Much like the Eiffel Tower in Paris or the Parthenon in Athens, Hagia Sophia is a long-enduring symbol of cosmopolitan Istanbul. Built as a Christian basilica 1,500 years ago. it has served for centuries as a landmark for both Orthodox Christians and Muslims. Byzantine Emperor Constantine commissioned the first Hagia Sophia in 360 A.D. when Istanbul was called Constantinople. The structure burned in 404 and was reconstructed 11 years later by Emperor Theodosius. One century later the Greek Orthodox basilica burned to the ground a second time in a revolt against Emperor Justinian. Justinian rebuilt the massive basilica in 537 with marble from Syria, bricks from North Africa and 104 columns from Egypt and the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.

By Nancy Wigston

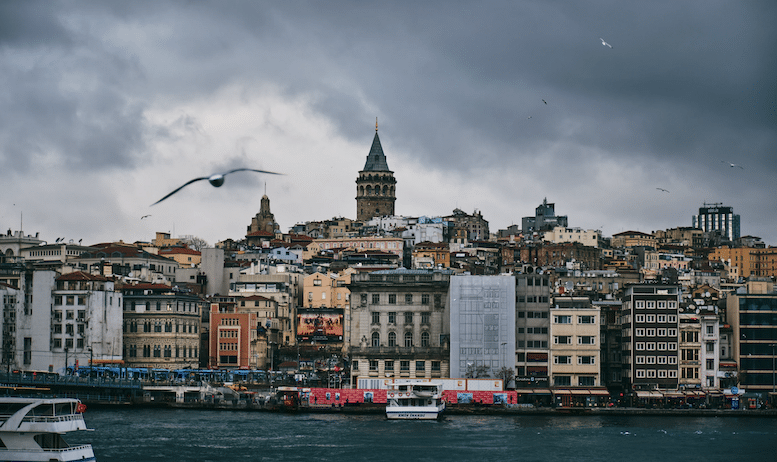

Istanbul, as the song goes, was once Constantinople. A jewel of a city straddling Asia and Europe, its sheltered harbor overlooks the narrow Bosphorus Strait, which connects the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara. Witness to the rise and fall of great empires—Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman—the Turkish capitol has long been a prize of empire.

Two centuries ago, Napoleon remarked that he would gladly have shared Turkey with Russia, if not for Istanbul, “an Empire in itself, the real keystone of power, for he who possesses it may rule the world.”

In recent decades, Turkey has become an increasingly popular tourist destination. Near-intact Roman ruins at Ephesus draw lovers of the classical world as well as Christians who light candles at the house where Christ’s mother Mary fled with the Apostle John after the Crucifixion. In Central Turkey, the towns of Cappadocia—mentioned in the works of Herodotus, the Book of Acts and the Talmud—dazzle with cone-shaped rock formations atop caves that sheltered early Christians. In south-east Anatolia, the UNESCO protectorate of Mardin is an ecclesiastical center shared by Assyrian, Armenian and Chaldean faiths. A 5th century Syrian Orthodox monastery outside town–oldest in the world–was a temple for sun worshippers in 2000 BC.

Adjacent to the modern Turkish town of Izmir, Ephesus was a major Roman trading and administrative center. Mary the mother of Jesus lived here after the Crucifixion. John the Apostle is buried here. The Apostle Paul’s letter to the Ephesians is one of the books in the New Testament.

Istanbul, the gateway to Turkey, inspires varying emotions. Lord Byron rhapsodized about its sensuality. Mark Twain harrumphed that Turkish dress was a “wild masquerade.” Mystery writer Agatha Christie put her thoughts on paper. In the 1930s, in Room 411 at the Pera Palace Hotel, she penned Murder on the Orient Express. You can stay in her room if you want.

Turkey’s latest passion are addictive TV dramas called dizis, that are popular with fans in 145 countries. Dizi, which means “series” in Turkish, rival 1980s hits like Dallas, Falcon Crest and Dynasty with gorgeous stars, high production values and intriguing plots. Shows subtitled in English are available on Netflix, YouTube and a host of other streaming services.

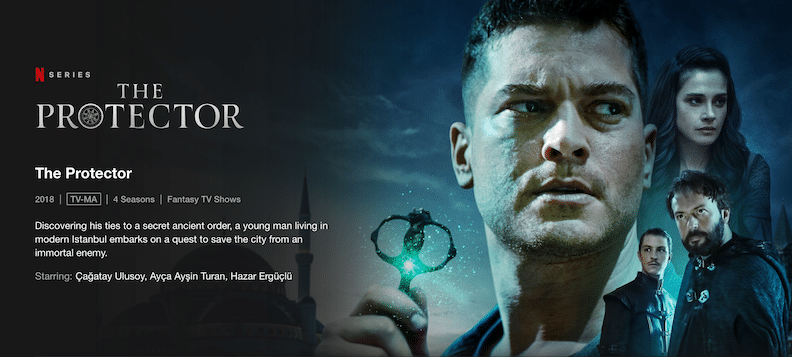

Consider The Protector, a Top Ten dizi hit that follows the exploits of a muscular, poor but ambitious young man working for his adoptive father in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar. When a woman enters their antique store, enquiring about a “talismanic Ottoman shirt,” his father denies its existence, but his son, Hakan, has seen it. What gives? Shocked to learn he has inherited the mantle of The Protector, Hakan soon dons that magic shirt to fight the Immortals, dark forces whose triumph would mean the collapse of civilised Istanbul. Holy Napoleon!

Whether action-packed or smouldering with romantic yearnings, dizi story arcs last several seasons and episodes can be two hours long, keeping fans glued to screens in the Americas, Asia, The Balkans, The Middle East, Europe, and the United Kingdom. Turkish dizis have few rivals in other countries, apart from the States or the UK. Mythical superheroes, weird archeologists, fur-clad 13th century tribal nomads on horseback—all attract keen followers, as do contemporary issues–gang rape, homelessness, money laundering. There are some taboos in the shows—there’s little explicit sex—but more taboos are broken in dizis than in state-controlled shows in strict Muslim countries.

Whether action-packed or smouldering with romantic yearnings, dizi story arcs last several seasons and episodes can be two hours long, keeping fans glued to screens in the Americas, Asia, The Balkans, The Middle East, Europe, and the United Kingdom. Turkish dizis have few rivals in other countries, apart from the States or the UK. Mythical superheroes, weird archeologists, fur-clad 13th century tribal nomads on horseback—all attract keen followers, as do contemporary issues–gang rape, homelessness, money laundering. There are some taboos in the shows—there’s little explicit sex—but more taboos are broken in dizis than in state-controlled shows in strict Muslim countries.

“I was smitten from the start,” says Cairo-born Brit Vivian O’Keefe of Kurt Serit and Sura, an epic love story based on actual family history. Kurt Serit, an army officer with Turkish roots, falls for Sura, a Russian noble woman, during the 1917 revolution. Besides the exciting plot, the main attraction is actor Kivanc Tatlitug as Kurt Serit. Tall, blonde and chiselled, the former model is fondly nicknamed the “Turkish Brad Pitt.” Since being smitten, Vivian has twice travelled with fellow fans to Turkey and now manages the Kivanc Facebook page with its 138,000 followers. (FB fan pages like the Turkish Drama Appreciation Group, or TDAG, are members-only.)

Londoner Poppy Akhtar discovered Turkish dramas in 2017 while suffering from a cold in her Beijing hotel. A self-described “off the beaten track” traveller with roots in Pakistan and London, Poppy works as a consultant in broadcast technology management. A lover of writers Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy and Leo Tolstoy, Poppy admires dizis for powerful storytelling and dialogue that “resonates, touches your heart.”

Londoner Poppy Akhtar discovered Turkish dramas in 2017 while suffering from a cold in her Beijing hotel. A self-described “off the beaten track” traveller with roots in Pakistan and London, Poppy works as a consultant in broadcast technology management. A lover of writers Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy and Leo Tolstoy, Poppy admires dizis for powerful storytelling and dialogue that “resonates, touches your heart.”

Besides “lessons in human fallibility” dizis portray “love of family, religion and culture.” Hearing Arabic phrases like Inshalla (God willing) makes Poppy feel like she’s coming home. When the subject of a dowry arose in her current favorite show, Hirjai (“Fickle”), a dizi set in the gorgeous old city of Mardin, she posted a blog explaining nuances around the custom that “Westerners don’t get.” Another plus: “Men are respectful. If I want to see romping, I’ll go to Bond or action movies.”

“Many North Americans run platforms that organize meet and greets with Turkish actors when they come to the States,” Akhtar confides. When followers of the website North America Ten learned that a dizi star was visiting Orlando, fans drove hours from their homes in other states to say hello. Dizi fandom is a clubbish and very connected world.

Little wonder that a cottage travel industry has emerged, as fans fly to Istanbul to visit film locations in the gritty and beautiful neighborhoods featured in ninety per cent of dizis. In The Protector’s opening scenes, Hakan bounds through the 560-year old Grand Bazaar, arriving at his father’s antique shop. Viewers who fly to Istanbul can enjoy a tour of the bazaar, home to some three thousand retailers selling everything from gold, jewelry, watches, ceramics, and, not least, carpets. Another shopping must-see is the Spice Bazaar, which dates from 1660 AD. Eighty-five vendors sell spices, sweets and caviar that invite further exploration of Turkish cuisine.

Little wonder that a cottage travel industry has emerged, as fans fly to Istanbul to visit film locations in the gritty and beautiful neighborhoods featured in ninety per cent of dizis. In The Protector’s opening scenes, Hakan bounds through the 560-year old Grand Bazaar, arriving at his father’s antique shop. Viewers who fly to Istanbul can enjoy a tour of the bazaar, home to some three thousand retailers selling everything from gold, jewelry, watches, ceramics, and, not least, carpets. Another shopping must-see is the Spice Bazaar, which dates from 1660 AD. Eighty-five vendors sell spices, sweets and caviar that invite further exploration of Turkish cuisine.

Since this is Istanbul, a carpet sale figures in The Protector’s opening episode. Delivering the rug his father has sold to an American tourist, Hakan arrives at the woman’s hotel, where, at her request, they indulge in a quickie. Such special delivery service is far more unusual than the sale of a carpet in Istanbul, where dealers call out to customers in multiple languages on almost every block.

A crossroads city, Istanbul is savvy about catering to travellers’ tastes. Hand-knotted carpets, silk carpets, kilims, carpets dyed warm ochres and blues–the quantity and variety of Turkish rugs tend to be better value than those made in Iran or Afghanistan, perhaps due to their easy accessibility.

A crossroads city, Istanbul is savvy about catering to travellers’ tastes. Hand-knotted carpets, silk carpets, kilims, carpets dyed warm ochres and blues–the quantity and variety of Turkish rugs tend to be better value than those made in Iran or Afghanistan, perhaps due to their easy accessibility.

Dizi fans and regular tourists alike visit Istanbul’s Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, where rare carpets are displayed like Rembrandts. Pause for a break in the excellent museum café, sipping divine Turkish coffee or tea delivered on silver trays, fresh sweets on the side. “Coffee? Tea?” is the commonest offer to a guest on Turkish dizis, and this museum café offers the ideal opportunity to indulge or buy some to take home.

Besides carpets and the Grand Bazaar, The Protector also spotlights the Hagia Sophia, a wonder of the world. Early on in episode one, an immensely rich man (and a dreaded Immortal) is seen coveting the structure, honing his company’s bid for the contract to refurbish and therefore gain control of this Istanbul gem. He even quotes Napoleon.

For a thousand years the astonishing Hagia Sophia was the largest cathedral in Christendom. Built in the 7th century by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, it was briefly Roman Catholic under the Crusaders, then Eastern Orthodox again, until becoming a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of 1453.

Reformist president Kemal Ataturk (who also gave women the vote) declared it a museum in 1935 to reflect Istanbul’s cultural heritage. The current government changed the landmark back to a mosque last summer, but the interior, with its Islamic calligraphy, Christian frescoes, chandeliers and black-and-gold color scheme has not changed. Tourists are welcome.

Another city landmark, the Sultan Ahmet or Blue Mosque, is neither blue nor does it figure in a dizi, except as part of the cityscape. It is, however, 1,300 hundred years old. On entering, visitors discover a world of tiled walls of Bosphorus Blue, (an ancient sign of wealth), tulip designs (tulips originated here and in Persia), ceiling frescoes, artists’ panels, carpets, dim lights.

Remove your shoes. Legend tells us that before marrying, a Turkish girl wove a carpet of her own design, the only thing she took into her marriage. So, as the Turkish folk saying goes, please remove your shoes, or you walk on her life.

Equally famous is Topkapi Palace or Cannon Gate, home in the 15th and 16th centuries to a succession of Ottoman Sultans. At the urging of Suleiman the Magnificent, they started to move to the Jewish and Christian Ortakoy district in the 16h century, occupying mansions and palaces overlooking the Bosphorus, rather like the ultra-rich in today’s dizis.

Equally famous is Topkapi Palace or Cannon Gate, home in the 15th and 16th centuries to a succession of Ottoman Sultans. At the urging of Suleiman the Magnificent, they started to move to the Jewish and Christian Ortakoy district in the 16h century, occupying mansions and palaces overlooking the Bosphorus, rather like the ultra-rich in today’s dizis.

Originally heads of government not only held court in this complex of buildings, but their wives and children lived in harem or family areas, protected by eunuch bodyguards. Jules Dassin’s eponymous 1964 heist film centered on the theft of the invaluable palace jewels on view today in the Imperial Treasury. Most dazzling: the gold Topkapi dagger, studded with emeralds, and the 86-carat, pear-shaped Spoonmaker’s Diamond–both are well-guarded by police. When singer Michael Jackson requested that the Spoonmaker’s Diamond be featured in a music video, the answer was “no.”

Adjacent to the old imperial walls, close to the 4th century Saint Irene Church, is Karakol, a terraced restaurant that was once an Ottoman guard post. Under the shady umbrellas, in a quiet garden with views of the Bosphorus, Karakol serves an array of mezes (tapas), excellent salads, beef barbecue, lamb, and kebabs, and for dessert, truly excellent baklava with clotted cream. Turkish cuisine incorporates a subtle blend of spices, without the fire of South Asian fare. Italian restaurants are also popular—and very good—and if you’re craving American gastro fare, you can find that too.

Informal fish restaurants line the underside of Galata Bridge, connecting Europe and Asia. Fresh-caught mackerel on lettuce, spritzed with lemon and slapped on a bun (balik ekmek) is an inexpensive and delicious riverside snack. Cheap versus pricey fare plays a role in a dizi lover’s quarrel. When the rich girl refuses a liver kebab wrapped in soft pita that a poor boy offers her, he points out that he tried sushi for her. With a sigh and a grimace she reluctantly agrees to a bite.

Streets snacks are plentiful and include fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice, grilled corn, roasted chestnuts, cashews and bagel-shaped rolls called simit which are crusted with sesame seeds. Turkish coffee is always fortifying, tea comes in tiny glasses. Dizi characters are constantly sipping, whether they meet in cafes for romantic trysts or to plot their next cunning moves.

The dizi image of Istanbul shows a city of cafés, clubs and cosmopolitanism, where the action frequently occurs near the Galata Tower or in the beautiful old mansions on the Princes’ Islands in the Bosphorus. Women actors tend to be chic, their clothes less a political statement than a reflection that audiences prefer not to see women wearing hijabs in sultry romances, though abayas are common enough on city streets.

Galata Tower as seen from the Asian side of the Bosphorus Strait. It was the tallest building in Istanbul at 219.5 ft when it was built in 1348. Photo by Halil Ibrahim Cetinkaya

An interesting exception occurs in Ethos (streaming on Netflix), where the central character, a naïve but fascinating, headscarf-wearing young woman, encounters liberal, modern Istanbul via her housecleaning job. All the women characters—including two psychiatrists—are having problems in their personal lives, and one, ironically, plays a popular dizi actress constantly besieged by fans wanting selfies as she enjoys a glass of wine with friends. Further dizi plots move outside Istanbul, where women’s attire becomes more modest and some very old men even wear turbans.

Saying good-bye to Istanbul is always difficult, and fans frequently travel to other dizi locations for a further week of sightseeing. For a memorable send-off from the city, attend the Sufi religious dance known as the Whirling Dervishes. These occur all over Turkey, and an evening at Efendi House near Istanbul’s Blue Mosque features a group of followers of the 13th century mystic poet/philosopher Rumi. After some introductory drumming and singing, tall-hatted men in white long-skirted robes form a circle to perform their silent, mesmerizing, prayerful dance, one hand pointing to heaven, the other to earth.

A celebratory good-bye meal at one of many restaurants on the Sea of Marmara begins with hand-selecting sea bass, mackerel or some other fish from a cooler. The waiter then brings a scale to weigh and price your choices. A selection of meze arrives as a starter: white anchovies, fresh grape leaves stuffed with rice and beef, octopus, and anchovy-wrapped olives.

A celebratory good-bye meal at one of many restaurants on the Sea of Marmara begins with hand-selecting sea bass, mackerel or some other fish from a cooler. The waiter then brings a scale to weigh and price your choices. A selection of meze arrives as a starter: white anchovies, fresh grape leaves stuffed with rice and beef, octopus, and anchovy-wrapped olives.

During our final meal, the sun set, as boats in the harbor clinked softly. Returning to our hotel included a detour to enjoy the panoramic views of old Istanbul from the rooftop of the Pierre Loti Hotel.

Not every dizi fan has been to Turkey. Harison (pronounced Har-i-soon) Yusoff lives in Kuala Lumpur, and started binge watching Turkish TV series in March 2020 when a Covid 19 lockdown was implemented. “My son,” says Harison, “introduced me to Netflix and I was excited about the options to explore more global entertainment as opposed to the usual American and British offerings. I tried Korean, Turkish, French, Russian, Polish and Scandinavian series and I have to admit that Turkish series especially their period dramas are my favourite.”

Like every fan, she has her favorites–Resurrection, the Muslim Game of Thrones about Erteğrul, the tribal leader whose son, Osman I, founded the Ottoman Empire, and Filinta Mustafa, a 19th century Istanbul detective series. “I love both these shows because of their strong characters and references to the impressive Ottoman Empire and its history,” she says. “Both series have elements of politics, war, economic turmoil, mystery, treachery and, most importantly, love and compassion.”

Istanbul’s Sultanahmet neighborhood has many Ottoman era buildings that are easily identified by their distinctive windows.

Harison confesses she became “so emotionally connected” to Resurrection that when the five-season run finished she suffered withdrawal symptoms.

In addition to historical epics she has watched numerous modern dizis, including Kara Para Aşk (Black Money Love), a series that combines east and west, much like Istanbul itself. In this series characters jet to Italy or the U.S. and listen to car radios playing Ray Charles and Leonard Cohen. The female lead’s favorite film is Roman Holiday.

Like all lovers of dizis, Harison feels “transported into the setting. I have never been to Turkey and watching these series peaks my interest. Istanbul, Konya (an 8000-year-old city, home to13th century poet/philosopher Rumi) and Antalya (Turkey’s Mediterranean “Riviera”) will be the first destinations I visit after the pandemic dies down.”

Like Vivian, who has learned a few Turkish phrases by osmosis, and Poppy, who started a language course despite the fact Turkish relates only to Finnish and Hungarian, Harison has picked up a few Turkish phrases. “Instead of Happy Birthday,” she smiles, “I wish friends and loved ones, iyi ki doğdun.”

Nancy Wigston is an award-winning travel writer whose previous work for the East West News Service includes stories on Buenos Aires, Uruguay, Chile’s Atacama Desert and Northern Argentina.