At the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, 39 diverse tribes are represented in dance, stories and artifacts. Photo by David DeVoss

By Jacqueline Swartz

Riding in a van for several hours from Oklahoma City, I kept hearing that we were still in Choctaw Nation. True enough, the Indian Tribal area in southeastern Oklahoma covers 10,864 square miles, including a state park, timbered hills, woodlands, lakes and misty ponds. It’s an eye-opener, a history lesson, a nature experience. With fishing, hiking, camping, boating and horseback riding, it has become a place for visitors to explore and a drive-to destination for people living in nearby states. Dallas is only a two-hour drive away.

Oklahoma is Indian Country. The US Census Bureau estimates that 523,360 Oklahomans are Native Americans, which is about 13% of the state’s population, the second largest percentage of Native Americans (after Alaska) in the United States. This is mainly because of the forced relocation of tribes in neighboring states. In 1830, then President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, forcibly moving 30 tribes to the area that in 1907 became Oklahoma. (Most of the Choctaw people were from Mississippi.) The journey on foot is commonly referred to as the Trail of Tears. Who knew that later, what was considered barren land spouted oil. This was mainly in Osage territory, and it made the resettled tribes there rich. But the allure of wealth drew murderous outsiders. The story of men marrying wealthy Native women and then killing them is the basis for the book, Killers of the Flower Moon, which was turned into a film by Martin Scorsese.

Exploring Choctaw Tribal Lands

First stop, is the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Eagle Aviary, a 45-minute drive from Oklahoma City. It offers a home to eagles rescued from the wild who have been injured and cannot be rehabilitated and released. There are only a handful of Native American eagle Aviaries in the U.S. This one is a sanctuary that replicates some of the eagles’ wild habitat. Director, Jennifer Randell is passionate about the birds. “We believe the eagles fly so high that they can see the face of the Creator,” she says. The Aviary also tracks healthy eagles. During the Pandemic, notes Randell, the eagles stopped dropping their feathers, a process that normally occurs for six months every year. “The vets said the reason wasn’t Covid, it was sorrow – but now they’re molting like crazy,” she says. The Aviary also provides a source of naturally molted feathers for ceremonial use. It is an honor to receive an eagle feather, Randall explains.

The Citizen Potawatomi Nation Eagle Aviary reveres eagles and offers then a safe place. Photo by David DeVoss

The Choctaw seat of government is in the small town of Durant. The tribe which numbers some 200,000, is flourishing and is one of the first indigenous tribes in the US to build a hospital with its own funding.

“We’re a nation within a nation,” notes Cheyhoma Dugger, Director of Development and Membership at the nearby Choctaw Cultural Center. Indeed, in a landmark case, the Supreme Court declared the eastern Oklahoma tribes to be accountable to their own courts rather than state jurisdictions. (Federal laws still apply). This was later challenged – yet what caught the public’s attention was the ruling that the lands remained “Indian territory,” as they were promised. This is important because over the years land allotments were becoming smaller and smaller.

Cheyhoma Dugger, who comes to the job with an MBA from Northeastern University, emphasizes that the Choctaw Tribe is “promoting the southeastern part of Oklahoma – not just Choctaw casinos, but other businesses. And our focus is on education.”

The state-of-the-art Choctaw Cultural Center, where Dugger works, looks to past traditions for inspiration. There are displays of traditional crafts. A thatched section of the ceiling is meant to evoke a basket. A large exhibit features models of traditional dwellings and includes a play area for children. And many visitors head for the moderately-priced café, which serves specialties like Bison chili. A theatre shows films on the history of the Choctaw Nation. Dioramas display people and nature, and tall corn fields are redolent with scent. But in another room, the décor changes to stark black and white signs displaying legal documents.

Detailed dioramas depict 19th-century Choctaw working in the tall corn fields. Photo by David DeVoss

Beavers Bend State Park

Leaving the Cultural Center, the verdant Choctaw lands seem endless. Beavers Bend State Park, like the rest of the Choctaw land, draws visitors seeking unspoiled nature. Inside the park, Beavers Bend Lodge is surrounded by trees and hiking trails as far as the eye can see. Each one of the 40 rooms has a view of Broken Bow Lake. Visitors can rent canoes and paddle boards. Or go on a two-hour cruise with Tiki Tours.

The mist across Broken Bow Lake in Beavers Bend State Park. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

Museum of the Red River

Located in the small town of Idabel, the Museum of the Red River is a spacious, modern museum with permanent and temporary exhibits of indigenous arts and crafts from around the world. It’s free and supported mainly by donors. Occupying pride of place in the spacious lobby is a large dinosaur skeleton. Discovered only 14 miles from the museum, the Acrocanthosaurus atokensis is the largest predatory dinosaur in North America, assumed to be 100 million years old. “What was found was the most complete dinosaur of this species ever discovered,” says director Henry Moy, proudly pointing to the giant’s 67 teeth. A great attraction for groups of children, it is, not surprisingly, the state dinosaur of Oklahoma.

Reba’s Place

A recent southeast Oklahoma success story is Reba’s Place, named for its co-owner, country singer, Reba McEntire. It opened in January 2023 in Atoka, formerly a thriving town, with a main street and red brick buildings. But when several large manufacturers closed, unemployment left the main street with shuttered shops and buildings with ‘for sale’ signs.

Diners flock to Reba’s Place in Atoka. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz.

Enter the Oklahoma native and country singer superstar. Teaming up 50/50 with Choctaw partners, Reba McEntire turned what was once a Masonic Temple into a restaurant, music venue, boutique and event space. Tourists are drawn to the town, and previously boarded-up stores have opened. I saw a vintage store with Gucci shoes in the window. Atoka is becoming a destination, and there are plans for new hotels.

“It has been amazing, a whirlwind,” says Garett Smith, Reba’s niece, who manages the place. “People are coming from as far away as Ireland and Germany, says Smith. She has long been close to her aunt and even lived with her for a time. “When I was seven, I was playing controls in her recording studio. She took me to HeeHaw in Nashville, set me on the hay bale and I started crying,” Smith recalls. When McEntire sang at the 2024 Superbowl, it marked 50 years of her career.

At Reba’s Place, the food is traditional Southern, interpreted by executive chef, Kurtess Mortenson. There are red beans and rice from New Orleans, meatloaf, chicken fried steak, and cornbread. But with a twist. Fried catfish is cornmeal breaded, and comes with sweet corn hushpuppies, fresh-cut French fries, tartar sauce and chow chow remoulade. Among the over-the-top desserts, is homemade banana bread baked in vanilla bean custard and topped with whipped banana pudding, butter crunch pecans and Chantilly cream, served with bourbon butter and maple syrup. As the menu notes, you can’t get too country.

The drinks, too, can be creatively over-the-top, thanks to champion Mixologist, Laura Johnson, who won an award when she was working at Cesar’s Palace in Las Vegas. The Bloody Mary arrives looking like a vertical salad, with celery stalks, cucumber, dill pickle, pickled okra, green beans, pickled pearl onion, lemon and lime.

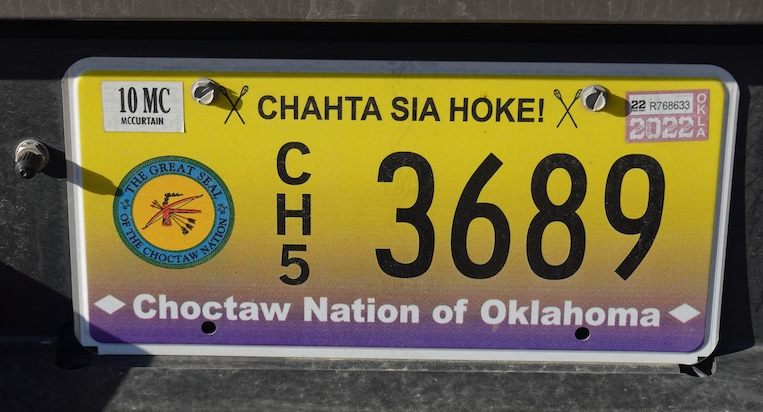

In Oklahoma, citizens of Indian nations can display their tribal license plates if they wish. Photo by David DeVoss

The Native presence is a big part of Reba’s Place. First, the partnership with the Choctaw Tribe. “It’s great to partner with such a force, so well respected,” says Smith. Half the employees working there are tribal members, she adds. But for her, that’s not surprising. “Some of my best friends, kids I grew up with are tribal members,” she says, explaining that her husband’s ancestors are Cherokee from North Carolina. “His great great great grandmother signed the Dawes Rolls, so he has his Cherokee card, as do my kids.” This, she explains, entitles them to benefits including health care, scholarships, grants.

An Asian elephant gets her toenails filed at the Endangered Ark. Experts say the intelligent pachyderms do this in the wild by scraping against objects. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

The Dawes Rolls applies to what the US Government called the five civilized tribes – the Cherokee, Muskoka Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole – accepted by the Dawes Commission. In 1885, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs asked for a census to be submitted annually. Applicants were required to provide proof of descent from a person listed on the rolls from 1888 to 1914. Those who can provide it (along with identification, including a birth certificate) receive a Certificate Degree of Indian Blood or CDIB. Choctaw descendants are required to show proof of only one relative. The US Census Bureau estimates that 523,360 Oklahomans are Native American, which is about 15% of the state’s population.

My trip started with an eagle and ended with an elephant. The Endangered Ark Foundation houses retired circus animals. Visitors pay jumbo prices to see them in the barn, feed them celery hearts, and ride a golf cart to view them in a nearby pond. There are few males, but some offspring have been born. Just one more surprise in southeastern Oklahoma. ![]()

Jacqueline Swartz is a longtime contributor to EWNS. Her subjects range from Romania, France and Germany to India, Africa and the arts.