After two years of Covid lockdowns, Japanese tourists are returning to Honolulu These two friends pause for a photo at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel on Waikiki Beach. Photo by David DeVoss

By Mark Orwoll

Should you visit America this summer? The past decade has cast a pall over inbound travel to the U.S.A.

German tourist murdered at the California resort town of Idyllwild. Chinese immigrant attacked in New York. British holiday-makers robbed at gunpoint in L.A. What’s next? Random floggings in the public square? Kidnappings in the international arrivals hall at JFK’s Terminal 4?

Such violence against overseas guests, though statistically rare, has led several foreign governments to issue travel advisories against visiting America. In 2019 alone, the Japanese Consulate General in Detroit warned of “potential gunfire incidents everywhere in the United States.” China cautioned its America-bound students that “recently, shootings, robberies and theft have occurred frequently in the U.S.” Even Venezuela’s Foreign Ministry admonished its citizens to postpone trips to the U.S. altogether “due to recent acts of violence.”

Welcome to America!

Now watch your step….

And yet, with few exceptions, foreign arrivals in the United States have continued to climb every year since 2000. Are the rest of us missing something here? It wouldn’t be the first time.

International visitors were the ones who popularized tourism in Harlem, where they enjoyed the jazz and soul food while the rest of America quaked in a gooey puddle of fear at the mere thought of traveling north of Manhattan’s 96th Street. If it weren’t for Italian fashion photographers, Latin American party-goers, and the ever-curious Japanese, Miami Beach might still be the somnolent, run-down pensioner enclave formerly known as God’s Waiting Room.

Oh sure, foreigners still go in for the “tourist attractions,” of which America has an abundance. Overseas visitors should (and do, in huge numbers) go to cliché locations like Times Square, the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and the Las Vegas Strip. But most foreigners who go to the U.S. are looking for something more than flash and dazzle. They want places that are representative of America’s natural wonders, history, and people. In this post-pandemic world, they are in search of meaning and authenticity.

And no, Disney World, you aren’t on the list.

Greed and Greatness on Wall Street

This statue of a large metal bull embodies the strength of the U.S. stock market. When trading is brisk and stocks are increasing in value, the U.S. is said to be enjoying a “bull market.” A “bear market” characterizes a period of falling stock values.

A fundamental tenet of American ambition is that anyone, through sheer dint of effort and uprightness of character, can become wealthy. Korean-born Do Wan Chang, the billionaire founder of Forever 21, worked three jobs when he first came to America. Shahid Khan, one of the world’s richest men, washed dishes for $1.20 an hour when he arrived in the U.S. from Pakistan.

The fact is that the average American, who probably doesn’t like to work any harder than the average Singaporean or Kenyan, can attain wealth through such government-sponsored financial-planning strategies as buying Mega Millions lottery tickets. Or investing on Wall Street. For the sake of argument, let’s focus on Wall Street.

“The Street,” where untold numbers of fortunes have been made and lost, isn’t the top tourist destination in New York City. It may even be lower on the list than the Museum of Sex at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 27th Street. But for anyone who wants to understand America’s fascination with wealth, it’s a worthwhile, historic, and even picturesque stop. Many of the august buildings in its environs were constructed in the 1910s and ’20s, when architects specialized in grace and grandeur, and the men who paid for those early-day skyscrapers were, by the looks of things, desperate to get their money’s worth: opulent marble-lined lobbies, massive columns guarding their entrances, scrollwork and stone ornamentation on the façades of neoclassical, streamline moderne, and art deco skyscrapers. One wonders if Louis XIV, the Sun King, the original Limelight Kid, might have blanched at their show-offy gleam.

Wall Street is where a visitor can see the New York Stock Exchange, arguably the most famous financial institution in the world, in a handsome 1903 neoclassical building. Although visitors haven’t been allowed since the terrorist events of 9/11, the building can be seen and photographed from outside. Around the corner, in Bowling Green, is the famous bronze Bull of Wall Street sculpture by Italian-born Arturo Di Modica, today a symbol of the market, and well known for its shiny (and impressive) balls, hand-rubbed to a radiant dazzle by the excitable palms of hundreds of thousands of tourists since it was, shall we say, erected in 1989.

New York’s Wall Street is the center of the world’s largest economy. Trinity Church is visible through one of the financial district’s “concrete canyons.” A statue of George Washington stands in front of Federal Hall. Now a museum operated by the National Park Service, the building in October 1765 was the site of the Stamp Act Congress in which delegates from nine of the 13 original colonies drafted a message to King George III claiming the same rights as residents of Britain and protesting the Crown’s policy of “taxation without representation.” Photo courtesy of NYC & Co.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, whose name is as sleep-inducing as its importance to the economy is eye-opening, resides splendiferously in a 22-story, block-long, Italian Renaissance-style building (constructed in 1924) full of vaulted ceilings, columns, and other ornamentation, just two streets away from the NYSE. The Fed, as it’s called, is one of 12 federal reserve banks in the U.S. that direct the country’s monetary policy, set interest rates, and regulate the banking industry. But of much more interest to a visitor is the opportunity to tour the Fed’s underground vaults holding millions of dollars in gold bullion. One imagines the Fed president, late at night, rubbing his hands in the vault room, letting loose with a hearty, “Bwa-ha-ha.” For a facility so concerned with money, it’s pleasantly ironic that tour tickets are, yes, free.

Opposite the stock exchange at Wall and Broad streets is Federal Hall, a magnificent neoclassical building constructed as a customs house in 1842 on the site of the nation’s first Capitol. Today, it serves as a museum celebrating the founding of the nation. So impressive is Federal Hall’s exterior that some visitors (and even some locals) mistake it for the stock exchange.

Trinity Church, built in 1846, anchors the western terminus of Wall Street, at Broadway. In the 2004 Disney film National Treasure, Trinity Church features prominently when adventurers find a cache of gold, jewelry, and artifacts buried below. Its predecessor served as a place of worship for many of the country’s founding fathers, including George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, the latter of whom lies buried in the churchyard. Yes, that Hamilton, the all-singing, all-dancing first secretary of the U.S. Treasury.

Into the Valley of Death

When you’re running low on water in the desert the last thing you need is a teakettle. Left by exhausted hikers over the years, this colorful assortment of excess baggage is a vivid reminder of the need to bring plenty of water. Photo courtest of the National Park Service.

As a generalization, Germans are the most off-the-beaten-path travelers on earth. They are fearless and will go to the literal ends of the planet to explore something new.

Take Death Valley, on the eastern edge of Central California and among the hottest places on the planet, whose merciless climate has an almost pheromonic allure to Teutonic tourists. Since 1933, the bare, brutal, arid moonscape has been a national park—which in itself tells you something about American culture. Despite its topographical name, the place is less a valley and more an unforgiving desert full of plains and hills, bleached cow skulls.

Summer temperatures of 120 degrees (49 degrees C.) are common. So are the near-comatose bodies of heat-prostrated hikers who forgot their water canteens back at the trailhead.

The main settlement is aptly called Furnace Creek. Its nearby 18-hole golf course, at 214 feet (65 meters) below sea level, has the lowest putting green on earth and water hazards that are more likely to be shimmering mirages. Not far from there, Badwater Basin sits 282 feet (86 meters) below sea level, the lowest point on land in the Western Hemisphere. In the area called Racetrack Playa, rocks the size of a man’s head glide mysteriously across a hardpan desert floor; the movement of these so-called “sailing stones” is so slow that it can’t be detected by the naked eye, only by the paths the rocks carve through the choking sand en route to the far side of a dead lake.

Ready to visit Vacationland U.S.A. (as Death Valley will never be called)? Well, international visitors are. Big time.

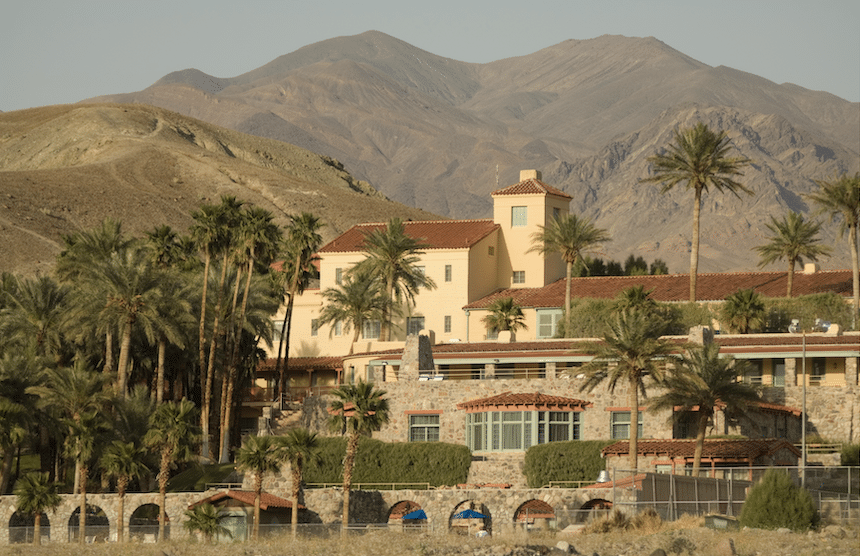

Furnace Creek Inn & Ranch Resort in Death Valley, California. Photo by Robert Holmes for the California Travel & Tourism Commission

Few official statistics exist documenting international versus domestic tourists in Death Valley. But according to one such study published in 1996 by Washington State University, 69 percent of short-term guests are foreigners. Of those, 42 percent were from Germany, followed by the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and 22 other countries. International travelers were far more likely to visit Death Valley than Californians, who made up only 7 percent of visitors, or next-door Nevadans (a wimpy 3 percent)—proving that internationals, once again, often lead the way for Americans to discover their own backyard.

Remember to carry plenty of water.

Hikers entering Gower Gulch in Death Valley walk through dramatic and beautiful desert, but they must respect the terrain. Photo by Finetooth, Wikimedia Commons

The Ethnic Enclaves

It’s counter-intuitive, but there may be no better place to find the soul of America than in its immigrant communities. After all, even Jamestown, Virginia, established in 1607, and Plymouth, Massachusetts, settled in 1620, were once, technically, immigrant communities. They are now omnipresent—not just in the major port cities of the East and West coasts, but even in the unlikeliest of places.

Traditionally, in large American cities you could find a neighborhood called Little Tokyo (Los Angeles), Slovenian Village (Cleveland), Greektown (Chicago), Little Haiti (Miami), Spanish Harlem (Manhattan) or the like. Nowadays, those ethnic enclaves are not the sole domain of the large metropolises, but can also be found in smaller cities, rural towns, and the spreading suburbs. After the Vietnam War, for example, refugees from Southeast Asia flooded into the orderly bedroom community of Westminster, California, and became one of the most influential groups in surrounding Orange County. These days you’ll find Little Seoul in Newport News, Virginia; Little India in Hicksville, New York; Little Mogadishu in Minneapolis; Little Manila in Carson, California; and on and on in such unexpected places.

Go into any medium-sized city in the U.S. and ask for a map. You’ll probably find a neighborhood called Thai Town or Little Bangladesh. In New York’s Borough of Queens, the city of Flushing has one of the most vibrant Chinese communities on the East Coast. Photo by Chad Davis, Wikimedia Comons.

One of the most exciting of those neighborhoods—and, strangely, not particularly well known by those who live in the city at large—is New York’s Chinatown. No, not the one you might be thinking of in Lower Manhattan. The Chinatown that is thriving, booming even, is in the Flushing section of Queens, which also happens to be the most ethnically diverse of all New York City’s boroughs.

Unlike the other (Cantonese-speaking) Chinatown, with its touristy restaurants and stage-dressed streets, the (Mandarin-speaking) Flushing Chinatown is a bustling center of commerce, industry, entrepreneurship, education, and cultural events. Initially populated by Taiwanese immigrants in the 1970s and nicknamed Little Taipei, the area was inundated by Mandarin speakers from mainland China some 25 years ago and earned the moniker Mandarin Town, now better known as Flushing Chinatown. The burgeoning neighborhood has become so renowned throughout Asia that today you will find nearby satellite immigrant islands of Vietnamese, Thais, Cambodians, Laotians, and Indians, along with Asian-owned sari boutiques, second-hand shops, ice cream factories, bookstores, and restaurants galore.

If you visit, come hungry.

Minor League Baseball: A Home Run

Football may be America’s most popular spectator sport, but baseball is where a visitor will find a more revealing aspect of America’s essence. Come and see what a real baseball game is all about. Baseball season begins in early April and there are thirty Major League teams spread across North America. The best introduction to America’s “National Pastime,” however, can be had at a minor league game.

Unlike the athletes in basketball and football, baseball players rarely go directly to the major after graduating college. Most spend one, two, three, or more years in the Minors before getting a shot at the Big Leagues. That means attendees at Minor League games have a good chance of spotting the next Cal Ripken Jr. or Mike Trout before they break into the big time. Minor League games also offer an opportunity to see what good old-fashioned baseball is all about, without the million-dollar salaries, the $125 first-base tickets, and the $12 stadium beers.

A day game at Victory Field, home of the Indianapolis Indians. Photo by O Yonikasz, Wikimedia Commons

The Minor Leagues’ stadium seat capacity is significantly less than in the Majors. Consider that Yankee Stadium in New York holds 54,000 people, and Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles holds 56,000. By contrast, the highest seating capacity of any Triple-A club (the highest level of the Minor Leagues) is 16,600, at Sahlen Field, home of the Buffalo Bisons. The smallest, at just 6,500, is Cheney Stadium, where the Tacoma (Washington) Rainiers play. As a result, your seat is likely to be much closer to the action than at a big-league park.

The ticket prices are another reason to try a Minor League game. The cheapest ticket at Oracle Stadium, where the Major League San Francisco Giants call home, is $40 in the uppermost tier of the outfield, where you’ll need binoculars to watch the action. Compare that to a reserved infield seat directly behind third base with great sight lines at Dell Diamond to watch the Round Rock (Texas) Express play—for just $22

Minor League players are approachable. In fact, they’re so eager to be recognized, and ideally get moved up to the Majors, that they go out of their way to interact with the fans, signing autographs, posing for selfies, and in general being regular human beings, not superstars.

You don’t need to visit the American hinterlands to visit their stadiums, either. You’ll find Minor League games being played in a number of major metro areas, including Las Vegas, Austin, Charlotte, Indianapolis, Jacksonville, Nashville, Reno, Sacramento, Salt Lake City and Cucamonga just outside Los Angeles.

But whether one attends a Minor or Major League game, baseball is a fundamental way to learn what makes Americans tick. Rare is the U.S. sports fan, for example, whose heart doesn’t stir when he enters a stadium and find himself—suddenly, unexpectedly, wonderfully—gazing out over an emerald green baseball field, every blade of grass in place, precisely mown and edged, as if by hand with eyebrow tweezers. The brown basepaths of the infield, made from a chemically balanced blend of sand, silt, and clay, form an eye-pleasing geometric base to the fan-shaped field. Stadium arc lights, incredibly bright but somehow not harsh, carve the entire scene into such clarity that it seems like an illusion.

Until, that is, the players are introduced and the home team trots out onto the field, casually but confidently. The pitcher lobs a few hard pitches to the armored gladiator-catcher behind the plate, who then sends the ball sizzling to the third baseman, who in turn blasts it around the horn to the other infielders.

And the game begins—but not before the grunted cry from the home-plate ump:

“Play ball!”

Perhaps more than any other American sport, baseball is also about food. If you want a snack or a beer from a strolling vendor, catch his eye (stand up if you need to), raise as many fingers as you want items (two fingers for two beers, three fingers for three bags of popcorn), hand your money to your neighbor to be passed down, and then wait for your food and beverage to be passed back to you. It’s a sort of team sport in the stadium seats. Don’t be surprised if the vendor throws your bag of peanuts to you from where he’s standing 15 feet away. Guaranteed, he’ll pitch a strike right into your lap. Sadly, more and more Major League teams are replacing this 150-year-old baseball tradition with, God help us, iPhone ordering apps that accept PayPal. But that, too, tells you something about America.

“Baseball has reflected the good—and much of the bad—of American life, from civil rights to culture to technical advancements,” says Larry Stone, vice president of the Baseball Writers Assn. of America. “But there is tremendous comfort in knowing that it will always be there, in roughly the same form as it was for our parents, grandparents, and generations before that. And for our children as well.”

Order a hot dog with chili and a sprinkling of raw onions.

In Arcadia, Oklahoma, a 120-year-old red round barn, appropriately if unimaginatively called the Arcadia Round Barn, has become a place of pilgrimage for thousands of overseas visitors. In any given year, travelers from more than 80 countries will stop there, inspect the intricate hand-hewn dome, visit the museum full of road-trip memorabilia, ask one of the staffers at the gift shop to sign their guidebook, join in (or just listen to) a Round Barn Rendezvous jam session, and then head off to their next destination. On Route 66.

This gasoline station cum general store alongside Route 66 in Hackberry, Arizona harkens back to the mid 20th Century when the colordul highway was called the “Mother Road.” Photo by Mobilus at Wikimedia Commons.

Precise figures are hard to come by on the numbers of foreigners who traverse historic Route 66 every year, but David Knundson, founder of the National Historic Route 66 Federation, told The Oklahoman up to 60 percent of travelers on the “Mother Road” are from other countries.

For a period during the first half of the previous century, Route 66 was one of the primary arteries across America, from Chicago, Illinois, to the Pacific Ocean at Santa Monica, California. Route 66 was the path followed in the 1930s by failed farmers from Kansas, Oklahoma, and the Texas Panhandle—the so-called Dust Bowl—to what they hoped would be brighter futures on the West Coast. In the 1950s and ’60s, domestic vacationers, in a semi-patriotic quest to “See America First,” would eat Texas steaks and pie à la mode at the highway’s roadside diners, buy authentic Navajo moccasins of dubious origin at Southwestern “Indian” trading posts, check the gas and oil at kooky, eye-catching service stations, and spend the night in neon-lighted tepee motels, lulled to sleep by the soothing roar of Mack semis and caravans of insomniac Hell’s Angels en route to Tucumcari or Barstow. Ah, nostalgia!

“Route 66 offers a true snapshot of just how diverse America really is,” says Jessica Dunham, author of the Route 66 Road Trip Moon guidebook. “I’m speaking geographically, culturally, racially, historically, architecturally, even gastronomically. I can’t think of another single route in the United States that takes you through both our biggest cities and our smallest towns; that shows off our changing landscape from the rolling hills of Missouri to the deserts of New Mexico; and that offers you a glimpse of our country’s history—the good, the bad, and the interesting.”

By the 1970s, great stretches of the road had been destroyed, diverted, or replaced by superhighways. In 1985, Route 66 was officially decommissioned by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, despite an outcry by the cities along the fabled route. Tourism dried up, and many of the roadside attractions went out of business. Not until the 1990s did a revival of interest sweep a certain breed of traveler, including overseas adventurers who wanted to see the “real” America.

Thanks to the strong support of international visitors, a movement is afoot to re-certify Route 66 as an official highway. Many of its aging and abandoned curiosities have been resurrected. The neon signs above the diners and Depression-era motels are crackling and sizzling afresh through the night as they sculpt technicolor-edged shadows along the Mother Road. You may even find a few of the Indian trading posts back in business.

But avoid the “authentic” moccasins. They’re made in Bulgaria.![]()

Former Travel + Leisure editor Mark Orwoll knows his highways. Check out his January 2021 story on historical road trips and a more recent report on how America’s highway network knits together the country’s diverse cultures.