By Peter Greenberg

The hospitality industry is hurting because of the coronavirus, but despite lower occupancy rates a number of new hotels are on the verge of opening. Buit what attracts me isn’t the newest construction but hotel properties with a lot of history. There are historic hotels throughout the world, but the ones below are places where I’ve stayed and always like to return.

Most people have never heard of French Lick, Indiana. It’s a town of 1,800 that some would say is in the middle of nowhere. However, a lot of history can live in small town. In one particular place, French Lick Resort, lies a hotel with a past.

What started out as two separate hotels—the French Lick Springs Hotel and the Baden Hotel—have been combined under one management and restored.

These hotels go back to 1845 when a physician began exploring the healing properties of nearby mineral waters. He created a retreat and after he built it, they came—by the hundreds. Sadly, the mineral springs closed, and these two hotels started to fade until a concerted effort—requiring millions of dollars—commenced a major restoration.

Renovation Architect George Ridgeway was brought in to supervise. “We’ve been at it for almost 20 years,” Ridgeway says. “We’ve spent $560 million on this project already and we’re in it for the long haul.”

The hotels are connected by an authentic diesel trolley built in Portugal in 1930. You might be able to catch a ride on it with Sheryl Yeadon, the Trolley Supervisor. She’ll tell you about local history and take you by such places as the Indiana Railroad Museum, which was built by the Monon Railroad in the late 1800s.

At the top of the hotel is a small room, closed to the public and shrouded in mystery. It’s only 16 feet in diameter, with an aged wooden floor. That’s where you’ll find five faded frescoes painted on the wall, including angels and cherubs. Nobody knows who painted them or when. But one thing is clear: it all happened before 1915 when graffiti covered the painted surface.

The West Baden Springs Hotel’s domed atrium is 200 feet in diameter with a 100-foot ceiling. It was the largest freestanding dome in the world until 1964, when a place called the Astrodome started construction. If you stand in the center and clap your hands, you’ll hear more than one echo. According to George Ridgeway, there are 27 echoes.

On these 3,000 acres in French Lick, the two hotels represent 161 years of architecture, art, space, and stories. Those stories still continue, because folks are finding out new things about these hotels almost every day.

On these 3,000 acres in French Lick, the two hotels represent 161 years of architecture, art, space, and stories. Those stories still continue, because folks are finding out new things about these hotels almost every day.

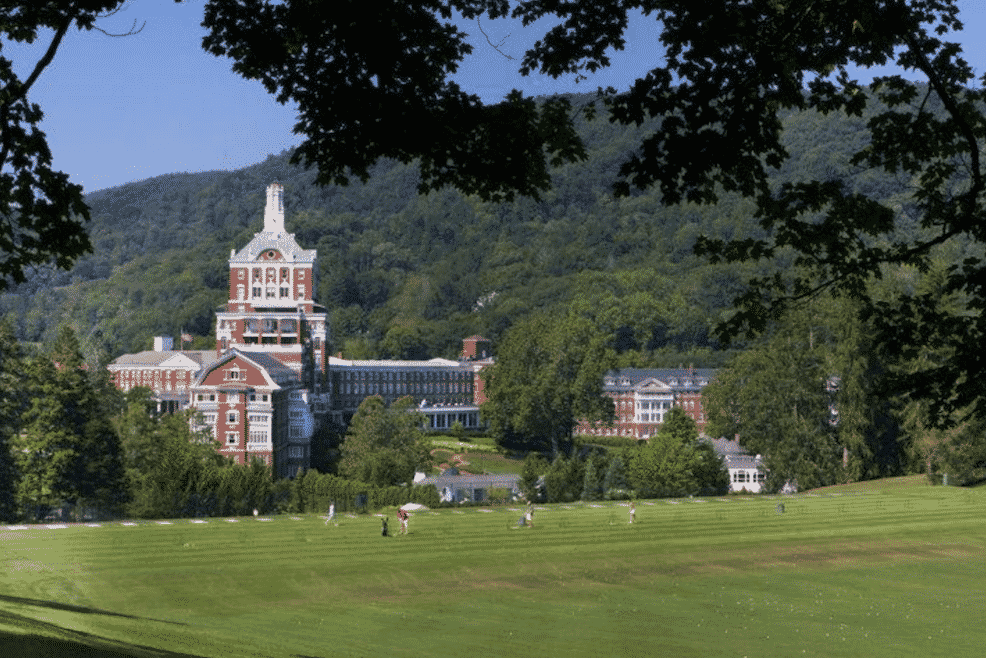

Many people have heard of The Omni Homestead Resort in Virginia, most notably a few U.S. Presidents. While many hotels claim to have a history, this one has actually made history.

The Homestead was the first resort of in the United States. In fact, it started in 1766—10 years before America became a country. It’s on 23,000 acres in the heart of the Allegheny Mountains in Bath County, Virginia, and one of the first members of the Historic Hotels of America.

It began in 1764, after the French and Indian War. Colonel George Washington gave a 300-acre land grant to Captain Thomas Bullitt, who then brought his militia to the hot springs. In 1766, the Homestead hotel was constructed and named for the homesteaders who camped in the area and built the hotel.

In 1818, Thomas Jefferson spent three weeks at the hot springs, bringing the location national recognition.

Julie Langan, director of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, knows all the stories. “These are the oldest and most authentic bath houses in the entire United States,” said Langan. “They continue a tradition of therapeutic bathing that started in Europe and goes all the way back to the Roman times and still operating today.”

“It’s a national treasure,” Langan continued. “But what really, to me, is so special is how authentic it is. This is how it was built, and this is how it’s always been. So, you’re going back in time every time you come here and take these waters.”

“It’s a national treasure,” Langan continued. “But what really, to me, is so special is how authentic it is. This is how it was built, and this is how it’s always been. So, you’re going back in time every time you come here and take these waters.”

But that’s not the only historic activity they’ve kept alive. The Homestead’s Old Course has the oldest continually used golf facility in the United States. The Tee area boasts visits from U.S. Presidents Truman, Taft, Eisenhower, Nixon, and Bush. These days, the course is still in full swing.

In 1901, a fire nearly destroyed the resort. One of the few buildings that remained standing was the casino. It’s not a real casino, but historians will tell you that fortunes have been won and lost here over the years in legendary—supposedly friendly—gentlemen’s card games. Today the building serves as a restaurant.

The Homestead wasted no time renovating and by 1902 it had all been completely rebuilt. The brick ovens dating from 1902 are still in continuous use. If you’re lucky, Executive Chef Greg Barnhill will be making donuts using a recipe that’s been around for more than 120 years. if the donuts date back more than a century, the rest of this historic hotel is well worth visiting.

When you think about iconic hotels, it’s hard to beat The Plaza Hotel in New York.

Built to resemble a French chateau, The Plaza opened in 1907 as a hotel and residence. The construction cost was $12.5 million dollars, which at the time, made it one of the most expensive structures in the city.

“It was designed by Henry Hardenburgh, who was one of the most prominent architects of luxury apartment building at the time,” says George Cozonis, Managing Director of The Plaza Hotel. “His charge was to create the most luxurious hotel in the world. Not only that, but the concept back then was to create a hotel for distinguished visitors, for transient guests, and a structure that had residences for wealthy people who had homes in the country. This was a great benefit since it meant wealthy New Yorkers wouldn’t have to maintain a full house in the city and a full house in the county. So, when The Plaza first opened, it had hotel rooms, transient hotel rooms—and it also had luxury apartments.”

The coincept worked. For over one hundred years, the hotel has been a magnet for the rich and famous.

“The Plaza has been the setting for many special moments involving celebrities, and some have been private moments, and some have been very public moments,” Cozonis explains. “For example, Marilyn Monroe gave her first major press conference at The Plaza where her strap of her dress accidentally and strategically snapped. And it’s still remembered. The Beatles when they first came to America stayed at the Plaza.”

No doubt many iconic performers sang their hearts out in the once legendary plaza nightclub, the Persian Room. In its 41-year run: Bob Hope, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Liza Minelli, Eartha Kitt, Ethel Merman, and Lena Horne. Miles Davis even recorded a live album there in 1958.

The Plaza has changed over the years—but what has remained unchanged is the legacy of exceptional luxury and service.

The Plaza has changed over the years—but what has remained unchanged is the legacy of exceptional luxury and service.

“At the end of the day, we as hoteliers, hotel professionals, are here to make our guests happy. And when you cater to a clientele that is sophisticated, travels a great deal and is used to the best, the standards are exceptionally high,” says Cozonis. “But I think the most important part of luxury is the human touch. It’s the people who deliver an experience which is truly emotional, engages the senses and engages the mind and the soul.”

Several famous authors stayed at The Plaza, such as Truman Capote, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Kay Thompson. Does that last name not ring a bell? Thompson wrote about one of the hotel’s most famous residents, a character I grew up with: Eloise.

Eloise wasn’t just a great children’s book. It was a statement to kids everywhere about fun, freedom, and yes, entitlement. If the Friday afternoon Eloise High Tea is not enough for you, there’s always the Eloise suite. “The Eloise suite is one of the favorite suites we have at the hotel,” Cozonis explains. “It is painted all pink and white and decorated with stripes. Eloise’s clothes are still in the closet. The room is available for girls and their families to rent and it’s one of our most popular suites.”

Other hotels are living history, where the owners are constantly remodeling, updating and not just remembering their past –but building from it.

The story of Breakers in Palm Beach County, Florida starts in 1896, but its enduring appeal is its timelessness–140-acres of oceanfront property, a half a mile of private beach, golf courses, and pools–and a reputation for service that’s been indulging guests for decades.

Originally called the Palm Beach Inn, this was the second hotel founded in Florida by prominent oil tycoon and businessman, Henry Morrison Flagler. But when it opened regulars began asking for the hotel down by the breakers, and that’s how this hotel got its name.

The Breakers was a place to see and be seen–and when the hotel went through extensive remodeling in the 1990s–it recreated a space for people to socialize.

The hotel’s restaurant is an ode to the Gilded Age’s emphasis on gathering in communal areas. During the 1950s and 1960s, The Breakers was an institution and one of the founders of classic cocktail culture. At HMF, you’ll find modern twists on classics that have been served here for years like the “Railcar #91”–its take on the famous cocktail, The Sidecar.

Built in 1896, there was a 1,000-foot pier in front of The Breakers. In 1928, the pier was destroyed by a hurricane. The remains were left to form what is now The Breakers Reef. And since the creation of that reef, almost a century ago, The Breakers has become a capital for watersports.

Some people would argue hotels are not only filled with history but can embody the tradition of a location.

The Buccaneer, one of the Historic Hotels of America, has been a part of St. Croix Island in the Caribbean Sea almost as long as the island has been a part of the United States. St. Croix is only ninety square miles and just 50,000 people live there, but the island is a multicultural melting pot, having hosted diverse residents throughout its time.

That list includes one of America’s Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton. He was born in what was then the British West Indies and moved to the mainland in 1772 when he was just 17.

That list includes one of America’s Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton. He was born in what was then the British West Indies and moved to the mainland in 1772 when he was just 17.

The land has seen six previous owners over the years. The first building on the land, the French Great House, was constructed in 1633 by the Knights of Malta. Later, it was turned into a sugar factory and the sugar mill was erected. At these mills, sugarcane stalks were crushed to extract sugar cane juice. This juice was used to produce sugar, molasses, and of course — rum!

Founded by Malcolm Skeoch in 1750, the Cruzan Rum distillery has been supplying the island with rum for nearly five generations. In fact, the majority of vintage cocktails at The Buccaneer are still made with this rum.

From cattle ranch to sugar mill to hotel, The Buccaneer has developed into one of the most traditional hotels in the United States. In fact, everywhere you look, you’re coming up against history. In fact, the staff there will be happy to show you —they’re archaeologists instead of just hoteliers!

Overseas and in Europe, there’s no shortage of historical hotels to explore.

The Corinthia Hotel in London, England is a new hotel, but the building has quite a history—a long one.

It goes back to the 19th century as a different hotel: The Hotel Metropole. It was the largest in Europe when it opened its doors in 1885 under Queen Victoria. The hotel had 600 rooms and stood seven stories tall. The concept of the super-hotel, already popular in America, was just emerging in Great Britain.

It goes back to the 19th century as a different hotel: The Hotel Metropole. It was the largest in Europe when it opened its doors in 1885 under Queen Victoria. The hotel had 600 rooms and stood seven stories tall. The concept of the super-hotel, already popular in America, was just emerging in Great Britain.

But in 1916, the Metropole’s function took a turn, transitioning into government offices.

Winston Churchill worked in its offices during World War I. He wrote about looking out his window and watching hundreds of Londoners pour onto the streets to celebrate the end of the war while hearing Big Ben chime in the background.

During World War II, the building was once again called upon for duty. The British secret service worked here, monitoring German internment camps and helping troops escape or avoid capture.

There are tunnels and passages under the road that led officials to government offices that are in close proximity. Today, they are all locked up and remain top secret.

There are tunnels and passages under the road that led officials to government offices that are in close proximity. Today, they are all locked up and remain top secret.

So how did it become a hotel? It started with $490 million. That’s how much renovations cost in 2008 when the Corinthia Hotel Group purchased the location and sought to bring the building back to its original function as an upscale hotel. The Corinthia was one of London’s largest reconstruction projects of the last decade.

Some of the original features of the Hotel Metropole, such as the ceiling in the Grand Ballroom, were preserved, but there were challenges in blending state-of-the-art upgrades with the original features of a bygone era.

The Corinthia Hotel London has almost 300 revamped guest rooms, with 47 suites—some with two stories and private elevators, dining rooms, and decks overlooking some of Central London’s iconic landmarks.

The Corinthia Hotel London has almost 300 revamped guest rooms, with 47 suites—some with two stories and private elevators, dining rooms, and decks overlooking some of Central London’s iconic landmarks.

Right in the heart of Budapest, Hungary stands another Corinthia Hotel—a building that spans over 100 years. Despite historical setbacks, it has continued to reinvent itself as one of the city’s finest hotels.

It was originally built as the Grand Royal Hotel back in 1896 to accommodate visitors and impress society’s elite. “The hotel at the time opened with 362 rooms and for a very long time until the late 1930s, was Europe’s largest hotel,” said Tibor Mescal, Senior Deputy Manager at the Corinthia Budapest.

“The facilities were very new and modern at the time,” Mescal elaborates. “The elevators were gas operated and also every room had a telephone line which in that time was very unusual to have.”

The Grand Royal was situated on the biggest piece of real estate on the city’s main artery. “The interest was from all sides to try it—not to mention the luxury—you can find it here in the bars, restaurants, saloon, cafes, which was popular among the politicians, Hungarian writers, composers, and poets,” Mescal said.

The Grand Royal was situated on the biggest piece of real estate on the city’s main artery. “The interest was from all sides to try it—not to mention the luxury—you can find it here in the bars, restaurants, saloon, cafes, which was popular among the politicians, Hungarian writers, composers, and poets,” Mescal said.

The hotel’s glory days didn’t last.

During World War II, it closed when the Gestapo took over the building and used it as office space. “First, these facilities supplied every need for the army headquarters,” Mescal explains. “We had in every single room like I mentioned earlier a telephone line, which were still working and could keep in touch with the rest of the world. Not to mention we had our own generator in the hotel.”

The Grand Royal reopened after World War II but prosperity ended abruptly in 1956 when Hungarians rose up against the Soviet Union. The revolution was doomed from the outset. Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest, badly damaged the hotel and once again Hungary disappeared behind the Iron Curtain not to emerge until 1991 when the berlin wall fell.

The 1960s version of the Grand Royal was thought to be pretty racy for a hotel behind the Iron Curtain. But it still couldn’t survive, then closing doors for a third time.

“The hotel closed on Oct 30, 1991, a very sad day,” Mescal explains. “All the workers, 400 people, gathered and took a big photo to commemorate the closing day. At the time it was necessary because the rooms were badly run-down. At the time, the company who managed the hotel didn’t have enough money to do the necessary refurbishments.”

For its current phase as The Corinthia Hotel Budapest, the new owners renovated the entire hotel, keeping only the French Renaissance facade and the ornate ballroom.

Hollywood put the hotel in the spotlight recently. Some believe the old Grand Royal was inspiration for the Oscar-nominated The Grand Budapest Hotel. Mescal thinks others will be lured by his city’s charms.![]()

Peter Greenberg is the travel correspondent for CBS and the creator of the Royal Tour series on PBS