The Northern Lights, also known as aurora borealis, result from electrically charged particles from the sun traveling through space at around 300 miles a second smashing into the earth’s upper atmosphere. These geomagnetic solar storms are visible on clear, dark nights at the magnetic North and South poles. When charged particles from the sun hit atoms and molecules in our atmosphere 60 miles above the earth they turn white, green, pink, blue or purple and appear to dance. The most common color of the aurora is green. It is caused by oxygen molecules. Nitrogen produces a blur or purple hue. To the naked eye the northern lights can seem like swirling white clouds. If you want to take home a photo like the one above you’ll need more than a cell phone. A good quality camera with a zoom lens will reveal the colors. Photo courtest of Pixabay.

It’s 1:00 am under a brooding Alaska sky in February. The temperature’s a few degrees above zero here in Wiseman and there’s no sign of the aurora borealis. I wander back into the pioneer cabin where the others in my party are waiting around for the northern lights to show.

Inside, Jack Reakoff holds forth about how to hunt, slice and transport the hides and carcasses of various large Alaskan mammals. He describes the cutting kit he takes along on hunting trips, and mimes slicing through his own ribs as a demo. He’s even brought laminated, full-color sheets showing himself and his wife posing with their kills and pictures of the chunks of meat these animals become.

Reakoff moved to Alaska as a child with his homesteader parents and has lived here for more than fifty years. He segues from the best cuts of moose and bear to his upcoming gig training Special Forces how to safely cross frozen rivers.

“What do you think the most dangerous thing here is?” he asks, peering around the pioneer cabin at my group, a ball of energy despite the hour. “Bears? Moose? No, falling through the ice. Getting wet in cold weather.”

The aurora never shows on my second night in Alaska. Still, after a couple of hours with Jack, I’m gripped by the spirit of Alaska and the self-sufficiency necessary to live here.

The tour

I found myself in Wiseman as part of the Arctic Circle Auroral Fly/Drive Adventure operated by Northern Alaska Tour Company. My group left Fairbanks in a northbound bus on a Monday morning. The plan was to stop at a few scenic places along the way, crossing the Arctic Circle and continuing to the settlement of Coldfoot for the night. We’d stay at an inn, go aurora hunting, then fly back to Fairbanks on small planes the next day.

The tour runs during the long Aurora season, from August 21 to April 21, but winter is the best time to go. We traveled on some of Alaska’s most famous highways—the Steese, Elliott and Dalton—when they were covered with snow and ice. The Dalton is especially notorious, 414 miles, mostly gravel. It stretches from Livengood to Deadhorse, near the oil fields of Prudhoe Bay in northern Alaska. It was built in the 1970s when the 800-mile Trans-Alaska pipeline was put in, which will be our companion running along the road for much of our trip.

Reality TV fans will be familiar with the remote Dalton Highway from seasons three to six of Ice Road Truckers. Ice over gravel over permafrost makes for a bumpy ride. By the end of the day, my confused Fitbit will have logged 12,000 steps, mostly from sitting.

Before leaving Fairbanks, our bus stops at a Safeway so people can load up on snacks, coffee and other necessities. There are no Starbucks on the Dalton Highway. We’re promised real Alaskan outhouses and, if we can hold it that long, one deluxe heated restroom at the Yukon River stop.

Our guide and driver is Aaron Marlow, an intriguing young fellow originally from Battleground, Washington. He’s been a wildland firefighter and a photojournalist covering the Black Lives Matter movement and the art scene in Los Angeles. He came to Alaska a year or so ago to work at a top dog mushing kennel, where he lived in what Alaskans call a “dry cabin”—an off the grid shack with no running water, and often no electricity. Now he’s studying business at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, researching economics in rural Alaskan villages.

Somehow he manages to maneuver a giant bus over ice while regaling us with tales of Alaska’s history, flora and fauna.

Trading post and Yukon River stops

As we drive north, Marlow points out the thermometer in the front of the bus. It reads 14° F (-10 °C). “We’re having a bit of a heat wave right now,” he says. Temperatures are likely to be below zero this time of year. Coldfoot once clocked -82 °F (-63 °C). Temperatures change fast in the Tanana Valley and Marlow encourages us to keep an eye on the thermometer.

“You can almost see it going down every second in some areas,” he says. Winter is the proving ground for young workers, a refrain I’ll hear several times over the next day. “If you work up here for a year or two there are plenty of people in Antarctica looking to hire you,” Marlow tells us. Despite the heat wave, my toes are frozen even on the bus. I don’t expect Antarctica to be calling me anytime soon.

Our first stop is a trading post, the Wildwood General Store, which is closed. The tour company bought it from the Carlsons, a homesteading family who used to run it, along with their 40 adopted children, Marlow says. Which I suspect is an exaggeration. One of the children started the whole trading post idea by opening a lemonade stand to serve Dalton Highway truckers. I’m guessing in summer. Snow is piled high around the trading post, homesteading cabin, outhouses and famous lemonade stand. We experience our first trip to an unheated Alaskan outhouse.

It’s a few more hours before a longer stop, this time at the Yukon River. The Yukon contains the fifth largest volume of water of any river in the world, and is vital to Alaska and Canada, especially for indigenous people. We stop at Yukon River Camp, a low brown building which promises food, lodging, fuel and gifts. There won’t be more fuel until Coldfoot, another 118 miles.

Kings of the Road. North of the Arctric Circle in Alaska, truckers keep the economy moving. Theirs is a difficult job and they are well compensated for their efforts. Photo by Teresa Bergen

Fortunately, everybody packed a lunch or stocked up at Safeway, because the café kitchen is closed. The proprietor, a Wyoming transplant, welcomes us to come in and sit at tables, use the microwave and the much-hyped heated bathrooms (toasty!) and supplement our meals with bags of chips. Signs in several Asian languages, and a sign in the bathroom that discourages squatting atop toilets, suggest many international tourists.

After lunch, Marlow leads us outside, past a sign that says “Do Not Enter. Barge Traffic Only” and onto the frozen Yukon River. We see the pipeline up close, at 48 inches in diameter, it’s big enough around to sit inside. Since 1977, more than 18 billion gallons of oil have flowed through the pipeline. But at negative five degrees, as I pull my neck gaiter up over my face reddening with pre-frostbite, Marlow’s Alaska factoids fail to seep into my brain. My glasses ice over and I manage to trip and fall over a pile of snow that should have been perfectly visible. Despite all the people I meet on this trip north expounding on the lure of Arctic life, I’m happy this is a short visit.

Arctic flora and fauna

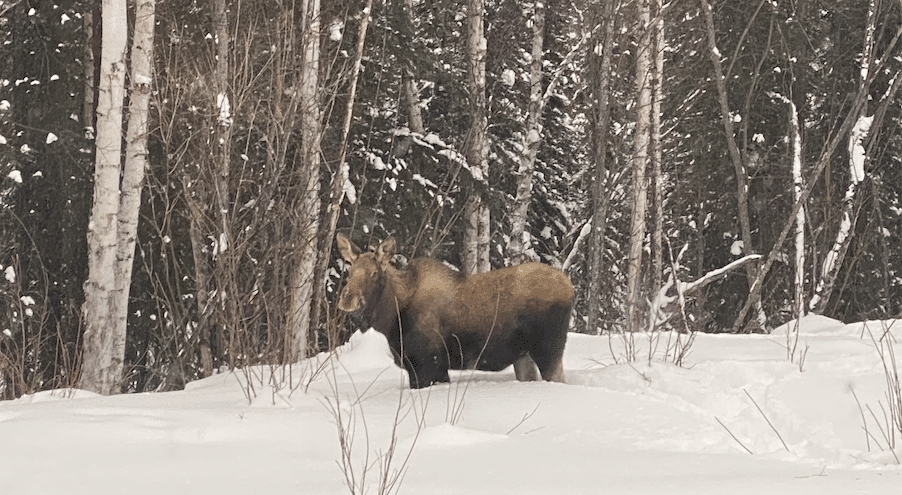

Our biggest wildlife sighting comes early in the trip. We see a moose by the road, up to her abdomen in snow. When snow piles up this high, the moose get extra cranky. They sometimes trample people and dogs to death just because they’re annoyed. Moose move silently through forests, and are known for their hearing. Native Alaskan Athabascan people never say they’re going moose hunting, Marlow tells us, lest a moose overhear.

Mostly what we see out the window is a lot of ice, snow, mountains and trees, and occasionally, a truck or tour van. Marlow keeps in touch with other traffic on a CB radio. We later learn that truck traffic is sparse because an accident a ways north has closed the road to trucks. Marlow entertains us with details of Alaska wildlife, speaking slowly. His voice fades away on steeper or icier spots where he needs to concentrate, or for brief CB chats. Then he calmly resumes his stories.

“Hey, human, what are you looking at. You think I’m a deer or a caribou? I’m a moose and I hate people. One of my uncles ended up as jerky and a blanket. I advise you to back up and leave. I can charge through this snow faster than you can blink. Even tour buses yield to me.” Photo by Teresa Bergen

We learn that black spruce, spindly specimens reminiscent of Charlie Brown’s Christmas tree, grow on permafrost. They may be old but they never get tall because they only have a foot or two of soil to root into. Native Alaskans believe the white spruce, which grows taller, is a guardian spirit, and will sometimes shelter beneath one when things get dicey. Marlow tells us of summer’s bounty, hard to believe on such a white day: blueberries, rhubarb, chokecherries, watermelon berries, cranberries, cloudberries, crowberries.

The animals hidden in the snowy expanse outside the bus window especially capture my imagination. The Arctic ground squirrel can drop its body temp to -28, lower than any mammal on the planet, and creates natural antifreeze in its blood. While it hibernates, its heart rate slows to five or six beats per minute and nonvital brain functions shut down. It has to wake up every week or two to reintroduce blood flow to the brain, then returns to hibernation mode. The only amphibian in the area is the Arctic tree frog. It spends the winter frozen, then thaws out and hops off in the summer.

Mesmerized by miles of whiteness, it’s hard to believe anything is living out here. Then suddenly a half dozen white ptarmigan birds lift off, like the snow taking shape, coming to life and flying away. How many others are camouflaged by the snow?

Northern Alaska isn’t really a place for humans. At least, not most humans. Alaska has the highest per capita missing person rate, Marlow tells us. At thaw time, troopers search for bodies. “Alaska’s a place of great beauty and great danger,” he says. “It’s not very forgiving if you make mistakes.”

Crossing the Arctic Circle

It’s almost dark by the time we get to the Arctic Circle, that ring around the globe known for 24 hours daylight in summer and no sunrise in winter. Another tour group has forgotten its red carpet, which lies on the ground, frozen. Marlow unrolls his own fresh red carpet in front of a sign proclaiming we’ve reached the Arctic Circle, and we all take turns standing on it, getting our pictures taken. It’s about zero degrees and windy, fingers freezing as we try to work our cameras. Marlow drags out thermoses of hot water and makes coffee, tea, hot chocolate and cider. We have the chance to use the chilliest outhouse yet.

Most of the people on our bus have signed up for a roundtrip tour. This is their end point. They’ll spend the next eight or so hours driving back to Fairbanks, maybe stopping for aurora viewing. Eight of us are continuing north. Connor Olson, an enthusiastic transplant from Michigan, loads us into a van. He works for Coldfoot Camp, which partners with Northern Alaska Tours for the next section of our journey. As we drive into the darkness on the frozen road, Olson tells us about his four years so far in Alaska, and what it’s like to live in a place with a population of twenty. On the more treacherous ascents and descents, he asks us to hold our questions and be quiet for a few minutes.

Coldfoot Camp

The main features of Coldfoot Camp turn out to be a truck stop café and the Slate Creek Inn, which doesn’t look much like a hotel at all. We also find the trucks that couldn’t continue south. About thirty glossy eighteen-wheelers idle in the vast parking lot. In cold weather, trucks stay on all night. If drivers turn off their engines, they won’t be able to restart them.

Over the course of the night and the next day, we hear versions of the Coldfoot origin story several times. Slate Creek Camp started back in 1898 with, of course, gold. When some prospectors got “cold feet” about the harsh winter, the hardier folks who stayed changed the village’s name to Coldfoot. In its gold heyday, Coldfoot included seven saloons, a gambling hall, a post office and ten prostitutes, some of whom are commemorated in the names of local creeks. By 1912, prospectors decided that Wiseman, thirteen miles north, was a better bet. They dismantled Coldfoot’s buildings and brought them to Wiseman for construction or firewood. Coldfoot rose again in the 1970s when up to 300 people lived in the camp while building the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Then in 1981, Iditarod champion Dick Mackey hauled an old school bus up to Coldfoot and sold hamburgers to truckers—a food cart before its time. The truckers, enthusiastic about getting a hot meal in the middle of nowhere, donated wooden packing crates used to haul pipeline insulation and, on their time off, helped build a permanent structure. Voila, the café.

According to my Coldfoot sources, several people previously held the government-issued concession to sell fuel and food here. But they kept going broke. Adding tourism to the mix is what’s keeping Coldfoot afloat these days. Guided winter adventures include aurora viewing, snowshoeing and dogsledding. The Arctic Mountain Safari takes visitors even farther north into the tundra, where they hope to see caribou, musk ox and other wildlife.

If you’re used to luxury hotels, Slate Creek Inn might come as a shock. The building is made from old trailers used to house pipeline workers. When we arrive, the temperature is a few degrees above zero. We enter the warm inn to a heavy diesel smell—the whole camp is run on a generator. There’s a large, plain common area and narrow hallways leading to small rooms with twin beds. Rooms have been refurbished since oil camp days so that each room has a private shower and toilet. But they haven’t gone overboard in redecorating. In the middle of nowhere, you can charge $219 to $249 a night, depending on the season, and not bother to paint a particle board wall. People mostly are grateful for heat and a bed when the nearest hotel is more than 100 miles away. The mattress turns out to be extremely comfortable, and after a night of failed aurora viewing, I sleep great.

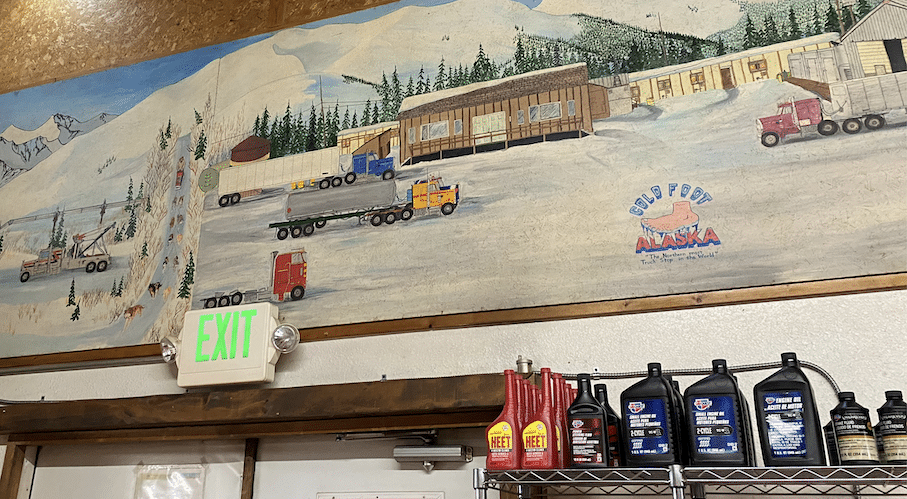

Coldfoot celebrates its status as the northernmost truck stop in the world with a mural dedicated to – who else? – truckers. Beer and bourbon are popular items for sale. So is anti freeze. Photo by Teresa Bergen

Trucker cafe

The trucker café is divided into the restaurant section and the Frozen Foot Saloon, Alaska’s northernmost bar. The night we arrive, truckers take up every barstool. The café is open 24 hours and serves food from five AM until midnight, but people are welcome to just hang out there without ordering. The menu is bigger than I’d expect, considering everything has to be trucked or flown in. I’m especially surprised to find veggie burgers on the menu and good salad greens. Murals depicting the lives of Alaskan truckers ring the top of the café walls.

Near the register, a dozen or so gift certificates hang on a metal tree. When one trucker helps another out, he might be rewarded with twenty dollars to spend at the café—a nice surprise when he comes up to pay for dinner or lunch. It’s another reminder of how much people have to rely on each other way out on the remote Dalton Highway.

Coldfoot tours

It’s a busy morning for winter when I awaken in Coldfoot Camp. The popular dog sledding tour is sold out, so I find myself on a snowshoe expedition led by two young guides, Meghan White and Mitch Weiss. About ten of us wrestle our snow boots into snowshoes and set out on a trail. The day is beautiful, sunny and clear, and we can see the southern edge of the Brooks Range.

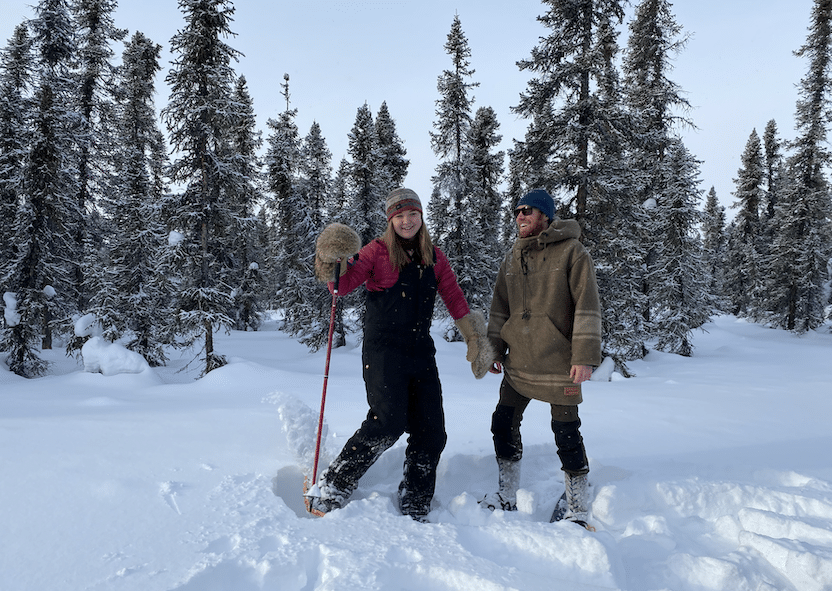

Meghan White and Mitch Weiss both left the “Lower 48” to live in Alaska. They met in Juneau and work in Coldfoot but plan to move to Fox, AK and become professional dog mushers. Photo by Teresa Bergen

Our guides look the part. Weiss wears a long camel-colored hooded tunic, made in Quebec. White has fabulous handmade mittens sewn from wolf fur, a Christmas present from Weiss. White grew up in Tennessee by the Great Smokies, the most visited national park. Now she lives right by Gates of the Arctic, the national park with the fewest visitors. She came to Alaska on summer break four years ago at age 19 and wound up staying. Her first job was in Juneau at the Mendenhall Glacier, working for a rafting company as a photo girl. She climbed a tree and hung out over the rapids, taking photos to sell to the rafters. That’s where she met Weiss, who was a kayak guide for the same company. In a real Alaska story of opportunity and serendipity, the young couple moved to the town of Fox (pop. 500), north of Fairbanks, to help a Swiss dog musher. He’d torn his ACL and needed help exercising and training his dogs. With no experience, White and Weiss learned to mush, and White fell in love with the sport. Now their plan is to move back to Fox, buy their own house, get a dog team together, start their own dog mushing tour company, and eventually race in the Iditarod. White admits that Weiss wouldn’t pursue this dream on his own. “He’s more of a cat person,” she says.

Our snowshoeing expedition is peaceful, the snow glittering white. The most excitement happens when the Coldfoot dog team rips around a bend in the trail, surprising us. We jump off the trail into deep snow as the dogs swivel their heads toward us, tongues lolling goofily, eyes curious, equally surprised by our presence. They have so much spark and personality, I can see why White dreams of her own team.

Hard to say whether Alaska’s economy is more dependent on truckers or pilots like Neil Marvin. Marvin says he may end up flying for United or American someday. But for now he’s happy transporting small groups of people across some of the most beautiful country in North America. Photo by Teresa Bergen.

Flying back to Fairbanks

Our original itinerary has us flying out of Coldfoot and back to Fairbanks somewhere between eleven and four. That’s a big window. Marlow explained to me that the flight time depends on several factors, notably weather and availability of planes. Ultimately, we’re told to show up in the lobby of the Slate Creek Inn at 1:45 to be shuttled to the airport.

Sculpting a solid block into an evocative human form is a true test of artistry. Try using a chisel in sub-freezing temperatures while wearing gloves. But that’s what contestants who enter the World Ice Art Championship in Fairbanks have to do. Photo by Teresa Bergen

About thirty people are milling around the lobby by 1:30. The planes take eight passengers. Weiss has a list and is coordinating groups of people, shuttle vans and planes. It’s a bit chaotic, but my group is lucky to get on the second flight. The van drives us to tiny Coldfoot Airport where we meet our pilot, twenty-something Neil Marvin, who will fly us on a Piper Navajo. We’ve all emailed our body weights ahead of time, and our luggage was weighed before leaving Fairbanks. Marvin consults his weight chart and tells us where to sit. The biggest guys load toward the front. Four of us who are approximately the same weight are told to choose seats near the back of the plane.

As we take off, the sky is clear and we get glorious views of Coldfoot Mountain and the Brooks Range. Marvin narrates highlights over our bulky headsets. He points out dozens of frozen ponds in flatlands which he says are boggy and mosquito-ridden in summer. We pass over the frozen Yukon River, which just yesterday we walked on. From the air, you can see how curvy it is. Marvin, originally from Palo Alto, California, tells us about being a pilot in Alaska. Most of the pilots are either young like him, or over fifty. Those in between might be flying big commercial planes instead, which Marvin says he might do someday. But he’s happy in Alaska. “Most of the places we fly you look out and there’s nothing human to see,” he says as we gaze down at mountains, bogs and rivers. “This is some of the most fun flying you can possibly get paid to do.” And Alaska is one of the few places you can profitably fly a nine-seat plane, he says.

It’s snowing in Fairbanks so as we get closer, our view diminishes until we see nothing but white. Even though Fairbanks only has a population of about 31,500, as soon as we land, I feel the city around me with its buildings, roads, and civilization. It’s hard to imagine me chucking my urban life to move north of the Arctic Circle. But spending a night up there gave me a taste of the huge wilderness and why people dream of inhabiting a little dry cabin in Alaska.![]()

Portland travel writer Teresa Bergen’s most recent contributions to EWNS have profiled digital nomads in Idaho and explained the attractions of cemetery tourism.