Cyclists on the road from Maum Cross to Cong seldom are troubled by speeding vehicles. Photo by John Poimiroo

By John Poimiroo

Cycling upon the lightly traveled backroads of West Ireland affords time to intimately experience the country, its people and their history.

Until recently, only experienced cyclists even attempted such a ride. Motorists would fly past as brightly colored cyclists peddled laboriously up hills, their bikes burdened with panniers filled with clothes and heavy equipment. Cycling seemed more exhausting than enjoyable.

But with the advent of ebikes and specialized cycling tours, beautiful and fascinating areas now are accessible to nearly anyone. And one of the most bike-friendly places to take such a tour is along the west coast of Ireland.

What makes this type of tour so satisfying is the pace (avg. speed 11 mph) and proximity of being so close to the land and the people you meet along the way.

You can stop whenever you like to appreciate an historic marker, a beautiful garden or scenic overlook when traveling on a bicycle. There’s something about the physical exertion necessary to get from place to place that connects a rider with the land more deeply than if he arrives by bus, train or car.

When you stop, locals will ask where you’re from and where you’re heading. Their eyes widen when they learn you’ve ridden 15 miles since breakfast and will pedal another 10 before stopping for the day. They are awed when you reveal you expect to ride 160 to 400 miles that week. It seems impossible, but it’s not. It’s done regularly by people of average physical ability.

You need not be athletic to enjoy a cycling vacation, but you should build stamina before you go by training on a touring bike. If you ride regularly, just increase your routine, adding a few uphill sections. Need an occasional boost? Then consider a battery-powered ebike. They can be rented in many cities, so familiarize yourself with how they operate before going to Ireland.

A cycling tour is not about seeing a lot of places in a short amount of time. It’s about experiencing a given place intensely and personally, at a casual pace.

In addition to supplying the necessary equipment, tours offered by West Ireland Cycling’s John and Shavon Kennedy handle the logistics of moving luggage from place to place. Photo by John Poimiroo

A half dozen or so cycling tour companies now operate in Ireland. West Ireland Cycling is perhaps the most Irish. Established more than 40 years ago by the great uncle of Galway locals John and Shavon Kennedy, West Ireland Cycling numbers only five employees. It began offering self-guided cycling tours to promote “the culture of Ireland by getting our guests to explore by bike and meet as many people in authentic connections, as possible,” John explains. “We design the tours so they’re not staying in people’s homes, B&Bs and small family-run hotels. We know that if we get riders out into rural Ireland to meet Irish people they will learn something new about Ireland and form real, authentic connections with them.”

Marie Power of Inishmore B&B in Galway is typical of female innkeepers hosting cycling tours. All, like her, have been established for generations and have high standards of service, cleanliness and food preparation. The traditional rooms at Inishmore are remodeled with modern private baths and queen-sized beds. Breakfasts are full Irish classics that features two eggs, two sausages, tomato and white and black sausage pudding. Still hungry? Then grab some smoked salmon, porridge, cereals, fruit, beverages, and lots of Irish brown bread.

Marie Power’s B&B in Galway is known for comfort, cleanliness and huge Irish breakfasts. Photo by John Poimiroo

John Kennedy says 90% of his customers are over 60 years old with up to 70% coming from the U.S. and Canada. They are largely retired and have long dreamed of visiting Ireland. Few are avid cyclists. Most just want to slowly explore. This means the pace is restrained and more about racking up experiences than miles. And West Ireland is jam-packed with experiences.

Each day, riders can choose between three options: a short ride (about 20 miles) a medium ride (40 miles) or a long ride (60 miles). This is done by the tour company shuttling the short ride people to a midpoint or extending the shorter ride. There are uphill sections, but they are few and not generally strenuous.

This is a Gaeltacht region (pronounced gale-tauked), meaning that Gaelic is the region’s first language, though everyone speaks English. As such, it is among Ireland’s most authentic regions where traditional culture and music are alive and plentiful.

West Ireland Cycling’s tours begin in Galway, where cyclists are fitted for their bike (important to ensuring a safe, comfortable ride), meet their co-riders (if joining with others) and have time to adjust to the time change. The tour package includes a nightly room at a local inn, luggage transfers, ferry tickets to the Aran Islands, roadside assistance should you break down (unlikely) and a Trek hybrid touring bike with repair kit and pannier.

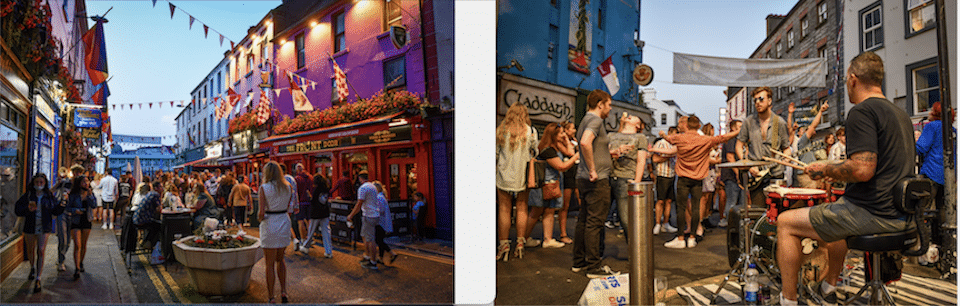

Galway is a medieval university town of 80,000. It is both ancient and modern. Young people on weekend nights pack its narrow streets, listening to musicians while dining alfresco at sidewalk cafes. Many sip pints at noisy pubs as they enjoy lively “Irish trad” while others congregate along the quay to talk quietly.

On a typical summer night, you might see the street crowd letting loose as a rock band plays cover songs across from The Kings Head, a pub that in 1653 was seized by Colonel Peter Stubbers of Oliver Cromwell’s invading forces. Stubbers is believed responsible for beheading England’s King Charles I four years earlier, which explains the name of the pub.

College towns are exceptional places where residents learn about the present as well as the past. Galway may be the liveliest college town in Western Europe. On warm summer nights it vibrates with mirth and music. The hardest thing about a bicycle tour of West Ireland is leaving Galway where the tours begin. Photos by John Poimiroo

Entering the King’s Head is like going back to the Middle Ages. The wood paneling, darkened by time and smoke, has absorbed a thousand years of spirited talk, music and revelry. Galway’s street scene and its many festivals, celebrations and performing arts troupes are why the city is called “Ireland’s Cultural Heart.”

On the first day of cycling, riders are transported by van out to a starting point where they are given their bike and a detailed spiral-bound guide that includes maps, contact information, lodging and guidance on what to do in case of a puncture or emergency. It is secured to the handlebars in a drizzle-resistant, see-through pouch.

At intersections, riders confirm which way to turn. A wrong turn does not prevent a cyclist from getting to the next destination. But it could mean missing a lesser-used narrow path that probably was traveled by foot or horseback in centuries past. Often, these Sean Bòthairs (old roads) lead past abandoned cottages to spectacular views. Capturing the look and feel of history is the point and difference of touring Ireland by bicycle.

Forest trail to Clonbur Photo by John Poimiroo

Ireland is a nation of 4.9 million people. Only half a million live in counties Galway, Mayo and Clare. That means there’s very little traffic on the busiest of the roads you pedal, and virtually none on the backroads and byways.

The first day, from Galway to Cong introduces you to Ireland’s lightly populated, undulating countryside. Rock walls, made of native blue limestone, scribe the green landscape. Some 400,000 kilometers of limestone walls exist in Ireland. They were constructed by farmers, long ago, to mark their pasture and farmland. Some walls were built to give people paid work during the great famine of the 1840s.

“The walls are spaced as far from the center of a plot as a person could carry a rock,” John Kennedy explains. “Elderly women would dig out a stone and brush whatever dirt was attached to it to preserve whatever soil was there. Then the rock would be carried to the wall. Large boulders were placed as a foundation with lighter rocks above. In other places rocks were dry stacked vertically or horizontally with openings between the rocks to allow winds to pass through and not topple the walls.”

Ireland is riven by rock walls like these at Inis Mór on Aran Island. Atop the hill is Dún Aonghasa, a defensive barrier more than 3,000 years old. Photo by John Poimiroo

There were no gates in Ireland’s rock walls. When a farmer needed to move livestock from one enclosure to another, he’d remove a portion of the wall, drive his livestock into the adjacent enclosure and rebuild the wall. This was possible because the walls have no mortar. Many lack even a foundation. Today, farmers have added gates and there is a national conservation effort to keep Ireland from losing its rock walls as they collapse or land is consolidated.

The Irish countryside is not just marked by rock walls and pastures. Every village has a church or pub and all are used for demarcation. Interestingly, pubs outnumber the churches and are often in better locations. Irish maps identify pubs as landmarks and give directions by referencing them. On arrival in Doolin, a local gave these directions, “Ride up the road to Gus O’Connor’s pub, then left and continue past the Fitzpatrick Bar and McGann’s pub. Once you reach McDermott’s pub, your inn is 100 yards ahead on the left. Irish novelist James Joyce wrote in Ulysses, “A good puzzle would be to cross Ireland without ever passing a pub.” So associated is Joyce with pubs that the James Joyce Pub Award is given to Ireland’s best pubs, which “retain a genuineness of atmosphere, friendliness and presence of good company.”

The first day of riding skirts the edges of Lough Coirib (pronounced loch), Ireland’s second largest inland water. Essentially a freshwater sea, it’s so large locals swear it has an island for every day of the year. It’s an inviting expanse of water with nary a boat in sight.

Statue of John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara in Cong, the village where “The Quiet Man,” a 1952 romantic comedy that won an Academy Award, was filmed. Photo by John Poimiroo

If the countryside seems familiar as you descend into Cong, it’s probably because you remember it from the Academy Award-winning romantic comedy, The Quiet Man. The 1952 film was directed by West Ireland descendant John Ford and starred John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. Many of the movie’s locations in Cong remain prominent landmarks. They include a replica of the White O’morn thatched cottage now used as a museum, a bronze statue of Wayne carrying O’Hara in his arms and the ancient church where the film’s characters married. Nearby are the ruins of a 7th-century gothic monastery and 800-year old Ashford Castle, the former vacation home of the Guinness family that lives on as an exclusive luxury hotel.

The route from Cong to Clonbur is a twisting forest trail that crosses a stone bridge beside a 16th-century fishing house that ingenious monks used to net fish from the River Cong. Just beyond the bridge is a lookout tower that Guinness built, but the real attraction is the trail itself. Emerald ferns, blackthorn, elm and oak trees overgrown with ivy grow to the edge of the compacted dirt trail.

The dense forest inspires images of fairies and leprechauns hiding within. It’s easy to imagine why Irish folklore generated so many mythical creatures when you’ve the time to consider what might be hidden as you pedal through a lovely coill (wood).

Sheep graze peacefully next to quiet country roads in West Ireland Photo by John Poimiroo

Time to think is what makes a bike tour different. From Clonbur, there’s plenty of time to reflect as you ride toward Leenaun through a long glacier-carved valley of sheep farms. Occasionally, you’ll see a farmer at a high point along the road using binoculars to locate a ram high on the viridescent slopes of the surrounding hills. Sheep are identified by bold stripes of color sprayed across their backs. Different colors tell farmers whose sheep they’re seeing.

Joe Joyce, a sheepdog breeder and trainer, supplies Irish shepherds with border collies descended from world champion herders. At his farm, Joyce Country Sheepdogs, beside Lough Na Fooey, Joyce runs daily sheepdog demonstrations and regales his visitors with stories as energetic as any Irishman might spin. He uses voice commands and whistles to control his dogs once they’re high on the hillsides. “Come by” means go right. “Keep away,” is go left. “Stand or Lie Down” is stop and “Walk on,” moves the dog toward the sheep. “Without a good dog, we’re not able to manage our flocks,” Joyce says. The idea is to control the dogs from a distance. “I let the dogs do the walkin’ and I do the talkin’.”

As soon as Joyce puts on his leather fedora and picks up his shepherd’s crook, his kennel of a dozen dogs starts barking to be released. They all want to work. They live to work. It is their joy. The tall, gangly handler whistles sharply and the dogs quiet. Then he releases his favorite, a lanky black and white bundle of intensity who has waited patiently for his signal. Off she sprints straight up the mountainside, covering 200 yards in a blink.

Having stealthily crept up behind the unsuspecting black-faced sheep, a dog trained by Joe Joyce is about to herd the flock back down the hill. “Walk on,” doggie. Photo by John Poimiroo

High on the hill, five native Connemara black-faced sheep lift their heads instinctively, aware that something has changed, though they haven’t yet seen the dog. Silently, the dog loops high around and above the sheep, then approaches from behind a flock. Joyce’s commands are spoken softly and encouragingly. The collie responds as if wired to Joyce, moving right, left or stopping as told. “Walk on, come by, walk on, keep away, lie, lie down …” Down the hillside the sheep march begrudgingly, driven by the border collie whose insistent presence is their only reason for moving.

At the Sheep & Wool Centre in Leenaun, Seamus Kirwan describes Connemara’s long history of spinning and weaving. Today, sheep farms throughout the region depend on the export market to sell lamb and mutton. The woolen industry is largely supported through tourism, which drives purchases of spun wool, Irish tweed and sweaters, scarves and blankets. The center sustains Ireland’s traditional economy by connecting travelers with farmers and artisans.

At the Sheep and Wool Center in Leenaun, Seamus Kirwan explains the wool industry’s importance to Connemara’s economy. He’ll also sell you a woolen blanket or sweater if you’re feeling a chill. Photo by John Poimiroo

Says Seamus Kirwan: “During the recession, things were difficult for Liz Christy, a weaver from Castleblayney in County Monaghan. When things got very bad she thought, “Oh, God, I’m going to lose my business.” There were all these scraps falling on the floor and she was sayin’ to herself, “even that’s a waste. What can I do with that?”

“Then she had the idea of making tiny broaches shaped like sheep using the bits of yarn trimmed from her scarves. She started makin’ them, and they started to sell. So, when she wasn’t selling scarves, the little sheep started to sell.

Cycling Through West Ireland Photo by John Poimiroo

“She calls them,” smiles Seamus, pointing to the broaches, ‘The sheep that kept the wolf from the door.’ That’s what helped pay her mortgage ’til things picked up again.”![]()

John Poimiroo is a travel writer/photographer living in California’s Sierra Nevada near Sacramento. He is a member of the local American River Bike Patrol. This is his first story about bicycle touring for the East-West News Service.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]