Lebanon was falling apart. Then came the 2020 port explosion

Lebanon was falling apart. Then came the 2020 port explosion

By Susan McKee

Lebanon is a theoretical country, cobbled together from shards of the Ottoman Empire following World War I. Europe’s Great Powers hoped the different religious communities within its borders would work together to create a cosmopolitan nation. Unfortunately, Lebanon’s Christian and Arab oligarchs and their family clans more often have colluded than cooperated. Khalil Gibran, a Lebanese-American poet born to a Maronite Christian family, worried about his native land’s survival. “What will remain of your Lebanon after a century?” he wrote in the 1920s.

Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse by Charif Majdalani chronicles less than two months in the life of Lebanon’s capital city. It reads like an extended lamentation that documents the unending challenges of living in a failed state that is brought into sharp relief by a massive explosion on August 4, 2020 that destroyed the city’s port as well as many of the capital’s historic neighborhoods.

Once home to the Phoenicians, a maritime culture that flourished for almost 3,000 years, Lebanon was under a French mandate from 1920 to 1945, and one would assume that during that time the niceties of Western democracy were put in place. You know: the rule of law, checks and balances in governing, and so on.

As Majdalani writes, “In the Lebanese worldview, France was never seen as an occupying power, but rather as an ally” who drew the country’s borders to include as many Christians as possible. Christians in Lebanon had long felt “closely connected to France,” and “had adopted the French language and culture well before the period of the Mandate.”

Crucially, the dominant positions in the government were allocated along religious lines, with those going to Christians having the most power.

The first thirty years of independence, from 1945 to 1975, saw a blossoming of business and culture. Beirut, resplendent with “cabarets and nightclubs,” often was referred to as the “Paris of the East.”

In Majdalani’s view, however, “the new Lebanon was not a Western country, nor did it belong to the Arab world. This was the famous affirmation of national identity by a double negative.”

According to the author, the civil war which dragged on from 1975 to 1990 brought the end to this idyll of “unbelievable opulence” and “cultural and economic vitality.” These 15 years weren’t just a civil war between factions of the Lebanese people, but also “a foreign war, because the Palestinians, Syrians, and Israelis also were involved.” The war concluded with the entire country falling to Syrian control.

Majdalani says during this period “a system of governance that was entirely based on clientelistic mafia practices” was developed between the new generation of warlords and the Syrian-occupying forces. This arrangement culminated in the current malaise: “poor governance, corruption, and clientelization of the citizenry based on community affiliation” combined with “the absence of any regulatory authority or control over the country’s social or economic life.” In other words, Lebanon’s “political leaders [are like] mafia bosses”.

Hence, Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse is Majdalani’s attempt to capture what went through his mind, day by day, last July and August.

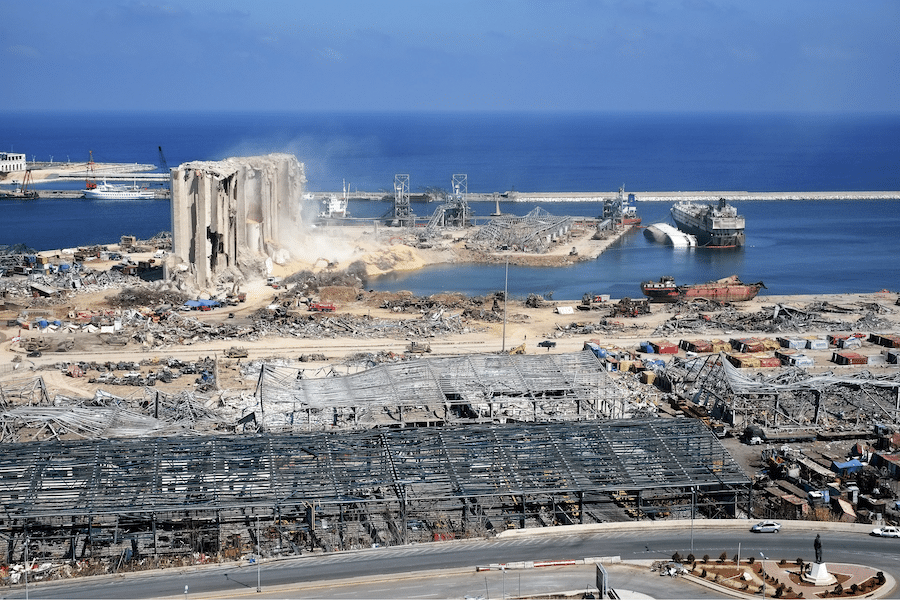

Beirut’s port following the August 4, 2020 explosion of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate Photo by Rashid Khreiss, Unsplash

In the United States and Europe, much of the discussion the past two years is about COVID-19 infection rates and mask mandates. Majdalani mentions the epidemic only in passing he and his friends continue to dine out, his wife, Nayla, goes to her office, and their kids, Saria and Nadim, are in school each day.

How all this living is paid for is unstated. Presumably, Majdalani has royalties from his books, and he is still teaching French literature at the Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut (at one point he notes that his salary hasn’t changed but “it’s worth six times less than it was six months ago”). His wife seems to have an income as a psychotherapist, but currency — cash money — is hard to come by. In his July 1 diary entry, he recounts spending the day “running from one bank to the other” and ending up “completely muddled and giving up on the whole thing.” He says he pays his bills with a combination of checks and cash.

By July 7, he’s in a funk. “The only real evidence I have that something is actually going on is the direct impact it has on my daily life,” he writes. “And that impact is palpable in my worry and anxiety, my mind being permanently occupied by catastrophic scenarios…. How do we face our future and our children’s futures in this ruin of a country…. It feels like a bereavement, a muffled, almost muted bereavement, repetitive, exhausting.”

Majdalani was born in Beirut in 1960 but spent much of his childhood in the countryside. He’s trying to purchase some rural land so that his children can have the same halcyon existence. Except that as lifelong city-dwellers they’re frightened by the wildlife in the fields outside the city.

In his visits with a rural landowner during the months covered in his diary, Majdalani notes that the accepted medium of exchange for large sums – such as his proposed land purchase – is cashier’s checks, presumably issued by one’s bank against the amount on deposit. But cash withdrawals are impossible and the landowner demands cash to complete the sale.

The electricity grid has collapsed, so that proprietary generators are the only power source. At night the streets are mostly dark, conveying an “impression of profound gloom”. Yet, the author’s apartment building remains well-lit.

Public works projects from forest service aircraft maintenance to dams are incomplete or shoddily constructed as the money allocated to pay for them simply disappears. Instead of recycling or incineration as required by contract, trash is compacted and dumped into the Mediterranean Sea.

Lebanon’s mountains have drawn migrants and tourists for eons. The region was seen as a natural paradise with its abundance of water and greenery, Majdalani recounts. During the years after the civil war, “Numerous dams were built, destroying the mountains, the natural sites and landscapes, laying waste to valleys, gorges, and arable land.” He laments more than once that the countryside is littered with failed projects, such as the now-leaking dams. “Nothing is known about the billions of dollars that were spent on them, involving fake invoices, cooked books and gigantic amounts of siphoned-off funds.”

Misuse of public money is a frequent refrain. Majdalani points to the administration service for the railroads, which continues to operate at great cost “although there has not been a single rail or a single train anywhere for sixty years.”

The Lebanese pound is officially tied to the American dollar so that transactions can be made in either currency, but that conceit has unraveled leading to wild swings in the black-market exchange rate. He recounts his attempt, at the beginning of fall 2019, to withdraw $6,000 from his bank one day, and the teller’s stammering deflection as he refuses the request “because that was a lot of money.”

Majdalani ties the banking crisis to lack of regulatory oversight as well as corruption, reporting that Lebanese banks had established “dizzying Ponzi schemes” offering excessive rates of interest that are made possible by deposits of subsequent customers, “without any investment policies whatsoever.” At the first whiff of trouble, large depositors whisked their billions offshore, while ”thousands of people were standing around the hostile tellers begging for one or two hundred dollars of their own money.”

As July 2020 continues, his diary entries become more depressing. Periodic protests fill the streets. The coronavirus spreads and a lockdown looms. Restaurants get creative in their workarounds when commodities as disparate as meat and avocados become scarce. On July 24 he writes, “There have been Israeli planes roaming skies for days now…. But nothing happens.” Yet another of his close friends makes plans to move abroad.

Tuesday, August 4, 2020 at 6:07 p.m. Everything changes with the port explosion. “I’m petrified as I feel the terrace come and go beneath me like an old swing, and I think it’s obviously an earthquake,” he writes.

Of course, it wasn’t a natural disaster. “The devastation from the explosion reached almost every part of the capital to varying degrees.” Tens of thousands of houses, apartments and skyscrapers blown apart. Four hospitals and the Sursock Art Museum obliterated. “In five seconds: two hundred dead, one hundred and fifty missing, six thousand injured, nine thousand buildings damaged, two hundred thousand homes destroyed” as well as retail stores, restaurants art galleries, and more. His paean to the destruction is as terrifying as it is lyrical.

The cause of the explosion is officially undetermined, but Majdalani knows where to apportion blame. As has been extensively reported, a stockpile of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate, a highly explosive chemical often used as fertilizer had been offloaded under mysterious circumstances in November 2013 and stored at the port. “Six years of lack of transparency and accountability, the result of thirty years of corruption and lies, of mafia-like practices, of collusion between the various arms of government, the various ministries, political parties, and their clients, of devious geopolitical scheming and sinister warmongering by bloodthirsty, criminal militias, all this was concentrated, condensed in the most terrifying manner, and generated that five-second apocalypse.”

Majdalani’s diary ends August 19, 2020 with no resolution ether to his personal situation or that of Lebanon itself. The government resigned in the wake of the explosion, but no one knew what will come next. “Our lives…thrown to the wind,” he concludes.

Susan McKee is a travel writer in Indianapolis, IN. Her previous stories for the East-West News Service profiled Nairobi, Tunisia and Armenia.