The Eyes of Trunyan are upon you so don’t forget to contribute before leaving. Photo by David DeVoss

By David DeVoss

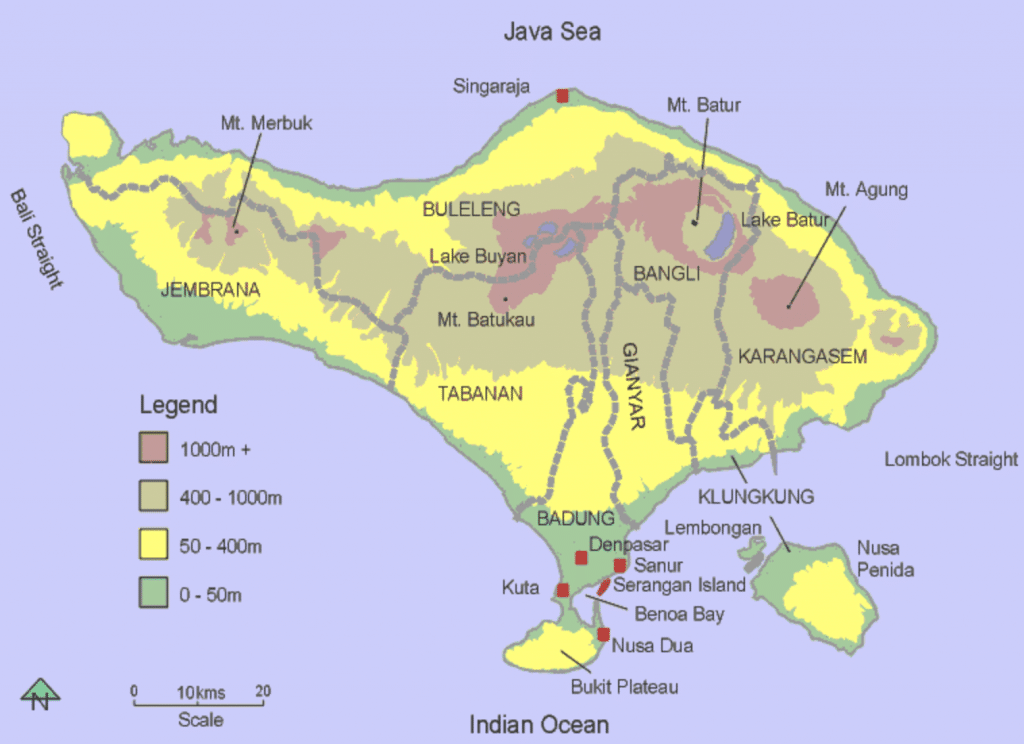

Deep in the mountainous heart of Bali, away from the island’s pristine beaches and resort hotels, two enormous volcanoes slumber fitfully. The larger, 9,800-ft. Mt. Agung, erupted violently in 2017, closing the airport and forcing 100,000 Balinese to evacuate their homes. Toward the center of Bali is the smaller but more spectacular Mt. Batur. It has a fiery summit that erupts less often but bubbles throughout the year spewing bursts of magma into the night sky.

Bali is moored in the center of Indonesia, an Islamic archipelago consisting of more than 17,000 islands that extends 8,546 miles east to west along the Equator. About 84% of Bali’s 4.3 million people are Hindu. Their religion, and the colorful way it is celebrated, annually attracted more than 6.2 million tourists before the island closed for Covid in 2020.

Balinese temples celebrate Hindu epics every day.

Bali reopened several weeks ago to citizens of 19 countries. The recent arrivals, like those in years past, come to attend Hindu celebrations in shrines perfumed by incense and festooned with floral garlands. They sit in rapt awe, enveloped by sounds from gamelan orchestras while sensuous temple dancers interpret scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

Indonesia has 126 volcanoes, two of which – Mt. Agung and Mt. Batur – are on the island of Bali.

North of the inland market town of Ubud, however, tourist resorts and handicraft markets give way to small villages like Trunyan, pop. 300, that belong to a mountain people called the Bali Aga.

I first heard about Trunyan in the 1970s when I was a Time Magazine correspondent in Saigon. According to local lore, the village was “discovered” by war photographer Sean Flynn, whose swashbuckling reputation equaled that of his Hollywood father, Errol. Flynn heard rumors of a mysterious people, unwelcoming of outsiders, residing in the shadow of an active volcano on the far side of Lake Batur, a water-filled caldera created by a volcanic eruption 25,000 years ago. What he found after crossing the lake was a settlement of primitive Bali Aga who called themselves “the original Balinese.”

There’s plenty of time in Trunyan to hang out and say goodbye to the dearly departed. Photo by David DeVoss

Understanding the Bali Aga

Unlike Balinese Hindus elsewhere, the Bali Aga do not memorialize the dead with elaborate cremations. Instead, they place their deceased kinsmen beneath a large tree and let nature reclaim the bodies. In my imagination, Trunyan seemed both dreadful and exotic at the same time.

On my first R&R outside Vietnam, I went to Bali, rented a motorcycle and headed to the Balinese highland town of Kintamani. That night from a losman veranda I stared across the vast lake and watched Mt. Batur spit fire into the night sky, imagining what it must be like to live under the volcano.

Events in Vietnam cut short my vacation and it wasn’t until more than 30 years later that I returned to Bali’s highlands determined to finally meet the Bali Aga.

I left Denpasar in the morning and headed north past Ubud and into a succession of terraced paddy fields that gradually rise toward Mt. Batur. After driving to a beautiful temple town called Penelokan, I walked down a twisting path to Lake Batur and found a man with a hollowed-out prahu willing to take me across the lake to Trunyan for $2.

Searching for Trunyan

It took the better part of an hour for us to paddle across the lake. Upon reaching the distant shore, Trunyan was barely visible through the vines shrouding the ancient village. I walked up a muddy trail through a bird-filled jungle and arrived at a traditional Balinese village whose portal was graced by a plate full of human skulls.

Despite their ominous welcome mat, the people of Trunyan were more indifferent than hostile to a stranger in their midst. Neither did they object when I asked to visit their ancestors. A group of young men standing just outside the village wall with nothing to do escorted me to a row of open graves beneath a massive Banyan tree. And then they walked away with nary a glance at the camera I extracted from my bag.

I was breathing a sigh of relief when one of the teenagers turned back toward me and said with utmost seriousness, “Before you go don’t forget to leave a cash offering beside the skulls.”

Left beneath the tree with my boatman, who quickly excused himself and headed back down the hill, I began walking toward the graves through a landscape littered with bleached femurs, tibias and well-gnawed vertebrae. More disconcerting than the piles of bones were the yapping of village dogs that clearly forestalled any semblance of eternal peace.

An Ossuary of skulls

The graves themselves were surrounded by tented cane enclosures of the sort that might support vegetable vines in conventional villages further from the volcano. Inside each reed crib lay a skeleton slowly sinking into the jungle floor.

As a young journalist, I found myself on battlefields in Vietnam, Cambodia and El Salvador. But there was no smell of death coming from these corpses. “It’s the tree,” a young boy explained. “It’s magic.”

Because they do not disintegrate rapidly, the skulls of Trunyan’s dead are arrayed in ever-watchful galleries.

Dead Watch Over the Living

Trunyan is not unique in Indonesia. Northeast of Bali on the pinwheel-shaped island of Sulawesi (also called the Celebes) the Toraja people place their deceased in caves or niches overlooking their villages. Once decomposition is complete, wooden effigies carved to resemble the dead are seated side by side on limestone balconies so they can continue watching over their progeny working the paddy fields.

For people raised in the Christian and Islamic faiths turning cadavers into compost seems a bit primitive. But that’s exactly what an American company called Recompose is doing in Washington State.

Located in Kent, Washington just south of Seattle, Recompose uses “natural organic reduction” to turn a human body into one cubic yard (765 liters) of soil weighing 1,500 pounds. The process takes 30 days.

Turning Grandma into a vegetable garden may not appeal to you. But in progressive Seattle NOR is embraced by environmentalists who point out that cremating Granny releases one metric ton of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Funerals are so 20th century. Indeed, non-religious “celebrations of life” now have become “carbon cycle ceremonies” most often conducted on a meadow or mountain where the compost will be spread.

Now that America finally has caught up with Indonesia environmentally, it may be time for directors of carbon cycle ceremonies to familiarize themselves with the story of Rama and Sita, or at least learn to play the gamelan. ![]()

East-West News Service editor David DeVoss is the author of the Insider’s Guide to Indonesia.