Fairies are said to calm the horses living at the Irish Stud, so ethereal sprites are welcome though seldom seen using their fairie doors.

By Liz Campbell

Why do we travel? To stand awestruck at nature’s vibrant sculpting of rock and sand in the Grand Canyon or Rainbow Mountain? Or delight in human landscapes like Rome or Paris where every corner offers another architectural gem?

Perhaps we seek enlightenment – why did early humans construct the standing stones of Stonehenge, or the hypogeum of Ħal Saflieni in Malta? Or we want to discover other cultures by exploring the golden stupas of Myanmar or standing before Uluru with the same wonder as did the first inhabitants of Australia.

The world is filled with such treasures. But in a very few places, our explorations move us beyond the mortal realm, to a land where the line between the mystical and the mortal is delightfully blurred. One such is Ireland.

It only takes a few days on this island before my pragmatic soul has its first encounter with that other world. On the River Boyne in County Meath, we’re just a few hundred meters from the site of one of Ireland’s most famous battles.

The deposed James II, a descendent of Mary Queen of Scots and Charles I was the last Catholic King of England. Backed by Louis XIV of France, his forces in 1690 battled the Dutch Protestant, William of Orange who, with his wife Mary, had been invited to take the throne of England. To complicate matters further, this Mary was actually the daughter of James II.

William’s victory in Ireland not only put a Protestant king firmly on the throne of England, but it also put this country under English control. It would be two and a half centuries before the Republic of Ireland would sever those ties completely.

Ross Kenny is the owner of Boyne Boat Tours, and as we make our way down the peaceful River Boyne, he describes that bloody battle as Ireland’s Game of Thrones.

It’s an apt description because we’re in a currach – a unique Irish craft that looks like a canoe on steroids. Kenny builds these and they featured in the popular television series. Indeed, he himself was in several episodes. “Look for the guy with the beard,” he tells us with a chuckle.

Ross Kenny owner of Boyne Boat Tours beside an Irish canoe called a “currach.”

Land of the Giants

Being an Irishman, with Blarney in his blood, it isn’t long before we move from the historic battle to other, other-worldly ones – those of the legendary giant, Fionn Mac Cumhaill (pronounced Finn MacCool). He tells how the handsome Finn heroically slew the fire-breather Áillen, who wrought annual destruction on the mythical Irish capital of Tara.

It was here in the River Boyne, that Finn caught the elusive Salmon of Knowledge. According to legend, nothing would remain unknown to the one who succeeded in catching this fish. Thus Finn added wisdom to his other merits.

But tales of Finn are literally cut short. A tiny door at the base of a tree on shore catches my eye. Smaller than a sheet of paper, its bright blue color makes it stand out from the underbrush. “What’s that?” I ask.

“Oh, that’s a fairy door,” is Kenny’s offhand explanation. “It’s an opening to the other world.” An open door is a sign of welcome, he adds with a twinkle. Alas, while we pass four of these – each a different color – they are all firmly shut.

We’re amused, but in Ireland, fairies are taken very seriously. No one in this country would consider damaging a fairy ‘mound’ or a fairy ‘fort’ – and these are everywhere. One can even purchase guides to locate them. Indeed, destroying them can have dire consequences, according to an article in The Irish Times: Business tycoons in Ireland have been left penniless and the planning of motorways have been interrupted, and every time fingers have been pointed towards the fairies.

Not unreasonably, I begin to watch for these tiny entranceways. And astonishingly, fairy doors pop up in the most extraordinary places.

While cruising the River Boyne you can see a blue fairy door if you look quickly.

Horse Heaven

At the Irish National Stud in nearby County Kildare, five great Irish racing champions, now retired, are peacefully munching grass. They don’t look particularly spectacular as horseflesh goes, but these thoroughbreds are royalty, and their progeny worth many thousands.

Japanese Garden in the National Stud of Ireland

Ireland has produced some of the finest racehorses in the world, and the National Stud belongs to its people, annually raising millions for the national coffers.

The Stud’s original founder was the eccentric Colonel William Hall Walker, scion of a Scottish brewing dynasty. Intrigued by the idea of creating peace and harmony through the natural world, he devised the idea of building the now famed Japanese Gardens here. In 1906, he brought Japanese Master Horticulturist Tassa Eida and his son Minoru to design and lay them out.

Trees, plants, flowers, rocks and water, are used to symbolize the ‘Life of Man’, tracing the journey of a soul from oblivion to eternity. The project would take four years to complete and today the serene grounds offer a seamless mix of Eastern and Western aesthetic.

In 1999, another garden, this one distinctly Irish, was added on stud lands. St. Fiachra’s Garden (named for the patron saint of gardeners) is the creation of award-winning landscape architect, Martin Hallinan.

A wholly different experience, it reflects Ireland’s monastic movement in the 6th and 7th centuries. Cells of fissured limestone are surrounded by water, while in an inner subterranean garden Waterford Crystal-shaped rocks, ferns and orchids can be found. These two gardens draw thousands of visitors each year.

In St. Fiachre’s garden, beside a woodland streamlined with weeping beech and ancient oaks, I spy a familiar sight. Peeking from the base of a tree is a miniature bright red door.

One of the gardeners working nearby sees my delight and in true Irish fashion, adds a story. He earnestly explains that fairies are important in horse breeding; they calm and soothe the horses when humans aren’t around. But when asked if he’s ever seen a fairy, he replies with an enigmatic smile and a touch of finger to the side of the nose, “It doesn’t matter whether you see them. They are here.” Clearly, fairies are an elusive race.

St. Fiachra’s Garden recalls Ireland’s archaeological and monastic history

The storyteller

It might seem strange that the Irish are so ready with a yarn, but the most important figure in ancient Irish history was the storyteller or seanachie. These bards and poets recited the great Irish and Celtic myths, tales where the supernatural was a natural part of the landscape. They have many modern-day successors and finding them takes travel in Ireland to another level.

Just north of Meath in the Cooley Peninsula, we pedal the short, six km bike path from Omeath to Carlingford with E-Bike Escapes. Our route winds alongside Carlingford Lough (the Irish term for loch), offering spectacular views of County Down across the water. And to my delight, it seems our cheerful guide, Diarmaid Rankin, has unreservedly adopted the seanachie mantle.

Waving his arms extravagantly, he launches into story mode. This landscape was home to Finn MacCool, he says, “It was Finn who built the Giant’s Causeway, [a series of interlocking basalt columns in County Antrim in Northern Ireland], so he could walk to Scotland without getting his feet wet.” One has to smile at a giant who is squeamish about wet socks.

The wondrous tale continues with Finn’s battle with his rival, the fearsome Scottish giant, Benandonner, with flaming red hair and burly beard, who comes to life with our storyteller’s extravagant hand gestures.

Though it’s not clear who won, the pair apparently lifted massive pieces of land and threw them at one another across the Irish Sea. Neither actually crossed the water – wet socks still being a problem.

The holes left by Benandonner’s projectiles filled with water to become the Scottish lochs (lakes). But one of Finn’s less-well aimed shots landed in the Irish Sea, he says, adding with a twinkle, “Today we call it the Isle of Man.”

You’ve heard of giant upheavals of land? The Irish clearly take this literally.

As we near the town of Carlingford, the rocky ruins of its eponymous 12th century castle, also called King John’s Castle, dominates the shore. Inside these massive stone walls, according to local myth, King John sat down to draft Magna Carta. Finally issued in 1215, the Magna Carta established for the first time the principle that everybody – including the king – was subject to the law.

Carlingford Castle in the medieval city of Carlingford is also called King John’s Castle because it is here he is thought to have started writing the Magna Carta

Later, over a lunch of delicious fresh fish from the self-same lough, our magical world shrinks once more. We’re at PJ O’Hare’s, a delightful pub in Carlingford. PJ, the pub’s owner, assures us that not only do leprechauns, a race of elves, exist, but he has the proof – the remains of one found in 1989. He offers as evidence its skeleton and clothing, found near a well on nearby Slieve Foye Mountain.

On the Leprechaun Trail

Diarmaid cheerfully adds that another local character, Kevin Woods, has allegedly met with the little folk, and definitively determined that there are, at this time, precisely 236 remaining leprechauns on Slieve Foye.

Of course, we set off up its slopes, all of us on the lookout for signs of leprechaun habitation. After all, if we can catch one, perhaps we can barter his release in exchange for his treasure, or so the legend goes.

It’s a beautiful walk, and we find plenty to delight our hearts: sheep peacefully grazing the hillside; striking views of the Medieval city of Carlingford; the stone remains of a deserted village; and a raggedy bush, covered with tiny pieces of colorful material.

A raggedy bush is usually a small hawthorn tree, onto whose branches people tie tiny scraps of cloth. Each scrap represents wishes either for good fortune, or for healing in which case they might tie a tiny piece of the ill person’s clothing.

A raggedy bush on the slopes of Slieve Foye is covered with tiny scraps of cloth and ribbon

There are dozens attached to this one, and it’s tempting to add our own, in order to wish for the good fortune of meeting a leprechaun. We don’t, and perhaps as a result, our delightful ramble across the hills is unproductive of little people. Our consolation might be that leprechauns are said to be mischievous and love to play tricks.

A local farmer we encounter suggests we return to Carlingford for the annual Leprechaun Hunt on these hills; but those leprechauns are ceramic, with prizes attached to them. ”The hunt is held well away from the leprechaun’s home area,” he assures us. “We’d never disturb the little people or risk them harm.”

Are you rolling your eyes? You might be interested to learn that, according to Diarmaid, under the European Habitats Directive (Ireland is a member of the European Union), the fauna, the flora and the leprechauns and fairies of this island are specifically officially protected!

How can one resist a country where the other world is so patently valued?

There are so many reasons to come to Ireland. Come for the craic – pronounced crack, this is Irish for fun and this is an island whose people know how to enjoy themselves. Come for the food – fresh, local dishes from the clean earth, the surrounding sea, and the grazing animals. Come for the Wild Atlantic Way – 1,600 miles of spectacular, rugged landscape running from Donegal to West Cork.

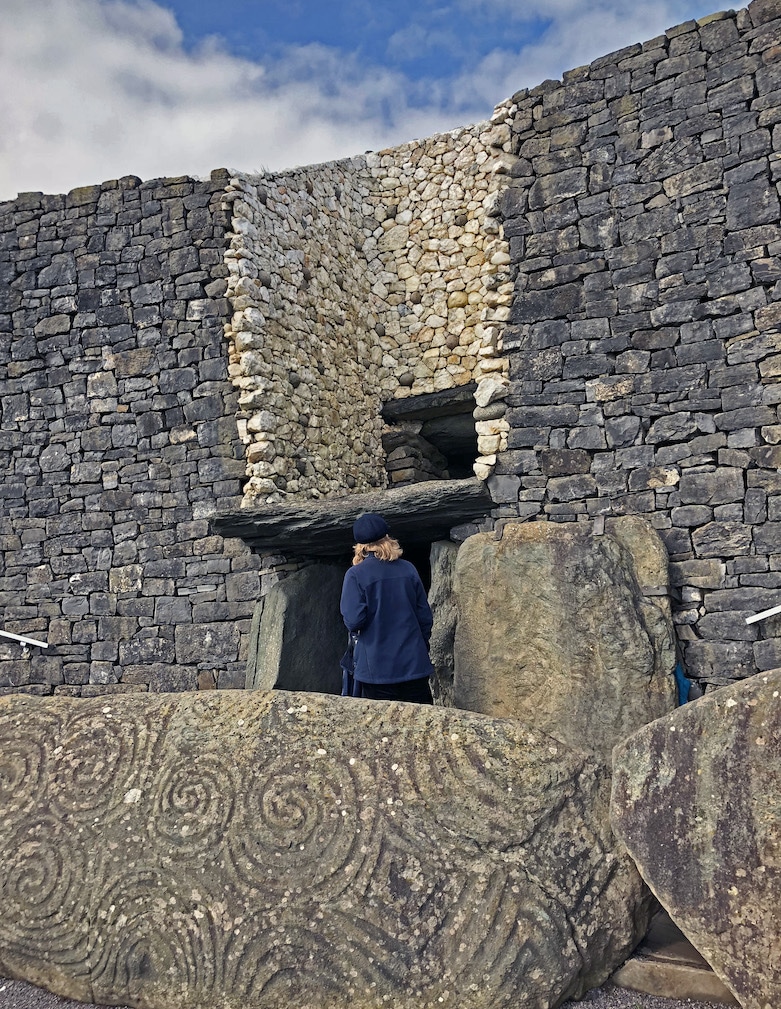

You can even come for the history – did you know that Newgrange, a magnificent Neolithic structure not far from Dublin, actually predates the Pyramids? Indeed, Ireland’s landscape is dotted with Neolithic tombs and dolmens.

The entrance to Newgrange a Stone Age tomb in the Boyne Valley that predates the Pyramids

But perhaps the most important reason to come is a chance to meet the Irish. They are inveterate storytellers and love to share the legends most of them have heard since childhood. Through these, we have a rare opportunity to step, for just a moment, outside the mortal realm.

World renowned Pre-Raphaelite artist, William Holman Hunt once said: The earliest truth that we’re taught is that there’s a world alongside this world, with spirits, not mortals, an enchanted universe of fairies, wizards, leprechauns and trolls. They are all around us. One has only to open his eyes.

The Irish manage to hold on to this truth, which might be why this country is so enchanting. It would seem that the old expression, ‘away with the fairies’ to refer to those who are distracted or even a little mad, might apply to much of the population of this island.

Come to Ireland with open eyes. Seek out leprechauns and fairy doors. If you’re lucky enough to spot an open door, its tiny resident might emerge and invite you in for a Guinness. If not, one of the mortal residents certainly will – and entertain you with a story while you drink it.![]()

Liz Campbell has been a freelance travel and food writer for more than 20 years with stories published in The Globe & Mail, Zoomer, Foodservice & Hospitality magazine and more.