s enthusiasm for an early morning bike ride along the Kabul River that pushed Bowman to her limits, when she found herself riding alone, after he abruptly vanished. Fearing kidnapping, she began desperately searching for him, lost control of her bike and sprawled on the pavement painfully after hitting a rock.

When Roberto turned up, smiling, from a side street, “there was no point in talking. I simply pointed my bike toward the disgusting garbage-strewn Kabul River and let it roll down the steep bank. I stomped back to the compound by myself, leaving Roberto to retrieve the bike from the filthy water and muck.”

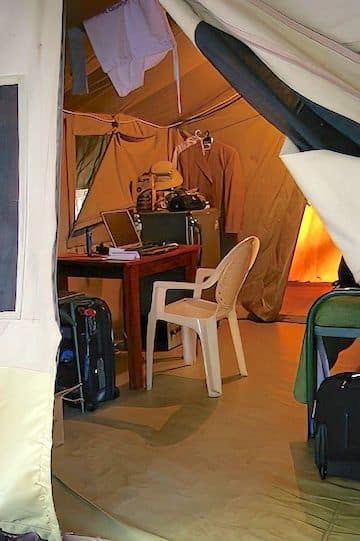

Bowman”s apartment in Southern Sudan was essentially a tent that was less depressing than the government building where she worked.

The relationship survived the bruising incident. And it was at Roberto’s insistence that Bowman took her next job in South Sudan, where he was to work on a road-building project. But by the time she arrived in Juba, the project was delayed and Roberto had taken another in Dubai, living in an air-conditioned high rise near the centre of town.

In Juba, she broiled in 90F heat in a tent encampment, working in a crumbling ministry building where “the windows were missing their panes and secured by chicken wire and plastic sheeting.”

The area was home to herds of feral goats: “on the road, sleeping under cars, on the top tree branches, and even perched on the tombstones in the cemetery.”

Malaria was endemic, and before long Bowman fell prey to the disease, which kills some 600,000 Africans each year. She survived with the ministrations of the “Hollywood handsome” camp doctor. “After almost a week in bed, I looked and smelled awful, but I was too weak to care.”

After 18 exhausting months, Bowman moved to the Rwandan capital Kigali to help USAID establish a much needed credit bureau. It was 14 years after the 1994 ethnic genocide in which some 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were massacred. Although many Rwandans preferred not to speak of it, her job of building modern financial institutions occurred while “bodies discovered around the country were still being brought to the Genocide Memorial for a dignified burial.”

She had reunited with Roberto, now working on a Rwandan school construction project. They celebrated his birthday with a visit to the Virunga National park, a four-hour drive from Kigali, and a haven for adventure tourists. After a two-hour hike, they had a front row view of a colony of gorillas, once nurtured by Dian Fossey, that included females, their lively offspring, and a watchful male “who occasionally emitted short grunting noises, less than gentle reminders that he could easily tear our heads off.” But she added, “It was magical.”

Less magical was her romantic life. And after a chilly parting from Roberto, Bowman set off on a round-the-world trip, visiting friends and family and sightseeing from Sydney to San Jose. But her carefree spirit came down to earth abruptly with a new posting to Afghanistan. It was early 2010, five years after her first term in Kabul: “I swore I’d never go back. The lack of collaboration, the incredible waste of funds, and the excruciatingly slow progress were so disheartening.”

But faith in the new Obama administration, and hope for the “surge” of troops and aid projects, spurred her on. It was a massive, and ultimately failed attempt to stabilize Afghanistan militarily and economically before a planned drawdown of American forces.

Bowman arrived to a scene of chaos. USAID staff on the ground were “making no secret of how much stress the new arrivals were causing them. We had to be fed, housed and transported, and most importantly, deployed – anywhere…to make room for the next batch of advisors arriving shortly.”

After three months in the remote Panjshir mountains, she arrived back in Kabul to oversee a $108 million project to support emerging Afghan enterprises. But it followed an excoriating investigation by the Washington Post, which exposed “massive fraud” in Afghanistan’s biggest lender, Kabul Bank. Bowman tried in vain to alert the Central Bank contractors to these grave allegations that they had overlooked. But they dismissed her concerns as rumors, and promptly filed an official complaint against her. Another followed when she questioned the bank’s interest rate policy.

It was the last straw for a dedicated professional who believed in people above politics and above all, accountability. After her warnings were ignored, she sent a detailed memo stating the “real problems at the Afghan Central Bank and its oversight of the industry,” to the Office of Economic Growth under which she worked.

Her concerns were vindicated by the near collapse of Kabul Bank, amid a scandal that exposed close to $1 billion in losses. Depositors fearing the loss of their savings were furious. Fingers were pointed at the Central Bank and its contractors, who failed to notice Kabul Bank’s fraudulent concealment of millions of dollars in unsecured loans given to political cronies.

When exposure did not lead to accountability, she headed for the exit. “I’m leaving because no one is being held responsible for the failure of Kabul Bank,” she told a colleague. And the Central Bank contractors who ignored the Kabul Bank’s fraud still held their jobs. (Kabul Bank’s two top officials were later charged and jailed, but most of the money was never recovered.)

To walk off her “soul-crushing” disgust, Bowman reunited with Roberto in Spain and joined pilgrims making a 100-kilometer trek along Spain’s El Camino de Santiago trail.

At her destination, her prayers were answered. A Wall Street Journal article headlined a USAID report denouncing the inadequacy of the Central Bank contractors and the lack of capacity to detect fraud in Kabul Bank. The U.S. Government ended the contract supporting technical advice for the Central Bank, which terminated the jobs of the contractors who had criticized her.

It was a fitting finish to a decade-long adventure that begs a mini series to follow. But as Bowman ends her last chapter there is a hint of more to come.

It was a fitting finish to a decade-long adventure that begs a mini series to follow. But as Bowman ends her last chapter there is a hint of more to come.

Roberto, who has just won a job in Cambodia, asks, “any interest in going to Phnom Penh…I mean with me?” Stay tuned for volume two.![]()

Olivia Ward was a foreign affairs reporter, correspondent and bureau chief for the Toronto Star at the UN, in the former Soviet Union, Europe and Middle East, and columnist for the New Internationalist. She is now a documentary filmmaker.