H’hen Niê, right, joins a dance-company leader in opening the 2023 coffee festival. An ethnic Ede, the beauty queen grew up in a family of coffee farmers in a village near Buôn Ma Thuột. Photo courtesy Buôn Ma ThuộtCoffee Festival.

By John Gottberg Anderson

The people of Vietnam love their coffee, and they indulge enthusiastically in the celebrated beverage. A coffee culture effuses every corner of the country, from the Mekong Delta lowlands to the mountainous Chinese border and all points between. There may be no urban block in Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) without a coffee shop, and sometimes there are as many as a half-dozen on each side of the street.

Credit the French. Although the Vietnamese may harbor little love for the French or their colonial history in Southeast Asia, the modern Viet culture embraces Gallic style, from wardrobe and architecture to — especially — cuisine. Báhn mì sandwiches, crispy baguettes wrapped around pâté and vegetables, are a legacy of the French. So, too, is phở, the rich beef noodle soup that has become an international icon of Vietnamese taste. Bakeries do a brisk business in buttery pastries. The nation has even spawned a wine industry in the mile-high town of Dalat, its grapes first planted by the French when they founded the hill station to escape the oppressive heat of Saigon.

And, of course, there’s coffee. This isn’t the watery blend to which North American and British palates have largely become accustomed, but a stronger brew more akin to Turkish coffee — or a proper French or Italian espresso.

“Here, the way coffee is served, it’s super bitter,” notes connoisseur Christiaan (Kalfie) Bredenkamp, a South African who has lived in Vietnam’s Central Highlands since 2019. “It has a burnt flavor, a little more smoky than a normal coffee. They really roast it heavily.”

Bredenkamp failed to mention that it has a higher caffeine content: A single cup may be sufficient to kick-start the day.

A passion for coffee

Average citizens, especially students and women, but also men between work shifts, gather in cafés instead of neighborhood brasseries. Most shops are tiny, just big enough for patrons to enjoy conversation while waiting for the grind to filter through a four-part aluminum phin, often into a pool of sweetened, condensed milk to balance the bitter essence. More often than not, the brew is consumed iced in a glass: cà phê sữa đá (literally “coffee milk ice”).

Enthusiasts can even find such unlikely adaptations as egg coffee (with beaten egg yolks, sugar and condensed milk) and cheese coffee (a creamy foam topping may be stirred into the drink or scooped out to eat by itself).

Saigon office workers engage in rapt conversation at the Running Bean café in the heart of Ho Chi Minh City’s District 1. On many city blocks, there may be six or more coffee shops on each side of the street. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Đô Phan Trong Tín, 32, manager of a coffee retail outlet at the heart of Ho Chi Minh City’s bustling Ben Thanh public market, says Vietnam has literally hundreds of varieties of coffee. “Every place has its specialty,” he smiles.

“People pay depending upon the freshness of the beans, how they are roasted and blended,” Đô explains. “Every day I ask my customers, how they drink their coffee. Strong or medium-strong? Black or with milk? And how about the aroma? Smoke? Grass? Chocolate? Hazelnut? Coconut?

“Personally, I like a strong aroma of fruit, such as cherry or blueberry. The aroma is already in the bean, depending on the location and the quality of soil where it is grown. I take green beans and do the roasting myself, outside the city. Then I let the coffee rest for seven to 10 days before I sell it,” Đô says.

World leader

Vietnam is now the world’s second-leading producer and exporter of coffee, after Brazil. In fact, Vietnam produces more coffee (17.1% of the world market) than the rest of Asia combined, including Indonesia (7.1%) and India (3.4%). No other Asian country comes close. (Laos and Thailand both stand at 0.4%.)

The berry was introduced to Vietnam by French missionaries in 1857. During the First World War era, it made its way to Dak Lak province and the Central Highlands, where it succeeded beyond farmers’ wildest dreams. Today, about 1.5 million acres in Vietnam are cloaked in coffee shrubs. Most production goes to Europe, Russia and Japan, an annual value of about US$3 billion.

The two main types of coffee in the world are Arabica and Robusta. North Americans and northern Europeans tend to prefer the former, as Arabica is considered to have a smoother, sweeter taste, often with notes of chocolate or berries. But in Vietnam, Robusta accounts for about 97% of production. And in Dak Lak, which produces about one-third of that total (1.8 million tons a year), the coffee is of particularly high quality.

Free tastings and demonstrations of beans of different styles and ripeness were popular features of the coffee festival’s street festival. Photo by Hà Thi Kim Lan

The ancient volcanic soil of the Central Highlands makes it fertile ground. With an altitude between 2,600 to 3,300 feet, Dak Lak is ideal for Robusta production. Lam Dong province, with its hub at Dalat, is less humid and higher, 4,600 to 5,250 feet, so it is better suited to Arabica.

The French brought coffee to Dak Lak farms in the 1920s. Production was disrupted during the Vietnam War — not by napalm, as this crossroads region suffered no major attacks, but by depopulation and collectivization of farms following communism’s victory in 1975. The industry surged again after economic reforms in 1986 reestablished private enterprise.

Coffee Capital

Dak Lak’s provincial capital of Buon Ma Thuot, a Tucson-sized city better known for its elephants and elegant waterfalls, has become home to the World Coffee Museum and the most significant coffee festival in Southeast Asia. Visibly affluent, modern and rapidly growing, “BMT” has at its heart a Victory Monument that commemorates the Viet Cong takeover in 1975. Nearby is a fine ethnographic museum and a summer home of Bảo Đại, the last emperor of Vietnam. Besides coffee, rubber is a lucrative part of the economy, and its straight, slender trunks are widely seen. So, too, are trees laden with cashews and vines of black pepper.

The Buon Ma Thuot Coffee Festival is celebrated every other year, although, like the rest of the world, it took a Covid break in 2021. When the festival sprang back to life in March of this year, it drew many thousands of onlookers from across the country, cheering family and friends in farming and blending contests, joining tours to farms and production facilities. Dozens of producers offered free coffee, merchandise, and samples of beans and coffee-related foods at a busy street fair. More than 50 artists from five Highlands provinces brought their skills and imagination to a crafts competition, where they exhibited works of fine art, both decorative and utilitarian, carved from the trunks of coffee shrubs.

The King of Coffee

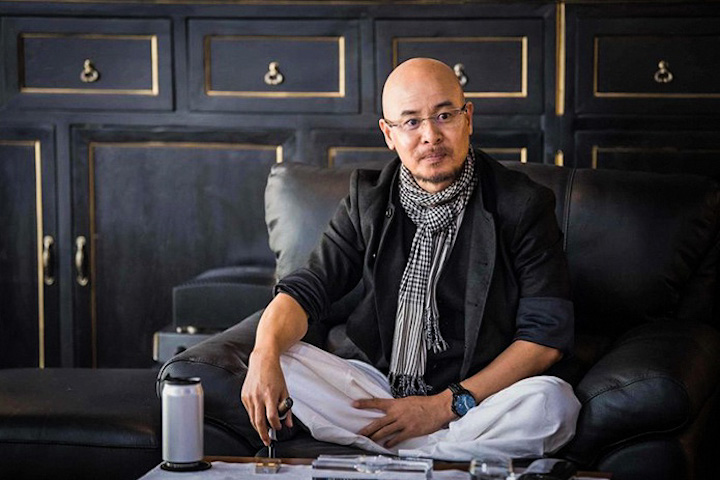

The festival’s commercial focus was on the global market for Vietnamese coffee. Đang Lê Nguyên Vũ, 52, founder and chairman of the Trung Nguyen Legend Group, was the keynote speaker; he announced a goal of building Buon Ma Thuot into the world capital of coffee. Already, Trung Nguyên (the name translates to “Central Highlands”) is the largest domestic coffee brand within Vietnam, exporting its products to more than 60 countries.

Đang Lê Nguyên Vũ, founder and chairman of Vietnam’s largest coffee company, Trung Nguyên Legend, sits in his library at the World Coffee Museum in Buon Ma Thuot. Photo courtesy of Trung Nguyên Legend Group.

Đang opened the World Coffee Museum in late 2018, a little more than a mile from the Victory Monument at the heart of Buon Ma Thuot city. The museum stands atop a grassy mound, its architecture resembling a side-by-side series of nha dai, or long houses, typical of the region’s prominent Ede ethnic group.

Its “History of Coffee Around the World” exhibition presents the stylings of Ottoman, Roman and Vietnamese civilizations. On rotating days, a barista prepares Turkish brew boiled in a tabletop tray of hot sand; Romanesque espresso beverages such as cappuccinos; Thiền (Zen) coffee made using tiny burlap sacks as filters. “The Soul of Coffee” exhibit explores what is required to nurture a coffee tree — soil, water and sunlight — along with the human element that goes into planting, tending, harvesting, processing and preserving the fruit.

On the Farm

Coffee farms are legion throughout Dak Lak. At one 25-acre coffee farm near Buon Ma Thuot, not far from the Sêrêpôk River, spire-like pepper trees, their vines trailing tiny green corns, rise amidst the dense grove. They turn a casual ramble into an obstacle-impeded adventure.

The volcanic soil in the Central Highlands province of Dak Lak produces robusta coffee beans that are pruned on the vine. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

The shrub-like coffee tree — trimmed to about six feet to facilitate the harvest — takes about four years to begin producing its white flowers, and another season before its fruit (“cherries”) emerge, changing in color from green to red as they ripen. The harvest typically takes place in September and October. The “cherries,” picked by hand, are sorted, cleaned and laid to dry upon mats extended across decks or patios. It may take a month before they are ready for hulling. Then the green seeds, or beans, are sorted by size, density and color, and prepared for export.

Depending upon the year, the bean and the region, harvest may begin as early as August, but November and December are the prime months for Robusta. Seasonal workers, many of whom have their own (not coffee) farms, migrate from other provinces for the wages coffee pays.

Beans must be roasted before they are ground into the fine powder that is steeped in hot water and filtered into a cup, making what is arguably the world’s favorite beverage.

Weasel Brew

Many of the coffee farmers in Dak Lak and adjacent Lam Dong and Dak Nong provinces are from ethnic minority tribes. There are 54 separate groups throughout Vietnam, each with their peculiar dialects and cultural identities. Prominent near Buon Ma Thuot are the Ede, with more than 300,000 members. Among them is famed model H’hen Niê, a 2018 Miss Universe finalist who served as “media ambassador” for the coffee festival: She grew up in a coffee-farming family.

The World Coffee Museum opened in 2018 on a low hilltop in the heart of the city of Buôn Ma Thuột. Its architecture resembles a stylized series of Ede long houses. Aerial photo by Trung Nguyên Legend Group.

It could be that some of the Ede or other minority farmers were the first to discover what is known today as cà phê chồn, or “weasel coffee.” In fact, it should be credited to palm civets, not to their distant-relative weasels or minks. Regardless of the animal, the principle is the same: It’s shit. Really good shit.

Small, furry palm civets love the ripe red coffee cherries. (In Indonesia, where the beans are also cultivated, the animals are known as lawak.) As they eat, digestive enzymes partially ferment the fruit, removing the hull but leaving the excreted seed. Farmers gather the beans and thoroughly wash them before processing. The resulting coffee is rich and mellow, with notes of caramel and chocolate. It is outrageously expensive: US$3,000 will buy a one-kilogram bag of beans.

Rock ’n’ Roll

Kalfie Bredenkamp, the coffee lover, believes he can make Vietnamese cà phê the next big thing in his native South Africa. “The way they make it here (in Vietnam) breaks all the rules of what people say makes good coffee,” said Bredenkamp, 31. “It’s so strong. It’s rock ’n’ roll coffee. And I love that.”

Bredenkamp noted fundamental differences in size, taste, caffeine content and yield between the two families of beans. Now, he is buying whole beans and making his own blends of Robusta and Arabica by trial and error.

Coffee in the form of ripe cherries will be sorted, cleaned and laid to dry on mats. It may take a month of raking and hand-turning before they are ready for dry-milling. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson.

“Here, coffee is roasted heavy, almost like moer coffee in South Africa,” he said. “It was always the best.” In the Afrikaans language of his homeland, Bredenkamp explained, moer means “throwing a punch.” That’s not so different from the old chuckwagon coffee of the American West. Or from the punch it packs for the Westerner indulging in Vietnamese coffee for the first time.![]()

East-West News Service Contributor John Gottberg Anderson recently wrote about Tét, Vietnam’s lunar new year holiday and the Áo Dài, the elegant dress worn by Vietnamese women