City Market in Savannah, Georgia. A Place to shop, browse, dine and relax. Photo courtesy of Explore Georgia

By James Cruikshank

Mathematician Edward Lorenz coined the phrase ‘the butterfly effect’ in 1972. He used the term to describe the unforeseen results that stem from seemingly inconsequential changes in the natural order. It’s as if, he mused, a powerful tornado could be started by the distant flitting of a butterfly’s wings.

The historic Georgia coast, a charming amalgam of colonial history and maritime beauty, has played the role of that butterfly many times.

Inscribed into the Spanish moss of Georgia’s barrier islands and ocean townships are some of the most pivotal events in American history. Small flutters in the progress of the region have led to unanticipated roles in the wars, wealth and innovation that have defined America’s character.

Deeper knowledge of the connections of Georgia’s history with the American story provides a better understanding of the people now living along the golden beaches and marshes of the coastal area.

From colonialism to war, to Forrest Gump

A statue of Georgia founder James Oglethorpe in Savannah’s Chippewa Square. Photo courtesy of Visit Savannah & Casey Jones

In 1733, General James Oglethorpe together with 120 migrants aboard the Anne landed near what is today Savannah, Georgia. Oglethorpe was a tenacious supporter of the Enlightenment in the New World, as evidenced in his original founding policies for the state of Georgia. From the state’s founding in 1733 until its overturning by the state’s trustees in 1754, slavery was outlawed. Oglethorpe initially granted land concessions on the islands to the Timucua Native Americans, too.

To coincide with his personal philosophies, Oglethorpe designed the urban space for his port city, Savannah, to reflect the Enlightenment. The Oglethorpe Plan prioritized open commerce and democratic public forums. His urban design put Savannah’s downtown on a rigid grid system with a public park every four blocks, a design that emphasizes walkability and greenspace.

Today, Savannah’s colorful cityscape is a magnet for beach-seeking travelers. From its boutique shops on Bull Street to its back-alley bistros and hidden gems, the city remains a sleepy metropolis confident with its character and traditions.

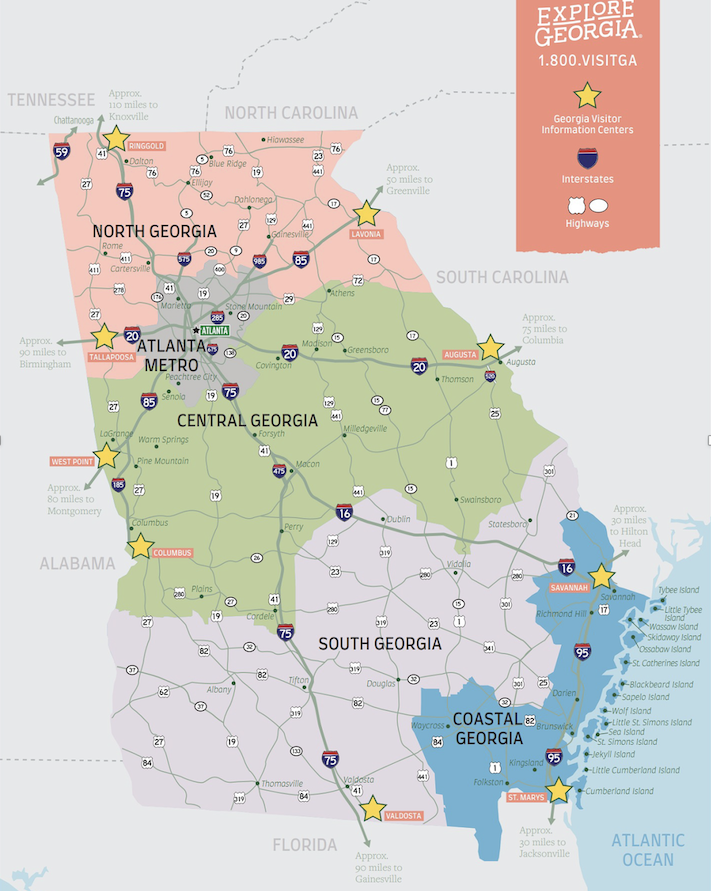

Map of Georgia’s different regions with the coastal region highlighted in blue. Photo courtesy of Explore Georgia

Indeed, Savannah’s downtown boasts a Walk Score of 90, a score higher than New York, San Francisco and Boston. The organization of the flaneur’s paradise could not exist in today’s America – zoning regulations have prohibited the development of walking focused cities for years now. However, it was an unanticipated decision from Union General William T. Sherman that preserved Savannah’s urban structure and beauty.

Marching Through Georgia

In 1864, General Sherman led 62,000 Union troops along the path of today’s Interstate 16 in his infamous March to the Sea. The campaign remains the first and only utilization of total warfare on American soil. Sherman and his men systematically destroyed Georgia’s infrastructure, burning towns and killing civilians while emancipating slaves in their path.

On December 21st, Sherman’s army entered Savannah. The town expected complete decimation. Instead, Sherman enacted a cease-fire. Savannah Mayor R.D. Arnold offered to surrender the city to the Union general in exchange for peace. Contrary to his previous behavior, which today would make him subject to the Hague Tribunal, Sherman accepted the deal. The city was captured with no casualties or destruction.

Savannah remains an antique metropolis due to Oglethorpe’s ingenuity and Sherman’s idiosyncrasies. The centuries-old parks still are frequented by flaneurs, a characteristic that inspired the creation of one of film’s greatest opening scenes.

In Tom Hanks’s Forrest Gump, Forrest sits on a bench in Savannah’s iconic Chippewa Square when he muses that “Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re gonna get.” Behind him, a bronze-cast statue of James Oglethorpe backdrops the conversation.

From Hog Hammock, to Detroit, to golf

Fifty-eight miles south of Savannah is Sapelo Island, a sanctuary of coastal culture only accessible by ferry.

For most of its history, Sapelo was owned and operated by Thomas Spalding, a politician and farmer famous for being “Georgia’s Benjamin Franklin.” In addition to cultivating sugar and Sea Island cotton using experimental methods, Spalding built Sapelo’s historic lighthouse and popularized the shell-laden tabby building material used throughout the coastal region today.

Spalding enslaved 400 people on his plantation, a majority of whom were West African Gullah people who spoke the Geechee creole. Following the Civil War, Spalding, like many of his plantation peers, ceased operations on Sapelo. As a result, his freed slaves organized independent communities on the island, such as Hog Hammock, Raccoon Bluff and Belle Marsh.

A member of Sapelo Island’s Gullah-Geechee community weaves a basket made of sweetgrass. Photo courtesy of Ben Galland

For the following 50 years, the Gullah descendants of Sapelo lived relatively undisturbed. That was until 1911, when Howard Coffin, co-founder and chief engineer of Hudson Motor Company, visited Savannah to spectate an automobile race featuring his vehicles.

Considered the “father of standardization” in mass production, Coffin improved assembly line techniques pioneered by Henry Ford. By thirty, Coffin’s ingenuity made him a multi-millionaire and soon-to-be-married man. As he prepared to slow down his automobile affiliations in Detroit, Coffin looked for a place to call home.

While in Savannah, he was notified that Sapelo Island was for sale. He visited the island and became enamored. In 1912, he purchased the island for $120,000, where he began construction of his opulent mansion and estate. After moving, he coexisted with the Gullah for 20 years.

Coffin’s political clout garnered from his contributions to aviation efforts in World War I ensured that his new home on Sapelo was frequented by the celebrity elite of the nation; presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover as well as Charles Lindbergh were all guests at his Sapelo home.

Realizing his knack for hospitality and love for the salty Georgia marshes, Coffin decided to engage with a new enterprise later in life – tourism. He purchased plots of land to the southerly St. Simons Island and Sea Island in 1926. By 1928, the doors of Sea Island’s Cloister Hotel opened to the public alongside an adjacent golf course and yacht club on St. Simons.

Plantation Golf Course. Photo courtesy of Sea Island Resort & Golf Course

Today, the sister islands of St. Simons and Sea Island are the last refuges of the pervasive wealth and tourist pedigree that define the region. Sea Island, home to the eponymous 5-star resort and hotel, is among the most celebrated and exclusive clubhouses in the state, just behind Augusta National and its neighbor, the hidden Ocean Forest Golf Club.

St. Simons is a charming beach village that remains the quintessential spring break destination for Atlanta natives. A sports-minded community obsessed with world-class golfing, the island boasts several of the nation’s most famous ocean golf courses and is home to many PGA Tour golfers. It’s also an outpost for the University of Georgia Bulldogs football team. It is no secret to locals that legendary coach, Vince Dooley, frequents the island.

Back on Sapelo, Hog Hammock is the island’s only surviving community of Gullah Geechee people with a population of less than 100. In 2001, Cornelia Walker Bailey and Christena Bledsoe published an ethnographic novel about Gullah Geechee life on Sapelo titled God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man.

From Revolution to the Federal Reserve, to Telephones

Christophe DuBignon served as a privateer captain in the French navy throughout the mid-1700s. He seized numerous British ships during the American Revolution while engaging in successful maritime trade. By the 1780s, his business success had transformed DuBignon into a wealthy aristocrat.

Unfortunately, DuBignon achieved wealth at an unlucky time. By the end of the 1780s, revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre had turned the people of France against the aristocracy. In July of 1789, Parisians stormed the Bastille, beginning the French Revolution and placing people of fortune like DuBignon in danger.

Fleeing the specter of the guillotine, DuBignon headed for Georgia where in 1794 he purchased the home of Revolutionary War Major William Horton on Jekyll Island. By 1800, DuBignon owned all the island.

Jekyll Island is part of the Golden Isles, a region of the Georgia coast also comprising St. Simons Island, Sea Island and mainland Brunswick. Though Jekyll is owned entirely by the state of Georgia today, the island was maintained by the DuBignon family until 1886.

In 1886, the Jekyll Island Club Corporation purchased the island which soon attracted the attention of the nation’s elite. Wealthy businessmen began building lavish winter homes on the island to escape frigid northern cities. By 1904, Munsey Magazine claimed it was “the richest, the most exclusive, the most inaccessible” club in the world.

To contribute to the magazine’s claim, the club’s membership included a majority of the most powerful men of the Gilded Age, such as banker J.P. Morgan, news publisher Joseph Pulitzer, railroad magnate William Vanderbilt I, entrepreneur Marshall Field and oil titan William Rockefeller.

Sapelo Island Lighthouse. Photo by Ben Galland

Surely, an innumerable amount of unknown butterfly effects could have stemmed from the fraternizing of the nation’s most powerful men on Jekyll. Few of the backroom deals were recorded. What is known of the club are two remarkable events from Jekyll Island’s heyday.

In 1907, the first worldwide financial crisis of the 20th century destroyed the people’s remaining trust in the banking system. Financial leaders lost faith in the country’s economy, as shaky practices caused stock market panics to occur, on average, once every fifteen years.

In response to the wave of crises, a group of men traveled to the Jekyll Island Club in November of 1910 under sworn secrecy. Known as the ‘First Name Club,’ the group was an all-star team of political and financial leaders that included Rhode Island Senator Nelson Aldrich and Assistant Treasury Secretary A. Piatt Andrew along with prominent bankers Benjamin Strong, Henry Davison, Frank Vanderlip and Paul Warburg.

We’re Just Friends. Nothing to See Here

Driftwood Beach on Jekyll Island at Sunrise. Photo by Explore Georgia

The name of the group was a nod to their first name only policy while in transit, which they practiced to ensure strict anonymity. Public knowledge of the meeting could further damage the banks’ reputations, and they wanted to be irreproachable if any future bills were submitted to Congress.

What resulted from the First Name Club’s week-long gathering to Jekyll was a detailed plan for a central banking entity with 15 branches nationwide that would perpetually safeguard the nation’s economy.

The plan drafted by the First Name Club on Jekyll would go on to be presented at the National Monetary Convention in 1911. By 1913, that same plan would be passed in Congress, acting as the basis for the establishment of the United States Federal Reserve.

The Jekyll Island Club was a site of great innovation, too. On January 25, 1915, AT&T president Theodore N. Vail spoke from the club’s lobby across 4,750 miles of copper wire in the first transcontinental phone call. Vail, while joined by other notable club members, shared a conference call with President Woodrow Wilson in DC, Alexander Graham Bell in New York, IBM chairman Thomas Watson in San Francisco and banker Henry Higginson in Boston.

The opulent club is still in operation today as a hotel and resort. The monumental cottages that used to house the nation’s elite still stand as they did a century ago and can be toured by visitors to the grounds.

From sea turtles to lemurs

Wild horses graze the lawn of the Dungeness Mansion ruins on Cumberland Island. Built by Georgia founder James Oglethorpe in 1736, the residence and 11,000 surrounding acres passed into the hands of American Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Green. His wife built a four-story tabby mansion that was occupoied by the British during the War of 1812. In 1818 Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and the father of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee stayed in the house until hsi death. After the war, the home was razed because of its tangential association with the Confederacy. In the 1880s the property was purchased by Thomas Carnegie, brother of philanthropist and steel industry magnate Andrew Carnegie, who built a 59-room Queen Ann style mansion whose ruins we see today. Photo courtesy of Explore Georgia

These days, the Georgia coast no longer exudes opulence and power. The slowdown follows the flight of the region’s exorbitant wealth paralleled by legislation in Georgia that has safeguarded many of the islands from industrial development.

Since the 1970s, the coast has become a haven of marine conservation. Marine biology students at the University of Georgia frequent the University of Georgia Marine Institute on Sapelo Island. The institute is the premier research center of Georgia’s coastal ecology. Visitors to the center can learn about the flora and fauna of the region, from the importance of marsh grass in oxygen production to the effects of hurricanes on barrier islands.

On Jekyll Island, the Georgia Sea Turtle Center is a museum and hospital dedicated to rehabilitating and maintaining the coastal sea turtle population. On any given day, the center has several sea turtles being nursed to health that visitors can see while they learn about one of the ocean’s rarest species.

The southernmost barrier island in the state, Cumberland Island, has been a designated national park and national seashore since 1972. After being sold to the state by the Vanderbilt family, the island has remained completely untouched.

The island is famous for its wild horses. The Cumberland Island Horse breed is the only feral horse population of its kind on the Atlantic coast. Originally, Spanish missionaries that once lived on the island had a herd of domesticated horses; after the Spanish left, the horses were free to populate and acclimate to the island’s environment.

Some islands, such as St. Catherine’s, are not as accessible to the public for the sake of wildlife preservation. St. Catherine’s Island once was a wildlife haven for endangered species from around the world. Before the early 2000s, researchers would transport critical species to the island to repopulate before returning them to their natural habitat.

Ring-tailed lemurs on St. Catherine’s Island. Photo courtesy of Explore Georgia & Geoff L. Johnson

Today, a population of critically endangered ring-tailed lemurs has a home on the island. The species only lives naturally in the forests of Madagascar. But due to steady degradation of Madagascar’s jungle tree cover, lemurs now struggle to survive there.

According to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, efforts to preserve endangered species populations on the island have ended. Why? Because environmental degradation and poaching make it unsafe for animals who found safety on St. Catherine’s to return to their native habitats.

St. Catherine’s conservation efforts remain essential to the well-being of the Atlantic seaboard. Researchers maintain active bird population counts, do archeological work, conduct frequent hydrology surveys and continue to care for resident sea turtles and lemurs.

Tourism in the Lowcountry

Georgia’s coast does not get as much exposure to travelers from around the country in comparison to other beach destinations. Only 29.6 million travelers stayed overnight on the Georgia coast in 2022 and of that number less than 4 million traveled to the Golden Islands.

Still largely undiscovered, the Georgia coast is a worthwhile destination for travelers seeking epic beaches, stunning coastal environments and monuments and mansions dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. All have a story to tell.

James Cruikshank Jr. is a Duke University student from St. Simons Island, Georgia. He has written previously for The Brunswick News, The Duke University Chronicle, and FORM Magazine.