By Larry Bleiberg

By Larry Bleiberg

Everyone, it seems, has a theory about Peru’s Nazca Lines.

The mysterious markings on the desert floor are a massive astronomical calendar. That’s a popular one.

Or maybe they point to hidden reserves of water, the source of life in the desert.

Then there’s my favorite: a UFO landing site. More than 50 years ago, Danish writer Erich von Daniken popularized that idea with his best-selling book Chariots of the Gods?

Now, strapped into a four-passenger Cessna circling over a figure called the astronaut, I’m not sure what to think. One of its hands points to the sky, another to the ground. His owlish eyes stare into mine.

Look at me, the 1,500-year-old seems to say. Can you solve my mystery?

Every day flights leave from the small Nazca airport, offering an aerial view of the Nazca Lines.

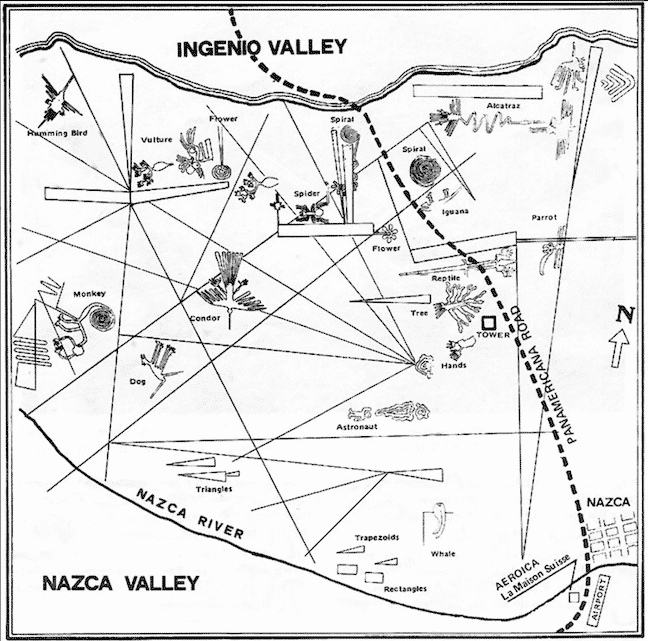

Here’s what’s known: For hundreds of years, the Nazca (also spelled Nasca) people scratched out lines on the ground, creating some of the world’s most famous geoglyphs. Some form familiar figures: a spider, hummingbird and dog. Others–a whale, monkey and parrot—don’t belong in the desert at all.

The only way to properly see the Nazca Lines is from the air. That makes them even more mysterious. How did pre-Inca people make these images without the benefit of flight? And what was the point of forming lines if they couldn’t appreciate their glory? The lines weren’t even discovered until the late 1920s, when a pilot flew over the area and was astonished to see eyes looking up at him.

Thanks to the ancient people, the town of Nazca now has a veritable air force: More than a dozen companies fly planes over the lines. The tours are an industry, as indicated by the handwritten sign taped to my plane’s instrument console. “Tips are welcome,” it says in six languages.

Not bad for a dusty desert town of about 25,000, a seven-hour bus ride south of Lima. The modern city of Nazca, a place that gets less than an inch of rain a year, owes its prosperity to the mysterious markings. Statues inspired by the desert figures decorate the town plaza. Sketches of the lines are everywhere else. Elongated hummingbirds mark store signs, while a lizard graces City Hall. On sidewalks, brass inlays of a monkey and spider reflect the sun.

Artwork inspired by the Lines decorate the dusty desert town of Nazca.

But the lines might have been forgotten without Maria Reiche. She came to Peru from Germany in the 1930s as a tutor and eventually dedicated her life to documenting the creations. For years, she surveyed the area, measuring the markings, clearing away debris and pondering their meaning.

To the local people, she was the gringa loca, a crazy woman sweeping the desert. But the world came around to Reiche’s way of thinking before she died in 1998. Her statue now overlooks the city plaza. UNESCO declared the area a World Heritage Site, but not before some lines were destroyed by development – the Pan American Highway cuts a lizard’s tail in half.

And the threat continues. In 2018, a truck driver made global headlines when he left the highway and drove over the lines, damaging three figures.

Only a few spots allow visitors to get a close look at the lines. A roadside fire tower, built with Reiche’s funds, provides a view of two figures: a tree and a pair of hands. Like the astronaut and monkey, the two hands have only nine fingers total. Another mystery.

But the city is generous with theories. Here’s one explanation offered by a guide: Nazca has nine months of blazing summer heat, thus nine fingers.

An observation tower and what appears to be a bird can be seen from an airplane overflight.

Maybe so. But to understand the lines, I first wanted to see them from ground level. A half-mile from the tower, visitors can get a desert-level view of the creations. I kneel to look straight down a line. I see no monkeys, whales or spiders. Just a long, straight pathway bordered with stones and disappearing into the distance in the dusty desert.

The markings were made by clearing away dark rock, exposing white soil below. Archaeologists have demonstrated that using sophisticated surveying techniques it would have been possible for the Nazcans to create figures working from a small model expanded to a large scale. That’s probably how they were built. But one researcher has shown that the Nazcans also could have built hot-air balloons to supervise the construction from above. We’ll never know. The Nazcan culture disappeared, eventually absorbed by the Incas.

Reiche spent her final years at the Hotel Nazca Lines, where she received free room and board in exchange for nightly lectures, during which she wrestled with questions such as these.

The hotel keeps the tradition alive with a nightly planetarium show. I drop in one evening, browsing in the lobby gift shop before a German couple and I are led outside to a circular wooden building for a presentation in English.

As Peruvian flute music plays, the lights dim and an astronomer reviews the theories behind the lines. Reiche, it’s noted, came to believe the lines were a star calendar, and that gets a thorough examination as lines and stars trace across the planetarium screen.

The hummingbird figure, for example, has a line from its beak that crosses the desert and eventually points to the spot where the sun rises Dec. 21, the South American summer solstice.

But only a third of the lines can be linked to astronomical observations. It might all be coincidence.

From the desert floor, it’s impossible to see the Nazca figures.

Each figure is made from a single line, we’re told. Some believe the Nazcans would visit their drawings for religious ceremonies, following the lines as worshipers elsewhere in the world walk labyrinths in prayer and meditation.

Another theory suggests that the lines point to springs. Water here is a constant worry. Peru’s coastal desert is one of Earth’s harshest environments. Summer temperatures often top 125 degrees.

The word Nazca means “hard place to live,” but its ancient residents found ways to survive. They constructed a system of aqueducts, channeling water from underground springs to their crops. At one point, an aqueduct flows underneath a river channel.

The underground waterways would clog, so the Nazcans built walkways spiraling down as far as 20 feet, making it possible to clear obstructions and keep the water flowing. I follow one path down to the water level, marveling at the engineering and the startling sight of water coursing through a desert.

That same day, I look them in the face at the Chauchilla Cemetery, about 20 miles south of town. The dead rested in peace here until a century ago, when grave robbers desecrated the huge burial ground. The criminals grabbed pottery and textiles, leaving bodies and bones scattered across the desert floor. And that’s where many remain.

The Nazcans placed their mummies in a fetal position. Many had long hair, some still attached to the leathery skin on their skulls. The scene is creepy even at midday, looking like a bad Halloween display. Then I see mummies of children, and I’m reminded that this was once a place of mourning and sadness. Their small bodies remain heartbreaking centuries later.

Now all the bodies and skulls again face east, waiting for the rising sun and rebirth.

One of the more curious symbols is that of a monkey, an animal hardly native to the Nazca desert. Credit By Diego Delso, CC BY-SA.jpg

It’s sobering, but I had come to celebrate the Nazcans’ genius, not their demise. I had come to see their lines from the air.

Nazca’s airport is little more than an open-air waiting room. Visitors line up for the 25-minute flights, which cost less than $100.

I share a plane with a couple from Spain, who take the back seat. I’m the co-pilot. Before takeoff, we’re given a map showing our route and the dozen or so figures we will see.

The pilot introduces himself, then radios the control tower for permission to take off. I’m unnerved when he writes the runway coordinates on his hand. Before I can back out, we’re airborne.

In moments, the city of Nazca gives way to wide-open desert. Lines stretch everywhere. There are literally thousands, covering hundreds of square miles, but only a small percentage form recognizable figures.

Etched into the desert floor, “The Hummingbird” probably is the most recognizable image. By Diego Delso, CC BY-SA.jpg

The pilot taps my shoulder and points. There’s a whale swimming forever through the sand. We circle it twice before moving on to the next figure, like a game of aerial connect-the-dots. Next come a pair of trapezoids – Erich Von Daniken’s UFO landing strips. Then we circle the astronaut, who looks forlorn on the hillside, his big eyes staring up.

We pass a dog and a monkey. That’s when I make my own Nazca Lines connection: The monkey’s spiraling tail looks just like the path leading down to the aqueducts.

As we circle the figures, the plane tilting and dipping, my head starts spinning. I feel the blood drain from my face.

The pilot guarantees his tip when he nudges my shoulder. He pours some alcohol on a cotton swab and hands it to me, motioning for me to hold it to my nose.

The pilot guarantees his tip when he nudges my shoulder. He pours some alcohol on a cotton swab and hands it to me, motioning for me to hold it to my nose.

My head clears.

During the next 10 minutes, we pass a spider, hummingbird, parrot, hands and a tree. I had seen the latter two from the tower the previous day, but now the altitude guarantees a spectacular view.

The pilot circles one last time and heads back toward town.

Back on the ground, I take a shaky step down to the tarmac.

The Nazca Lines remain a mystery to me, but I now have a wish for the ancient people.

If aliens ever did fly in circles over the desert in southern Peru, I hope they tipped their pilot well.

Based in Charlottesville, Virginia, freelance writer Larry Bleiberg is President of the Society of American Travel Writers.