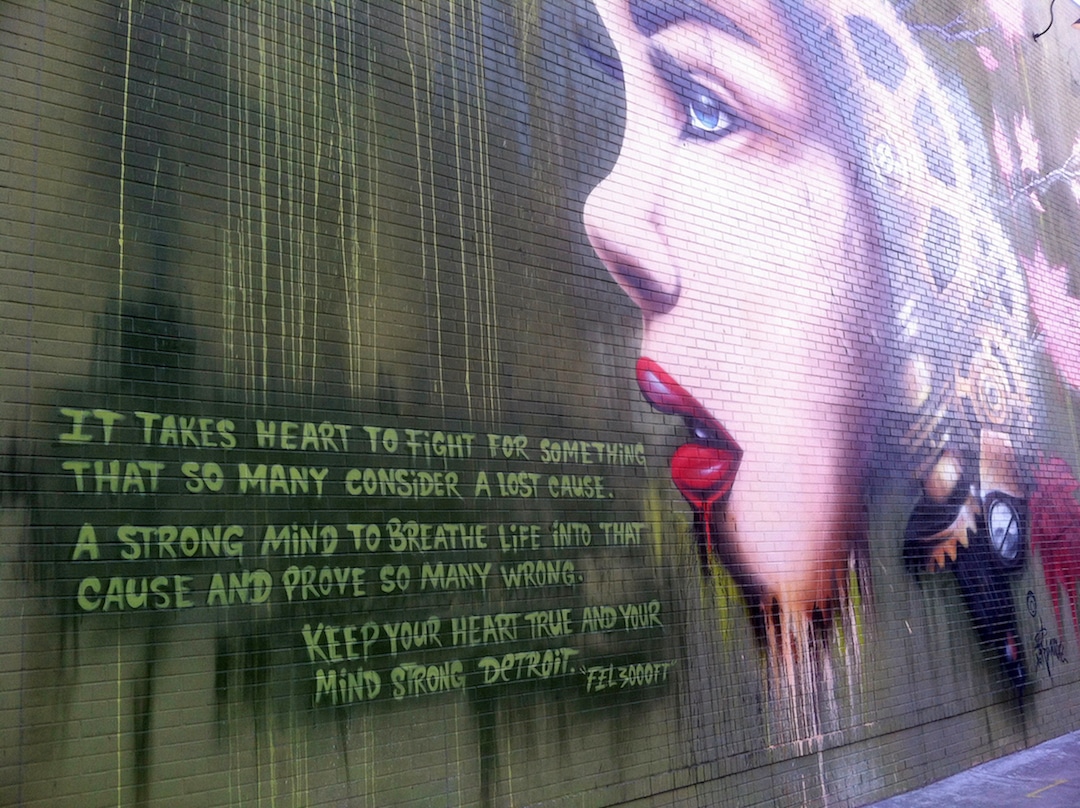

Many of Detroit’s public murais, like this one close to the QLine that runs along Woodward Avenue, are exhortations to strive for improvement and be productive citizens. Photo by David DeVoss

By Mary Bergin

Many of us root for the underdog because we’ve been there, felt that. Being pegged as a loser can turn you into a victim and break your spirit. But public denigration also can strengthen your resolve and motivate change. Working through adversity is how champions are made.

Tommey Walker and his hometown, Detroit, have chosen renaissance over retreat. As the entrepreneur told Hour Detroit magazine: “It’s like, at what point do you pivot from thinking about the problem to solving it?”

Ten years ago, Walker began his transition from graphic artist to fashion designer by printing T-shirts with the name of his newly founded company, Detroit Vs Everybody (DVE). The brand turned into a force whose fans include A-list rappers and other celebrities.

Count luxury label Gucci among Walker’s newest business partners, and “Vs Everybody” has grown into a clothing line with myriad rallying cries and inspirational messages. Two examples: “Everybody vs Injustice” and “Don’t Complain. Contribute.”

Enough Detroit Bashing

All stems from Walker’s exasperation with relentless media bashing of Detroit for being too poor, too divided, too dangerous and too far beyond hope to save. When Detroit declared bankruptcy in 2013, the city had at least $18 billion in debt, a record among municipalities nationally.

That was then, and this is now. Inflation and recovery from the pandemic continue to challenge all, but Detroit had under $2 billion in bonded debt in 2020, says Citizens Research Council of Michigan. For perspective: That is lower, per capita, than Chicago or Philadelphia.

Just as DVE spreads new and meaty messages, so does Detroit, which embraces the nickname “Comeback City.” The city’s deep dive into downtown revitalization is designed to enhance economic growth and create new tourist amenities.

The headquarters for Detroit’s fire department turned into the boutique Detroit Foundation Hotel in 2017. At ground level is the Apparatus Room restaurant. Photo by Joe Vaughn

While serving as CEO of Detroit Medical Center, Mike Duggan was always envious of Chicago’s welcoming riverfront. So, following his election as mayor in 2013, he authorized more than $200 million be spent to upgrade 3.5 miles of Detroit River frontage. The money was used to convert industrial wasteland into an attractive and secure riverwalk with gardens, playgrounds, green spaces, lounging/dining, a carousel, amphitheater and the urban Milliken State Park.

The investment provided new venues for outdoor movies, Tai chi and volleyball, exercise classes for elders, fishing lessons for children and a dog walking program.

Work on an additional two miles of waterfront began in May 2022, adding a “sports house,” garden playground, water garden and area for large-group events. “Detroit is a better place to live because of what’s been done on this riverfront,” the mayor declared at the groundbreaking.

Safe Space on the River Front

In proclaiming the program’s success he acknowledged that “Detroit has been a city divided” racially, geographically, economically and by language differences among neighborhoods. “What great cities have is a central place where the entire city can come together,” Duggan added. “For most of my lifetime, Detroit never had that.” Until now.

Marc Pasco of the nonprofit Detroit RiverFront Conservancy echoed the realities. “The city wasn’t what we wanted it to be,” he explained. “The riverfront was an absolute disaster – piles of concrete and debris.” River water was a resource for farms, then industry, but not tourism. Until now.

“Detroit has momentum now,” Pasco says. “I think everybody loves a comeback story, to root for the underdog.”

Hundreds of vendors fill Eastern Market stalls in five sheds and elsewhere on Saturdays throughout the year in Detroit. Photo by Mary Bergin

On Saturdays, throughout the year, Detroit residents come together at Eastern Market. Located one mile northeast of the city’s downtown and just beyond Chrysler Freeway, the market covers 43 acres and consists of large, century-old sheds surrounded by dozens of storefronts. The Eastern Market is America’s largest historic public market. For sale are locally sourced seasonal produce, some of it grown on vacant lots inside the city. Along sidewalks are outdoor cooks at work, grilling chicken, kebobs and more. Covering brick buildings are edgy murals. At street corners are pop-up musicians.

Motor City Music

Detroit is a city legendary for creating and enjoying good music. Before moving to Los Angeles in 1972, Berry Gordy’s Motown Records produced 110 top ten hits here from 1961 to 1971. Today, the historic recording studios that are housed in a modest neighborhood are expanding. First comes the preservation and updating of the three West Grand Boulevard buildings where so much of the early music was recorded.

Hitsville USA tours of Motown recording studios resume in August, marking the completion of a major restoration project. Next comes construction of the Motown Museum, behind the historic studios that were inside houses on West Grand Boulevard. Architectural design sketch courtesy of Perkins+Will

Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, the Supremes, Four Tops, Temptations and many others worked magic in the humbly furnished Detroit recording studios, which will reopen for tours in August 2022.

The second phase of this $50 million Motown Museum and Hitsville USA project will add a plaza and modern building for performances, interactive exhibits and classrooms. It’s all a non-profit endeavor.

Elsewhere, hometown billionaires have a hand in uplifting modern Detroit. Quicken Loans founder Dan Gilbert and the late Mike Illich, founder of Little Caesar’s Pizza, were key to establishing The District, a vibrant, 50-block hub for dining, imbibing, theater, visual arts, music and pro sports. Anchoring the area are playing venues for four Detroit teams – the MLB Tigers, NFL Lions, NBA Pistons and the NHL Red Wings – making the area impressive enough for Detroit to host the 2024 NFL Draft.

The District spans 50 blocks and is anchored by playing venues for four Detroit pro sports teams: the MLB Tigers, NFL Lions, NBA Pistons and NHL Red Wings. VisitDetroit.com photo by Vito Palmisano

The area is walkable but also accessible by the free QLine, a 12-stop, 3.3-mile streetcar line that follows the city’s main drag of Woodward Avenue from the Detroit River to Grand Boulevard. Visitors interested in the visual history of Detroit should alight at the QLine terminus and walk a few blocks west where the Art Deco style Fisher Building designed by Albert Kahn stands across the street from the former General Motors headquarters.

QLine: Better than Uber

While traveling away from downtown Detroit on the free streetcar look to the right to see the Detroit Institute of Arts, whose 65,000 works include Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry” murals (27 paintings covering four walls) and Vincent van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait.”

In 1932, Mexican muralist Diego Rivera (1886-1957) began illustrating the Detroit Institute of Arts interior walls using the fresco technique common in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome to create a series of murals that portray the technological, and human history of Detroit. On the north wall Rivera captured all the processes related to the assembly of the motor. The blast furnace glows orange and red at extreme temperatures to make molten steel that is poured into molds to make ingots that are then milled into sheets. All the major processes related to automobile manufacturing are accurately rendered with engineering precision. Rivera wove the processes together through the use of the serpentine conveyors and assembly lines. The composition is grounded by two rows of white milling machines that stand as sentinels in the center of the wall and march into the background to the blast furnace. Photo by David DeVoss

At the center of downtown Detroit sprawls a huge sandbox called Campus Martius Park. It’s a public square that takes the form of an urban beach with lounge chairs, food, cocktails and musicians. The best time to visit is at the end of the workday when hundreds of young professionals pour out of office towers from May through October to socialize in a giant urban party.

Near Campus Martius are the ouzo and saganaki of Greektown, a historic district best known for its churches, festivals, casino action and dining, especially at Golden Fleece and Pegasus Taverna.

Walk the area on your own or book a walking or bicycle tour provided by Preservation Detroit, which could include Greektown’s architecture, public art and entertainment offerings.

What’s left? Tour a near-downtown factory that arguably earned Detroit its “Motor City” moniker. Located just two blocks from a QLine stop is the Ford Piquette Plant. It is the birthplace of the Model T, which transformed Detroit into an industrial powerhouse. Guided tours of this National Historic Landmark last 90 minutes and range in cost from $10 to $17.

The Ford Piquette Avenue Plant, north of downtown, is a National Historic Landmark and birthplace of the Model T. Volunteers give guided tours, and the building was almost demolished in the 1990s. Photo by Mary Bergin

Inside the modest building are reminders of challenge and resilience. Community support keeps the facility open. Tour guide Jack Seavitt says volunteers restored the building’s 340-some windows and then began repairing floors.

Not all jewels are bright and shiny – or quick to surface. Remember this: When Henry Ford introduced his first car, the Quadricycle, few bought it. His Detroit Automobile Company went bankrupt in 18 months. It would be four years before his new Ford Motor Company’s introduction of the Model A began to change the world.

Train Station Resurection

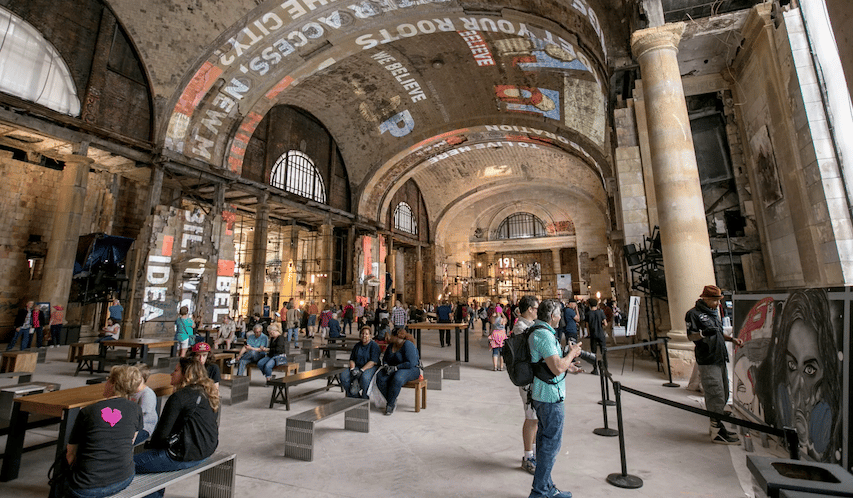

Detroit’s renaissance is not complete, but support for rehabilitating buildings and neighborhoods stays steady. Ford Motor Company leads the effort by renovating once-glorious Michigan Central Station, the city’s long-abandoned main train station, which will anchor a new, 30-acre and $950 million tech/innovation district in Corktown. Google will take a lead too, offering free classes for high schoolers and others.

Ford Motor Company paid $90 million for the right to renovate the Michigan Central Railway Station. The massive restoration should be complete by next year. Photo by freep.com

Ford is expected to finish its part of the project in 2023, turning the 1913 depot into a gathering spot that will be surrounded by new housing.![]()

Mary Bergin of Madison, Wis., is a three-time Lowell Thomas Award winner whose writing specialties include Midwest U.S. destinations.