Meters-long alphorns are a customary part of Swiss-themed festivals in New Glarus, Wis. Photo courtesy of Green County Tourism

By Mary Bergin

New Glarus, Wisconsin, is a village of 2,247 residents that takes pride in being known as “America’s Little Switzerland.” Located 30 miles southwest of Madison, the community supports a männerchor (men’s choir), kinderchor (youth choir) and jodlerklub (choir of yodelers). The mournful sound of meters-long alphorns (used long ago by the Swiss to call cattle home) is a customary part of festivals. Since 1938, annual Wilhelm Tell performances commemorate the fight to free Switzerland from Austrian rule. In the late 1960s, a Heidi Festival became an annual event. Newest is Silvesterchlausen, which features bellringers in funky costumes who yodel as the new year arrives.

My last visit to New Glarus included time at Puempel’s, a tavern lavishly decorated with Old World scenes on massive indoor murals. A foursome of laid-back women – young retirees and casually dressed – was playing cards on a Tuesday afternoon, their weekly habit for 13 years.

A Swiss immigrant family opened Puempel’s as a rooming house in 1893. Their son inherited the business, which he managed for 58 years. Today a lifelong neighbor upholds the working-class ambiance and charm. Menu specialties stay simple: Think soup, sandwiches and cheese. Always cheese.

Puempel’s Polka Poppers – hobbyist musicians from the area – sing and play accordions and banjos. Someone might keep rhythm with a washboard or other old-timey instruments at the tavern on occasional Saturday afternoons. It feels like a homey jam session, and the small group of four or five performers (who shows up depends on the week) also entertains at festivals and retirement homes.

Musicians play polkas and other feel-good tunes on some Saturday afternoons at Puempel’s, a century-old tavern in New Glarus, Wis. Photo courtesy of Green County Tourism

A leisurely stroll by others in New Glarus begins and ends at Puempel’s on Thursday nights. “The group usually walks for an hour, not too fast, so they can visit and “enjoy the sights and sounds” of their quiet, slightly hilly surroundings, Facebook explains. Passersby are welcome to join the neighborly shuffle.

I usually buy nut horns covered with a thin icing and flakey almond horns from New Glarus Bakery, just around the block from the tavern. Between the two businesses is Edelweiss Cheese; co-owner Bruce Workman is a master cheesemaker whose 180-pound wheels of Swiss Emmentaler win top American Cheese Society awards.

Order an appetizer of cheese fondue, then Geschnetzeltes (veal in a wine-mushroom-cream sauce) with rösti (sauteed potatoes) at Chalet Landhaus. Wash it down with New Glarus Brewing’s Spotted Cow, an ale only sold in Wisconsin and arguably the state’s most popular craft beer.

Drive to New Glarus with the window open during summer and listen for the tinkle of cowbells worn by grazing herds of Brown Swiss. Cows are respected members of the community and show up in municipal parades.

Chalet-style architecture dominates the downtown. Follow the trail of a dozen fiberglass cows, each unique because of artists’ embellishments.

Why here?

A Brown Swiss cow wears a bell around its neck in New Glarus, Wis. Photo courtesy of Green County Tourism

Deep devotion to Swiss and agricultural heritage exists because of the 118 people who emigrated from Switzerland’s canton of Glarus in 1845. The woods and hills of southern Wisconsin reminded them of home, which they left because of devastating crop failures and famine.

“What makes New Glarus unique is how deeply the pride in our Swiss heritage and culture runs,” says Bekah Stauffacher, president/CEO of the Swiss Center of North America, based in New Glarus. Architecture, festivals, museums and groups for singers, yodelers and card players are reminders of Swiss roots – and “all of those things tie together to make a vibrant, multilayered community.”

The Swiss Center preserves stories of immigration in the United States and Canada. Among the artifacts: thousands of Swiss postcards from 1895 to 1945, textiles, folk art, books and family genealogies. Additional artifacts fill Chalet of the Golden Fleece (an authentic Swiss chalet) and Swiss Historical Village (14 structures that illustrate pioneer life).

The quest to stay true to rural heritage and traditions surfaces in other ways too. Jass is the national card game of Switzerland, for example, and it’s played in New Glarus, but the village also hosts the annual World Euchre Championship. Jass and euchre are loosely related, trick-stealing games that originated in the same part of Europe.

Says Noreen Rueckert, director of Green County Tourism, home to New Glarus: “I once heard a Swiss native who had moved here say that New Glarus was more Swiss than Switzerland. I think it is rather unique that multiple generations are involved in carrying on Swiss traditions – from the kids in kinderchor to the retired guys in yodel club.”

Pride of Swiss heritage is instilled at an early age in New Glarus, Wis. Photo courtesy of Green County Tourism

Hamlets With Heritage

Contrary to longstanding stereotypes held by bicoastal elites, America’s Midwest is not dull, homogenous flyover country. For proof just read The American Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (Indiana University Press, 2007). It is an 1,890-page ode and explanation of history, heritage, people, traditions and quirks that define “the middle way” practiced by 12 states in the nation’s Heartland.

History Professor Andrew Cayton of Miami University in Ohio, in the book’s introductory overview, describes the Midwest as “one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse places on earth” during the early 20th century. It’s not “the land of the bland,” he writes, “but a collection of disparate communities held together, more or less, by a civic culture that transcends (or at least ignores) differences …”

A deep cultural identity requires ongoing participation and commitment from a lot of people, and such distinctiveness becomes more difficult to hold onto with the passage of time.

Here are five Midwest exceptions, hamlets that make it a priority to nurture a deep sense of heritage.

Norwegian America

Spring Grove, Minn., pop. 1,256 – Seventy miles southeast of Rochester is Minnesota’s first Norwegian settlement, in an area known as “Norwegian Ridge.” It has matured into a hub for all things Viking, from a statue of Norse explorer Leif Ericson to a Viking-style ship at the public swimming pool.

Bluff Country Artists Gallery in Spring Grove, Minn., pays attention to the area’s Norwegian roots, and wood carvings are prominent in the art for sale. Photo by Mary Bergin

The nonprofit Giants of the Earth Heritage Center teaches Norwegian traditions, crafts, baking and language to children and adults. Bluff Country Artists Gallery sells traditional baking equipment – lefse sticks, krumkake rollers – and beautifully carved furniture. A hotdish contest is part of Uffda Fest, and Syttende Mai celebrates Norwegian independence with music and a parade, but Sons of Norway organizes food and craft demos throughout the year.

Sweden on the Prairie

Lindsborg, Kansas, pop. 3,518 – The Dala horse, which has no tail, is a popular symbol of Swedish heritage; in this town (70 miles north of Wichita) is a colorful herd of 30, each painted by a local artist. Smaller versions of the Dala and other Swedish folk art are made by craftspeople at Hemslöjd, which can be toured.

Swedish folk art, including Dala horses, is made by craftspeople at Hemslöjd, a little factory and gift shop that can be toured in Lindsborg, Kansas. Photo by Mary Bergin

Watch Swedish folk dancing or sign up for a class to participate. In Heritage Square is a pavilion that Sweden erected for the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, and it is open to visitors. An overnight at the Dröm Sött Inn comes with an immersion in homey Swedish décor and dining: Think Swedish rye, Swedish meatballs, lingonberries for breakfast.

Germany in the Heartland

Hermann, Mo., pop. 2,170 – German immigrants thought this area, 80 miles west of St. Louis, resembled the Rhine Valley upon their arrival in the 1830s. The wine country here is older than California’s Napa Valley and a trail of six family-owned wineries remains a big tourist draw. Imbibe at the rural vineyards of Adam Puchta Winery (around since 1855) or an open-air beer/wine patio downtown near the Missouri River.

The Hermann Wurst Haus produces 62 kinds of German sausage in Missouri. Photo by Mary Bergin

In the historic district of 150-some buildings are museums, the 1878 Concert Hall and Barrel (the oldest tavern west of the Mississippi River) and Hermann Wurst Haus, where in-house sausage making results in 62 products that include Blutwurst (blood sausage) and Schwartenmagen (head cheese). Some of these sausages, such as the sweet bologna, win international awards.

Denmark Dreams

Elk Horn, Iowa, pop. 595 – Danish filmmakers in 2013 did a one-hour documentary about this tranquil, out-of-the-way village, 80 miles west of Des Moines and the nation’s largest rural Danish settlement. Inside the Museum of Danish America is the late Victor Borge’s first piano, and the 30-acre museum park is named after landscape architect Jens Jensen.

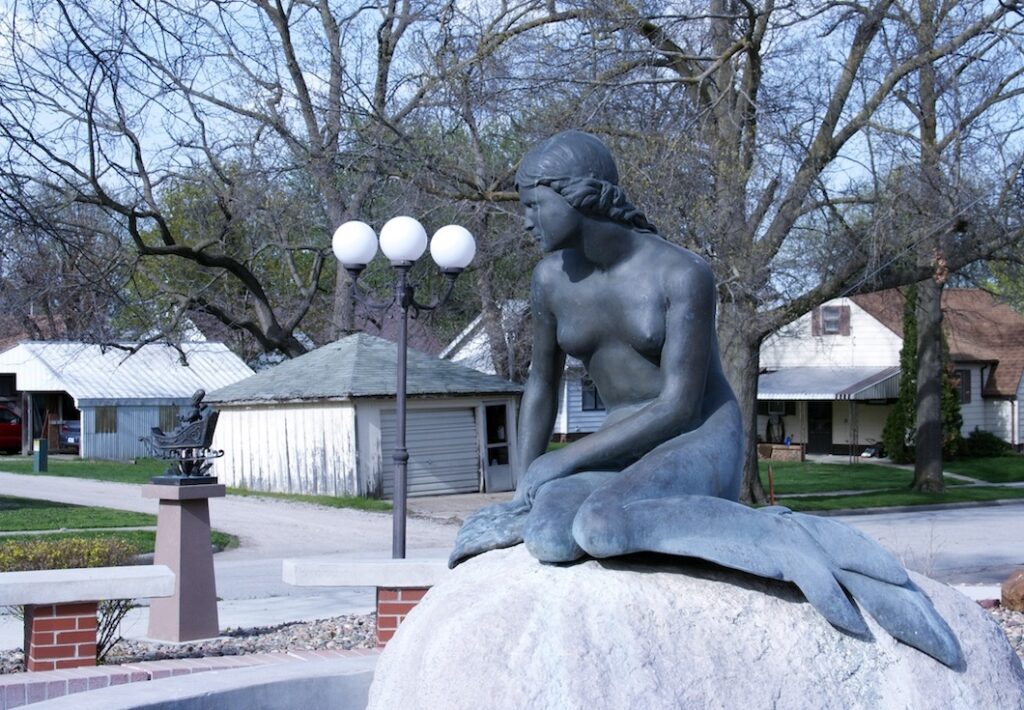

Inside the Hans Christian Andersen Sculpture Garden, north of Elk Horn, Iowa, is a replica of Denmark’s Little Mermaid. Photo by Mary Bergin

Look for the town’s welcome center inside a 60-foot-tall, imported 1848 windmill. Three miles north is a Little Mermaid replica at the Hans Christian Andersen Sculpture Garden. Tivoli and Jule festivals bring out traditional Danish attire, dancing and foods.

Luxembourg’s Midwest Home

Belgium, Wis., pop. 2,427 – Thirty miles north of Milwaukee is the Luxembourg American Cultural Society, a museum (inside an 1872 stone barn), genealogy center and headquarters for cultural programing that opened in 2009.

The procession of sheep and people in traditional herdsman’s attire is a tradition during Luxembourg Fest Week in Belgium, Wis. Photo courtesy of the Luxembourg American Cultural Society

The Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg showed up for the dedication, and former prime ministers have visited too. No other cultural institute nationwide is trusted by Luxembourg leadership to assist with dual-citizenship requests, and more than 3,000 families have been helped.

One family surname is honored during Luxembourg Fest Week, which turns the annual event into an international family reunion. Most unusual is the eating of treipen – a sausage with equal parts meat, veggies and pig blood; the festival goes through 200 pounds in two days.

Why call the village “Belgium”? The name “Luxembourg” already was taken by a Wisconsin community that is 80 miles away.![]()

Mary Bergin’s sixth book is Small-Town Wisconsin: Fun, Surprising and Exceptional Road Trips (2023, Globe Pequot). She lives in Madison, Wis. Recently, she also wrote about ocean-going condominiums and the rebirth of America’s Motor City, Detroit.